After the College and Laney Graduate School announced a series of shutdowns and suspensions last Friday, many students and faculty demanded to know about the specific criteria used to determine how departments and programs were selected.

As the Wheel reported on Tuesday, College Dean Robin Forman based many of his decisions on talks he had with a committee – one that, until now, had remained relatively unknown to students.

Origins

The origins of the Faculty Financial Advisory Committee stretch back to late Fall 2007 under former College Dean Bobby Paul.

At a time when the financial markets started to collapse and university endowments across the United States were hit hard, Paul established a group of faculty and administrators to advise him, according to Micheal Giles, a professor of political science and the chairman of the Faculty Financial Advisory Committee since 2008.

In the spring of 2008, the group emerged as an official subcommittee of the Governance Committee consisting only of eight faculty members.Given the constant state of flux of the University’s finances, the committee met at least twice a month for the first two years, Giles said. During that time, the committee reduced funding for various institutes and programs in ways that had “minimal impact on the experience of students,” according to Giles.

There came a point, though, when members of the committee became concerned that the dean would request that certain programs be eliminated.

“When you’re confronted with the shortfalls that were being predicted, we realized that we could be asked at any moment, so we set about to school ourselves,” Giles said.

With permission from the dean and the provost, the committee acquired exhaustive documentation: department-planning materials, department self-evaluations, patterns of enrollment, course cross-listings with other departments, external reviews – everything, Forman remarked, just short of an individual’s salary.

The committee, then, set criteria and parameters for evaluating departments.

“Thinking in terms of scholarly distinction and potential for eminence of programs, how much does it take to move a program up? Some are more costly than other,” Giles said. “How distinguished is a department? What’s its role in the liberal arts? How essential is it? If it’s excised, can you still have a viable liberal arts program? Interdependence [with other departments] goes into that [criteria] as well.”

Giles also said that a key consideration was a department’s centrality in the liberal arts. Without mathematics, for example, physics and biology would be undermined.

- Members of the Committee (2012-2013)

- Keith Berland | Associate Professor, Physics

- Huw Davies | Professor, Chemistry

- Robin Forman | Dean of the College

- Michael Giles | Professor, Political Science

- Pam Hall | Associate Professor, Religion

- Stefan Lutz | Associate Professor, Chemistry

- Bobbi Patterson | Senior Lecturer, Religion

- Rick Rubinson | Associate Dean/Professor, Sociology

The Plan

In addition to the committee’s recommendations, Forman and other administrators had their own thoughts, according to Giles.

Once Forman finalized everything, he presented his plan to the committee, which approved the measures.

“This is a relative judgment,” Giles said. “We’re not saying we don’t value journalism, that we don’t value educational studies. What we’re saying is that when you think about the criteria, there are others that came out further up in the consensus of that judgment.”

Giles also noted that the decision was not an effort to “share the cuts equally,” but really to focus on where there was the possibility of pursuing “eminence.” In the same spirit, Forman has stressed the need for the University to “narrow its scope.”

Richard Rubinson, another member on the committee and an associate dean and professor in sociology, further elaborated, “We’ve collectively created this problem. When you think about the number of programs that have proliferated in the University in the last 20 years, something had to give. This is what happens when you have an unregulated spiral of expansion.”

Communication and Transparency

Back in 2008 when his colleagues asked how the situation was looking, Giles said he would always “lie” about how well everything was going.

“If people had known about the kinds of talks we were having, there would have been widespread panic. But nothing came of it,” Giles said. “Nothing we’ve ever talked about has been leaked to anyone.”

Hank Klibanoff, the director of the journalism program, said he disagrees with Giles’ thoughts on transparency.

“That’s the problem in a democracy,” he says. “You’re always going to be open to argument because you include people. I’d be sorry to hear if any institution that I’m part of decides that the people most affected by the decision can’t be part of the discussion because they might disagree and because they might become emotional.”

Giles said he understands the recent complaints about a lack of transparency, but does not think the issue is a one-way street.

“Some of that isn’t hearing,” he said. “I’ve been in meetings with chairs and directors, and I’ve heard [the deans] lay out these kinds of issues, and to think that there were going to be no consequences, no difficult decisions to be made downstream is just not hearing what’s being said.”

Giles also said departments have their chance to make cases for themselves.

Departments and programs are required to perform self-evaluations in which they write what they have accomplished, where they stand in their mission and what their plans are in the future.

“If you don’t think people are going to take those materials seriously, you need to think again,” he said. “So when you say, ‘I haven’t had a hearing,’ this is like ‘you’ve submitted briefs, but you just didn’t get oral arguments.'”

Moving Forward

Giles said he loses sleep over these kinds of decisions and wishes the communication process was clearer. On the flipside, he isn’t sure what the solution would be, fearing that too much transparency would damage the University.

“I’d rather take the heat for a lack of transparency than see the antagonism of ‘why this department and not that one’ that comes from open discussion,” he said.

Additionally, he stands by the plan as an important move for the University in achieving its ambitions and making diplomas for its graduates more valuable in the future.

Barbara Patterson, a senior lecturer of pedagogy and another member of the committee, said she is proud of the way the community came together during Monday’s discussion on the Emory Quadrangle and believes in an evolving process.

“When we all keep working together to make the process stronger and more transparent, we are changing things,” she said. “I know that Dean Forman has said that the decisions are the decisions, but things aren’t over. The processes aren’t over because when the process dies, the community dies.”

– By Evan Mah

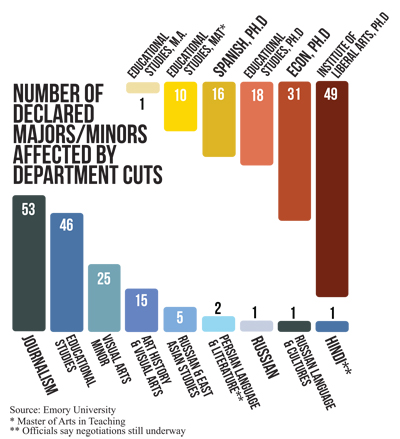

Correction (12:19 p.m.): The chart has been updated to show declared majors/minors affected by departmental changes. This chart does not show the number of students taking classes in these departments. The original chart said “affected students.”

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.

Dean Forman clarified during his presentation to the SGA on Monday September 17th that there was no representation from any of the programs/departments being cut on the Faculty Financial Advisory Committee.

So basically, Giles is saying “We intentionally didn’t tell people that we were making cuts because it would have gotten people to panic. But the affected departments are to blame for not hearing us properly.” What an idiot.

Also, it seems like your numbers in that chart lowball the number of students that are actually affected. You should have used the total number of major and non-major students in each department to show the true scope of those programs. Saying 53 journalism students are affected doesn’t really do justice to the true size of the department in that it actually serves more than twice that number of kids across the college (160).

Paul, thank you for your comment. We are working to get numbers on the total number of non-majors in each department.

What source provided the graph at the top of the page? It is entirely misleading.

Let’s be honest: there was never any real evaluation here: there were adminstrative motives behind the departments that were cut. Look at graduate econ. Obviously it was a program on the rise and definitely wasn’t underperforming. But Emory knew that cutting it would be detrimental to the undergrad econ department, which it wants because then more students would enroll in the b-school instead. Emory doesn’t want public discussion of that, because god forbid the people paying $45k a year in tuition demand that they have choices. But of course, the school that is willing to cheat to boost rankings is also willing to fuck with your education to do the same, even if it’s just an arbitrary spot on a list. Forman is the front man here, but this is clearly about more than just reallocation within the liberal arts, and those at the top of the administration that are behind all of this need to be held accountable.

If the Econ department were to suddenly disappear, what makes you think prospective Econ undergrads wouldn’t major in, say, Applied Mathematics instead? In my time at Emory, I knew plenty of Econ majors who had absolutely no interest in Goizueta, and I doubt that would change if the Econ department were blown up. Goizueta has a limited number of spots as it is and the undergrad gunners of the university already apply to it in droves. In other words, they wouldn’t be able to absorb the Econ department and, anyway, the achievement-oriented kids are already choosing Goizueta over Econ because they’re into rankings. An increased applicant pool doesn’t help them in any way. Goizueta’s rankings were COMPLETELY unaffected by the recent USNWR scandal so please don’t include it in your paranoia.

“How distinguished is a department? What’s its role in the liberal arts? How essential is it? If it’s excised, can you still have a viable liberal arts program? Interdependence [with other departments] goes into that [criteria] as well.”

– If I had to give a brief summary of the ILA’s role at Emory, that was it. It is one of the most distinguished, most essential (in terms of its value to the most departments), and unquestionably the most interdependent department at Emory. Clearly these criteria were by no means the basis for the Committee’s decision.

Further, Gile’s admission that he would “rather take the heat for a lack of transparency than see the antagonism of ‘why this department and not that one’ that comes from open discussion,” confirms suspicions that the rationale behind these choices is deeply flawed and could not survive an open debate.

I have never been more embarrassed to be affiliated with this institution.

I would also like to note that the graph at the top of the article is mislabeled. While I imagine its figures reflect students enrolled in each of the listed majors, it in no way indicates the number of students “affected” by this decision. It affects any student wishing to learn Russian or take a drawing class, for example. Emory University is weaker at an institutional level for the loss of the numerous classes associated with each of the “affected” departments.

To the Emory Community:

A total lack of transparency and objective criteria leaves the Emory administration open to serious allegations. I believe the burden of proof is now on the administration to show that the process of cutting departments and programs was NOT corrupted by favoritism, personal vendetta, money changing hands, backroom deals, etc.

An open process would have relieved all of these misgivings. As it stands now, there is no way for any department to be sure it isn’t NEXT. Surely a math professor could have figured out an open process with objective criteria. Department reports filed for the purpose of evaluation are surely not the same as reports filed to justify your very existence. Departments would have written such a report very differently, had they known.

We all understand that they may not be enough resources to go around, and that somebody may need to be pitched out of the lifeboat for the rest to survive. If your must, rank order all the departments by some objective criteria, and start pitching the weak ones overboard! But let’s be open and honest about it.

“‘If you don’t think people are going to take [self-evaluation] materials seriously, you need to think again,’ [Giles] said. ‘So when you say, “I haven’t had a hearing,” this is like “you’ve submitted briefs, but you just didn’t get oral arguments.””

The analogy of a trial is misleading and self-serving. Since the whole project was a secret, as Prof. Giles says, then faculty clearly thought they were submitting “briefs” for a different case than the one that was actually being tried. So we’re back to the lack of transparency argument: we couldn’t tell anyone what was going on, because then they would have known what was going on, but they should have known what was going on anyway so it’s their fault they didn’t know.

Giles’ logic makes perfect sense. If every department were to be on this committee, then it would instantly become Balkanized. No department would willingly sacrifice itself and, eventually, they may even form political alliances for self-preservation. Instead, they chose 8 professors who they thought would be objective.

And yes, of course they chose professors from departments that weren’t in danger. That way, the administration knew in advance that the professors would be impartial. If their own departments were safe, they had no reason NOT TO MAKE AN OBJECTIVE DECISION.

The only people squealing are liberal arts purists who think every major should be retained because of because. I’d like to see which departments the naysayers would choose to cut if they were faced with a similar decision.

The real reason people are mad isn’t “transparency” — it’s bruised egos over the actual results. Deal with it.

Thanks for your enlightening response, Dean Forman.

I think you’re missing the point here. What’s outrageous isn’t so much that the departments in danger of being eliminated weren’t on the faculty committee, it’s that the committee was never open about the whole process being about killing departments to begin with. The departments that got the axe feel like they never had their voice heard because they never knew they were in danger of outright elimination.

You also can’t just dismiss the transparency argument because you assume that there was nothing hindering the committee from making an objective decision. Those faculty members are still subject to internal politics that keep them from being truly independent of Dean Forman and the administration. So if Forman tells them “you’re free to make your own calls, but just so you know, we can see how our criteria would fit departments X and Y”, then the committee is obviously going to appease that. So where’s the window that allows everyone to see not just why cutting A is better than cutting B, but also why cutting A or B to reallocate their money is better than the status quo? Yes, that wouldn’t stop people from being butthurt if their departments get cut, but at least everyone else would have the information to judge if the cuts were good for the university as a whole. Sadly we haven’t been given that information, and that rightly has stirred up questions about what Emory is trying to hide.

So what Giles says about how he’d rather you not know about the decision process as opposed to letting the departments argue out their case is not just appallingly wrong, but it’s also a false way of framing the issue.

Dr. Forman,

No one is “feigning” anything. The reason people are upset is not only due to the lack of transparency, but also the total absence of planning beyond the moment of the announcement, an utter disregard for the students involved (really, a sense of shock that students might be upset that their departments no longer exist), and an obvious attempt to pit department against department and instil an atmosphere of fear and suspicion throughout the entirety of the Emory community.

Exactly! This has nothing to do with flagrant disregard of faculty governance norms, breach of contract laws, or terminations that disproportionately effect women, international students, and people of color. It’s actually all about “egos” and we should just “deal with it.” This is exactly the right attitude to take toward fiat and opaque exercises of authority, and I’m just so glad we have a Political Science professor anointing your stance of passivity as the only “reasonable” way to look at things. Silly people, whining about getting fired.

So now cutting Econ PhDs, journalism, and visual arts somehow disproportionately affects people of color? Where in the world did that one come from?

All of these replies completely miss the point. If Forman had somehow done all you are demanding — if he had made this a huge, messy, public affair with department heads in open contention for their jobs that ultimately resulted in departments being cut anyway, would the people posting these asinine comments be any less outrage? The answer is no. Of course not. I don’t see any endgame here that leaves departments like visual arts and journalism intact, let alone tiny PhD/Grad programs like econ and educational studies.

We would be in exactly the same situation we are now, except the faculty would have had an even WORSE taste in their mouths after being turned on each other for the sake of funding and students would be even MORE outraged because they’d be forced to take sides as well.

Budget cutting is not a wholly participatory activity. There are always going to be losers. If Emory had fired a large chunk of its secretarial staff, many of whom are African-American Atlanta natives, people would be up-in-arms about THAT and not the professors.

I admire Forman for having the courage to make a necessary, if unpopular, decision.

“Where in the world did that come from?” From demographic data directly available off Emory’s own websites. Overall, minorities made up 14.8% of full-time faculty in 2009, but 45.5% DES faculty, 40% of Russian and East Asian Languages and Cultures faculty, 47.8% of Spanish and Portuguese faculty, 25% of Physical Education faculty, and 20% of Economics faculty. These 5 departments are within the top 9 departments in terms of minority representation of the University’s 36 departments in the College of Arts and Sciences: pp. 16-20,

http://provost.emory.edu/documents/community/cd_profile_volume2.pdf

Overall, women made up 40% of Emory’s full-time faculty in 2009,

but 100% of Journalism faculty, 80% of Russian and East Asian

Languages and Cultures faculty, 60% of Spanish and Portuguese faculty,

55% of DES faculty, 50% of Visual Arts faculty, and 50% of Physical

Education faculty. These 6 departments are within the top 15

departments in terms of representation of women: pp. 25-29,

http://provost.emory.edu/documents/community/cd_profile_volume2.pdf

I’m glad to see, though, that you think that the more obvious place where Emory would have a large African American andstaff representation would be its “secretarial staff.”

“Wow. Where did that come from?” The demographic data on the cuts is available online from Emory sources.

Overall, minorities made up 14.8% of full-time faculty in 2009, but 45.5% DES faculty, 40% of Russian and East Asian Languages and Cultures faculty, 47.8% of Spanish and Portuguese faculty, 25% of Physical Education faculty, and 20% of Economics faculty. These 5 departments are within the top 9 departments in terms of minority representation of the University’s 36 departments in the College of Arts and Sciences: pp. 16-20, http://provost.emory.edu/documents/community/cd_profile_volume2.pdf

As for women, overall, they made up 40% of Emory’s full-time faculty in 2009, but 100% of Journalism faculty, 80% of Russian and East Asian Languages and Cultures faculty, 60% of Spanish and Portuguese faculty, 55% of DES faculty, 50% of Visual Arts faculty, and 50% of Physical Education faculty. These 6 departments are within the top 15 departments in terms of representation of women: pp. 25-29, http://provost.emory.edu/documents/community/cd_profile_volume2.pdf

What does it say about you that the place you think it’d be more likely to find African-American as Emory is the school’s “secretarial staff”?

Maybe you should also read about the history of the DES, its involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and its ongoing engagement with local schools. http://des.emory.edu/home/about/history.html

The demographic data on the cuts is available online from Emory sources.

Overall, minorities made up 14.8% of full-time faculty in 2009, but 45.5% DES faculty, 40% of Russian and East Asian Languages and Cultures faculty, 47.8% of Spanish and Portuguese faculty, 25% of Physical Education faculty, and 20% of Economics faculty. These 5 departments are within the top 9 departments in terms of minority representation of the University’s 36 departments in the College of Arts and Sciences.

As for women, overall, they made up 40% of Emory’s full-time faculty in 2009, but 100% of Journalism faculty, 80% of Russian and East Asian Languages and Cultures faculty, 60% of Spanish and Portuguese faculty, 55% of DES faculty, 50% of Visual Arts faculty, and 50% of Physical Education faculty. These 6 departments are within the top 15 departments in terms of representation of women.

You write: “If Emory had fired a large chunk of its secretarial staff, many of whom are African-American Atlanta natives, people would be up-in-arms about THAT and not the professors.”

Administrative staff ARE being terminated because of these cuts – nearly half of the firings are for staff. As for concrete connections to the Atlanta community, maybe you should also read about the history of the DES, its involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and its ongoing engagement with local schools through the TITUS program.

But here’s the real question: What does it say about YOU that the place you think you’d be most likely to find African-Americans at Emory is the school’s “secretarial staff”?

A quick look at your “statistics” and they already fail the sniff test. Women are 100% of full time journalism faculty? So I guess the director of the program, Hank Klibanoff, doesn’t exist? Women aren’t even 100% of the department’s TEMPORARY faculty. I have no idea where you’re pulling your sources, but the department’s own homepage contradicts you.

It’s completely disingenuous to throw the foreign languages departments into your argument. You’re essentially arguing that the Spanish department shouldn’t be cut because there are Spanish people in it. Redundancy? Yeah. I think so. And anyway, of the Spanish department has 16 full time faculty members, 7 of which are men. Since when is cutting a department with two more women than men a disservice to womankind? You intentionally use the percentages to make it seem like there are many more women within the department in real terms. Way to mislead.

Since when did I say that it was the place you’d “most likely” find African-Americans? All I said was that a large portion of them were black Atlanta natives, which is true. There was no racist intention there at all — simply a statement of fact. Thanks for outing yourself as a race-baiter though. It suits you.

You can find all this data on the provost’s website – the report is entitled Community and Diversity (a PDF) and this comment section will not allow embedded links to it. If you care to read carefully (heaven forfend) you will see on both that website and in what I said above that those statistics are from 2009, which was the last time such data was collected.

I take it you have no particular thoughts on the closing of the DES – with all it’s history and it’s engagement with local Atlanta schools. And you’re not acknowledging the firing of the very staff who you invoked previously. You may also not be aware that the Department of Spanish and Portuguese includes people of many ethnicities hailing from multiple continents – to refer to them all as “Spanish People” is, well, interesting.

At which I think it’s time for me to stop feeding the trolls.

I’m new to the thread, but I couldn’t let this go by. So, we shouldn’t mention the fact that a large number of Hispanic people’s jobs are affected, simply because they are teaching Spanish? I suppose when Hispanic people teach Spanish, they become redundant, just like how when Black people teach African-American studies, their Blackness is no longer relevant? It’s a good thing we have more women than men in the Gender Studies department – that means we can cut their department next, because they’re redundant, right?

And if you think race-baiting is when you simply acknowledge the facts of the diverse makeup of the faculty, and provide that information openly for other people interested in the cuts issue, you have a serious problem. Do you suggest we suppress the information, or ignore it, as the administration appears to have done? If you don’t think that information is relevant, fine. That doesn’t mean you should accuse other people of race-baiting simply because being exposed to the information makes you uncomfortable.

No you see what our friend is saying is that we should be addressing the racial status of people only when we find minorities in places where you wouldn’t expect them – you know, beyond doing *obvious* stuff like teaching Spanish or working as “secretarial staff.” …

Thanks for this fine reporting. Many alums and current students were wondering what led to this recent announcement. And thank you Prof. Giles for your candor. As a former student of the journalism department, this news saddened me. I was proud at the level of training I received from the department, and many classmates from those years later became colleagues at major newspapers. I’m guessing the students who reported and wrote this story also benefited from that kind of training. -alum, class of 2003

Sorry guys, but democracy isn’t the best system of governance for all things.

So I take it you have a Political Science Degree. Or, as the university will soon be re-branding the Department, in Human Resources.

If Evan Mah’s reporting is true and accurate, this article all by itself makes the case for the necessity of critical journalism at Emory. What we learn from and about Michael Giles is astonishing:

* That Giles consistently lied about the nature of the Financial Advisory Committee’s work;

* That Giles’ committee was authorized to collect departmental documentation prepared for various routine purposes, in order to secretly evaluate the merits of departments’ and programs’ very existence at Emory;

* That Giles knowingly suppressed democratic processes in what he knew was work with far-reaching consequences ( “I’d rather take the heat for a lack of transparency than see the antagonism…that comes from open discussion”).

What Mah appears to have uncovered is basically a junta operating from inside the Governance Committee, secretly trying departments and programs in absentia for elimination. The entire Emory community should be deeply troubled that for over four years Giles and his committee acted so dutifully to undermine shared governance and open debate.

Mah does not mention it, but it’s worth recalling that while Giles’ “advisory” committee was conducting its hatchet work, Giles’ power extended even further. He led the search committee that chose Robin Forman as Bobby Paul’s successor.

I am so heartened by Professor Giles’ commitment to an ethos of transparency and participatory democracy. Against the backdrop of a university that expresses its “commitment” to the liberal arts by gutting the programs that sustain it, having a department of Political Science staffed by back-room wheeler-dealers and apparatchiks who would rather not be bothered by transparency when assessing the employment value of their colleagues seems perfectly fitting. Accountability is just so tacky, isn’t it?