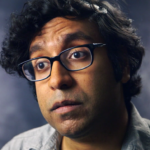

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

When people think of art, stand-up comedy typically isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. But writing and performing comedy, like painting a mural or performing a choreographed dance, is a work of art.

Like painters, comics rely on the familiarity or absurdity of images to tell a story. Professional comics do this regularly through language instead of visuals, and thus, not unlike dancers, become familiar with their own rhythms and how to deliver a routine in an honest and nuanced way. When comedy is “bad” or ineffective, it’s usually empty dick jokes, or worse, jokes at the expense of someone’s humanity. But when comedy excels, it has the power to affirm people’s humanity and to make people pause, reflect and, most importantly, laugh.

Hari Kondabolu, a Brooklyn, N.Y.-based stand-up comic, is a champion of the kind of comedy that soars. His work as a political correspondent and writer for “Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell” and his 2017 Netflix special, “Hari Kondabolu: Warn Your Relatives,” exemplify his thoughtful approach to tackling social issues like racism, sexism and homophobia.

The Wheel sat down with Kondabolu to discuss his show on March 1 at Center Stage Theater. This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Adesola Thomas, The Emory Wheel: What is something people should know about your comedy, and something they should anticipate at your Center Stage show?

Hari Kondabolu: I like to talk about big issues. People call it political, but I think it is operational. I think a lot about racism, sexism and homophobia. It’s something I see often in media and in the day-to-day world, so I like talking about those things. I usually make people uncomfortable and I like to get a laugh out of that. It’s usually about weaving in and out of discomfort and trying to find a laugh when it is a bit too much. I like that. I like the idea of challenging people and still making them laugh. That’s my job as a comedian. It’s not the easiest way to do it, but that’s how I do it.

TEW: I’ve found comedy to be an important catharsis, especially during politically tumultuous times. Do you feel especially responsible when handling political messages in your comedy? Do you look to other comics when things are difficult?

HK: I won’t speak for other comics. But personally, I have a sense of responsibility to not make things worse and to do my best not to make people’s lives worse. So if I am going to be talking about racism, I am not going to be homophobic while I do it. I am not going to bring myself up by putting others down. It’s hard, but that’s part of my responsibility. People are in pain in a lot of different ways, and when they come to comedy shows after a long week, they just need to laugh. The people that I think need to laugh the most are people who are dealing with depression. It’s people who — whether you’re a woman, a member of the LGBTQ+ community, a person of color — get to laugh about the things that hurt them. I want to create space for people to laugh. In that way, it is cathartic.

In terms of comedians I watch, W. Kamau Bell is still one of my best friends. He’s someone who has managed to do the hard work in a mainstream way and challenge a lot of assumptions. That keeps me going and reminds me that my work can have the ability to reach people.

TEW: You’ve made jokes about how your parents are still waiting for you to sit down and take the LSAT. How do you reconcile the pressure you feel to be pre-professional? Do you have advice for other children of immigrants who struggle with honoring their own dreams versus the dreams of their parents?

HK: First, I should say that my mom is very positive about what I do and pushes me. I do not think this was her goal for me, to be a comedian. At the same time, she is proud of me and my success, and so is my father. That is a pretty big deal. I do not think they’re waiting for the LSAT any longer. But I think there was some truth in that at that [time].

There is also the added pressure of cultural expectations. Beyond cultural expectations, the “we sacrificed everything; please make the most out of what we sacrificed,” makes for a lot of pressure. … At the end of the day, you have to be happy with your life. No one can live your life for you. Even though I do something that isn’t professional in the way my parents wanted, it’s a profession. [Although] it’s not a doctor or a lawyer, I still think of my parents’ work ethic when I approach this job. I always think of my folks. They worked seven days a week; they’re constantly pushing themselves to their limits. If they can do that with jobs that are significantly harder, why can’t I do that with this?

I did not jump into this. I did not go headfirst without thinking about it. It may be less romantic, but I got my master’s [degree] before doing this. I was doing stand-up because I love doing stand-up, but I was doing it without the goal of it being a professional pursuit. This happened because I was good. You can take a risk on something you care about for a few years of your life. Some people have safety nets and some people don’t, and I think it’s much harder to make that decision [without one]. But taking a couple of years to pursue what you want and see what happens is not the worst thing in the world. If you love something enough, you keep doing it. If I didn’t do stand-up professionally, I would still do something creatively. If you love something, you make time to do it.

TEW: What’s the last thing that made you laugh really hard?

HK: Whenever I hang out with my friends, W. Kamau Bell and Dwight Kennedy, I always laugh a lot. When you’re a comedian, you are always competing for the best laugh with friends. Laughing with friends is always going to be superior to any laugh you get at a comedy club. When you are making jokes with your friends, there is no explanation; they know you already.

TEW: Is there anything you would tell your 21-year-old self about life, adulthood or comedy?

HK: It’s not a linear path. It does not go straight up. It comes in waves. You will find success earlier, and then it will dip. You are slowly progressing, but it doesn’t feel like it because there are lots of ups and downs. I didn’t realize what I was giving up when I embarked upon this. I gave up time with friends and family because I was traveling. I missed lots of important occasions. I lost stability. I lost sleep. These are all things that are difficult and have [an] impact on your life, and, if I had been told this [when I was] 20-something, I don’t know if I would have agreed. There are lots of things you do not understand until you experience [them].

TEW: What has comedy taught you?

HK: Comedy has taught me that honesty is important. My favorite comics are incredibly honest. And if you’re honest about the truth that you believe, whether or not people agree with you, they will respect it. Comedy certainly taught me to listen to people. Those early days were some of the first times I heard people talk about their experiences. They were not like me. They were not always college-educated. For me, as open-minded as I thought I was at 22, it stretched when I started doing comedy. It taught me to listen and appreciate people’s stories. It taught me to be less judgemental.

A&E Editor | adesola.thomas@emory.edu

Adesola Thomas (20C) is from Hampton, Ga., a place she refers to as "the land of cow pastures." She is a double major in political science and English. She enjoys cooking, long scenic walks and looking at pictures of black labs on the internet. The first song Adesola ever learned how to rap all the way through was Kanye West's "Herd Em' Say" which she now feels mildly conflicted about. Adesola brings up Greta Gerwig's "Lady Bird" at least once a day and wrote every one of her college admissions essays about the social impact of "Saturday Night Live." She can hide up to twelve pencils in her afro and enjoys writing about people and art.