When I heard about an art gallery of light fixtures, the first image I conjured in my mind was an IKEA lighting section filled with NÄVLINGE and SINNERLIG. “Electrifying Design: A Century of Lighting” felt like the nostalgic IKEA lighting section on steroids. The curators created both a visually stunning and intellectually enlightening experience for the viewer, guiding the viewer’s eye over everything from tube lights curled onto the floor of the space to massive multi-section chandeliers pulling attention to the gallery’s ceilings.

The exhibition was organized into three sections: Typologies, the Bulb and Quality of Light, each of which added a nuance to both the past and future of lighting that I would not have previously contemplated. The sections addressed an array of lighting typologies, new representations of the common light bulb and innovative ways artists have manipulated the quality of light. The artworks in this exhibition represented a century of light, including artworks from 1927, 1977, 2007 and beyond.

The first section, Typologies, highlighted how artists play with and challenge stylistic categorization. Many artists throughout time have resisted being creatively pigeonholed, whether it be genre-bending musicians or movement-defying painters. Lighting artists are no different. Experimentation was often the key to defying boundaries and expectations throughout history of art. An amazing example of this is the “Dear Ingo Hanging Light” by Ron Gilad — a spider-like and completely size-adjustable chandelier made from desk lamps. The artist is often described as walking the line between the abstract and the functional. Gilad’s work pushes us, as both artistic viewers and consumers, to question ideas of objecthood and function, especially when an ordinary, cheap desk lamp becomes extraordinary art in the form of an ostentatious chandelier.

Similarly, Erwan Bouroullec’s “Square Vase Table Lamp” (2001) recalled both a lighted cuboid tank and a flower vase for orchids. The title alone betrays the multiplicity of the object as both a vase and a lamp. In essence, it was a fiberglass cube with a fluorescent bulb illuminating some suspended pink orchids within the square. Bouroullec made two of the most commonplace objects into something futuristic and otherworldly through a genre-bending, experimental combination.

Not only was my understanding of lighting categories completely transformed in this exhibition, but my awareness of the parts of lighting was as well. The Bulb section made me incredibly aware of the light bulbs everywhere I passed. What color of light do they exude? What type of bulbs are they? What do bulbs look like when turned off? The bulb itself is what makes a light fixture functional, and in recognizing that pivotal role, some artists chose to illuminate the purity of the bulb, whereas others played with its “alchemy and potency of possibility,” as the wall label explained. Ettore Sottsass was one of the former, using a translucent layer to coat a curved tube light bulb, keeping the bulb in clear view for the user without a shade or decorations to obstruct it. Martine Bedin is one of the latter, as his “Super Lamp” exhibits the strange, nonfunctional playfulness one can achieve using the bulb. There is a certain wonder to this colorful lamp on wheels, and it brought an immediate smile to my face, which is an accurate way to describe the entirety of “Electrifying Design.” In the exhibition at large, the layered displays of light fixtures, primary blue and yellow walls and surprises around each corner made for a whimsical experience.

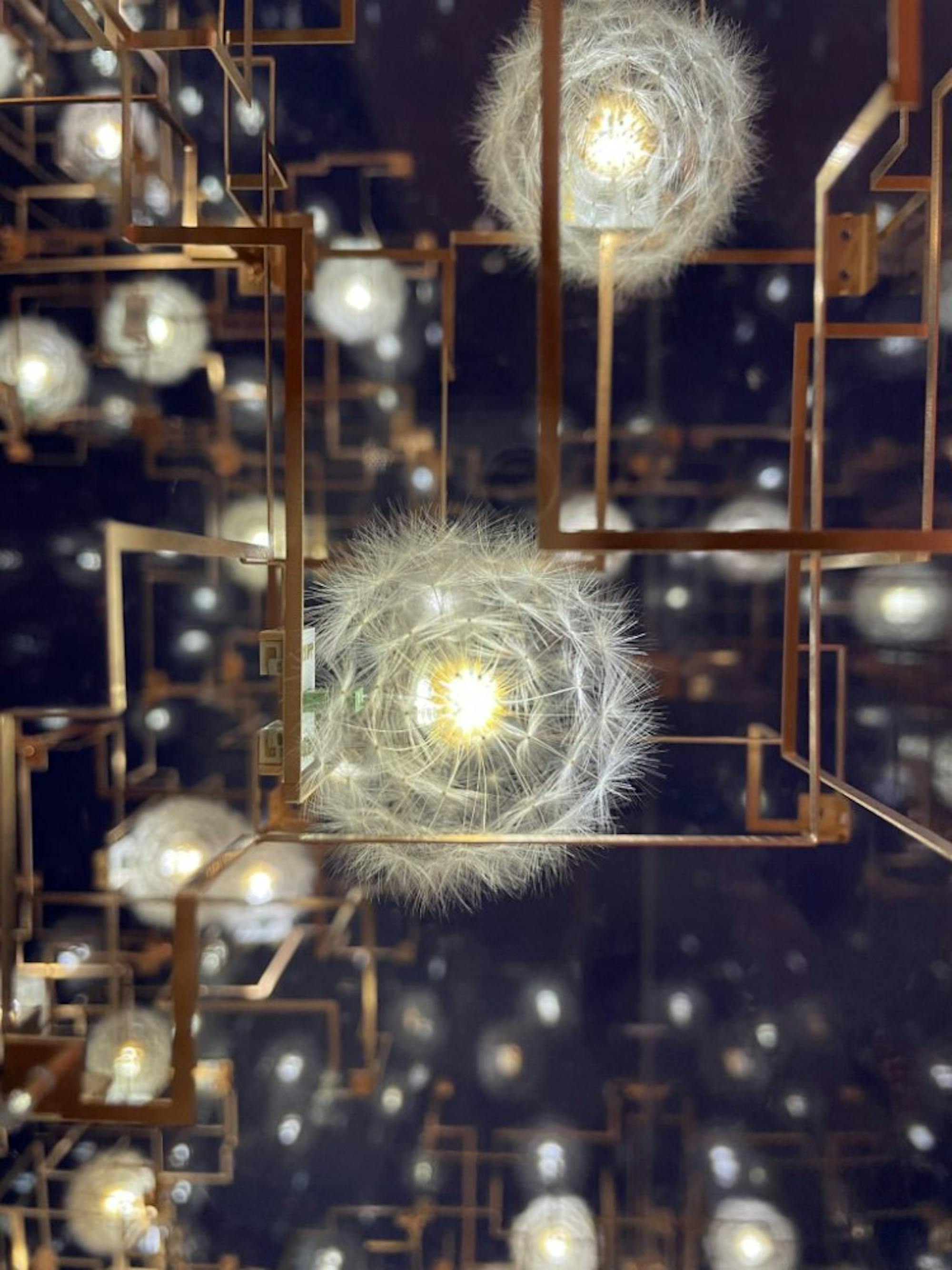

The joy of this exhibition made it feel as though the visitors had entered a world’s fair of light fixtures, with innovation around every corner. The final section, Quality of Light, was one of the most astonishing and eye-catching sections of the entire exhibition, and it was the perfect way to end this explorative journey. This section focused on some of the most dramatic and nonfunctional light fixtures and highlighted the way lighting can enchant, transform and emotionally stir the viewer. By this point in the exhibition, I was convinced of the way that lighting can be far more than a commonplace marking of humanity’s diurnal rhythms, but this final section truly cemented that idea. Each artwork created a very distinctive optical sensation, whether that be a physically immersive red shroud of light rings or a miniscule, elaborate rendering of lightened dandelions — the unnatural and the natural.

This exhibition addressed the ways in which light fixtures are both a modern necessity and an imagination-driven creative pursuit. Light itself is described in the exhibit as a “magical animator and activator of space that can transcend formal design.” If you want to transform your own understanding of lighting, I highly recommend you check out “Electrifying Design.” I was enlightened, literally and figuratively, by the entirety of my experience.