For the majority of our brief and largely uneventful time on this particular space rock, we human animals have believed that we are the pinnacle of evolution. We think we are the supreme beings; the crème de la crème of the gene pool. In recent years, we have begun to understand how flawed this perception is. On June 7, 2012, a truly remarkable event took place. A group of prominent neuroscientists gathered at the University of Cambridge to sign a proclamation declaring human and animal consciousness alike. Called the “Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness,” the document states:

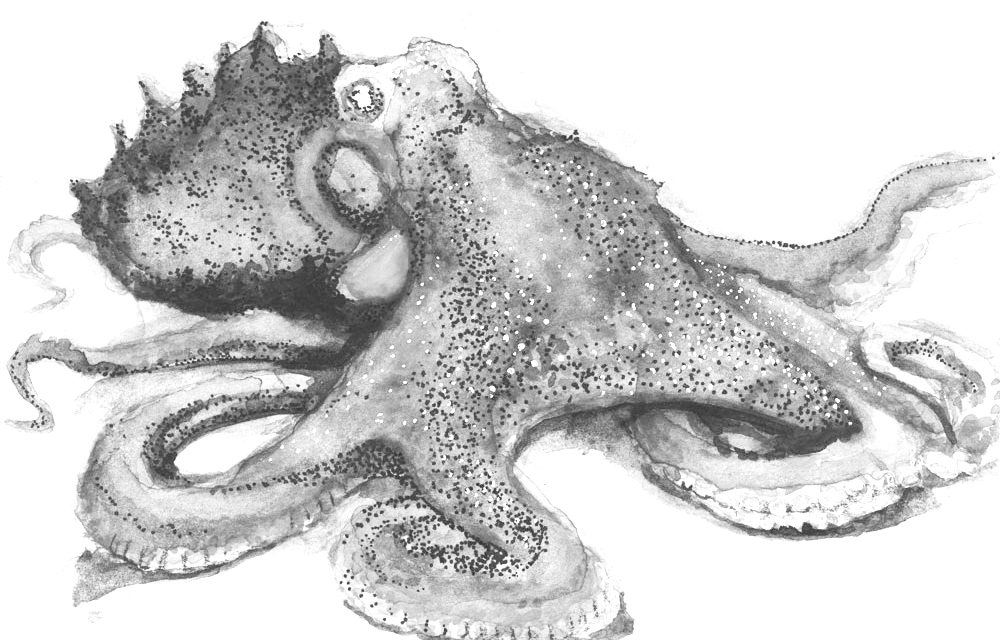

“We declare the following: ‘The absence of a neocortex does not appear to preclude an organism from experiencing affective states. Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviors. Consequently, the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures like octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.’”

This discovery has massive implications for the fields of science and philosophy. We must now begin to reevaluate our conception of consciousness and what it means to be conscious.

To begin this reevaluation, let us consider emotions. The concept of animal emotion goes back to at least Ancient Greek philosophy and was prominent in Charles Darwin’s works, most clearly in his 1872 book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. In modern times, emotions are considered to be an integral aspect of intelligence and, while intelligence and consciousness are different things, you can’t have one without the other. In the 20th century, physiologists recognized the significance of emotion to animal behavior.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Dr. [O.E.] Dror explains how the emotional state of animals was considered to be a source of noise in physiological experiments at that time, and researchers took steps to ensure that animals were calm before their experiments.” This proves that, even when we were doing experiments on animals, we still were aware of at least the presence of enough emotion to warrant calming them down. More recently, psychologist, psychobiologist and neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp (2004, 2005) has been conducting a research program in the subfield he calls “affective neuroscience,” which encompasses direct study of animal emotions. Over several decades, his work has elucidated the neuro- and moleculo-physiological bases of several “core emotional systems” including “seeking,” “fear,” “rage,” “lust,” “care,” “play” and “panic.” Panksepp argues that these are shared by all mammals and may be more widely shared among vertebrates.

Another interesting line of inquiry that is integral to what we believe it means to be conscious is self-awareness. Gordon Gallup Jr., an evolutionary psychologist, developed the mirror-mark test to analyze self-awareness. The test took chimpanzees that had extensive prior familiarity with mirrors, anesthetized them and marked their foreheads with a distinctive dye, or, in a control group, anesthetized them only. Upon waking, marked animals who were allowed to see themselves in a mirror touched their own foreheads in the region of the mark. The idea for the experiment came from observations well known to comparative psychologists that chimpanzees would, after a period of adjustment, use mirrors to inspect their own images. However, this test has been criticized due to the fact that it could be unfair to animals that relied much more heavily on other senses than sight, as well as animals such as dolphins that cannot physically touch their own foreheads.

Even more interesting, I think, is the bailout response test. Animals, primarily chimpanzees and dolphins, were placed in situations of cognitive uncertainty and, when given the “bailout” option, which allowed them to avoid making difficult decisions, would do so in a manner that was very similar to humans. According to observations from a 2006 study, “The fact that animals who have no bailout option and are thus forced to respond to the difficult comparisons do worse than those who have the bailout option but choose to respond to the test has been used to argue for some kind of higher-order self understanding.”

So where does that leave us? We have strong and growing evidence that animals experience this world, this face of time, through a similar lens as we do. They feel pain as we feel pain. Their experiences of love, laugh, play and fear are as powerful as ours . These findings should incite an ethical revolution in the treatment of non-human animals. As the beings that impact our environments the most, we must reconsider our role in the treatment of animals. The majority of literature on the experience of animals is based in pain and suffering due to our perception of animals as objects to be utilized in the service of our selfish goals. If we understand that animals experience the world in much the same way we do, we must change our behavior to respect that similarity, that closeness to nature that is implicit in our existence. No matter how much we like to imagine that we are separate from the environment, we are not. Reevaluating our relationship with all life on earth can begin with the understanding of what it means to be conscious, to experience existence and to be able to react to change over time.

Kagan Fletcher is a College freshman from Little Rock, Arkansas.

“This discovery has massive implications for the fields of science and philosophy. We must now begin to reevaluate our conception of consciousness and what it means to be conscious.”

What discovery do you speak of? You merely referenced some declaration by a group of neuroscientists.

This isn’t a discovery. Anybody with half a brain know that animals have emotions and intentional behavior. However, the fact that human beings have the capacity to discuss the ethical implications of this knowledge is evidence of our superiority. Lions don’t sit around and discuss the ethics of eating gazelles. Praying mantises don’t talk about the ethics of eating one’s mate.