It’s close to midnight, and you’re in your car by yourself. You’ve been driving along an interstate highway for God knows how many hours now. You haven’t seen a single soul for the last hundred miles. You look outside for something, anything, other than the cement under your tires, but the night is all that surrounds you. Slowly, your muscles adapt to the twists and turns and your mind slips away. You forget where you are, where you’re going — but you remember where you want to be.

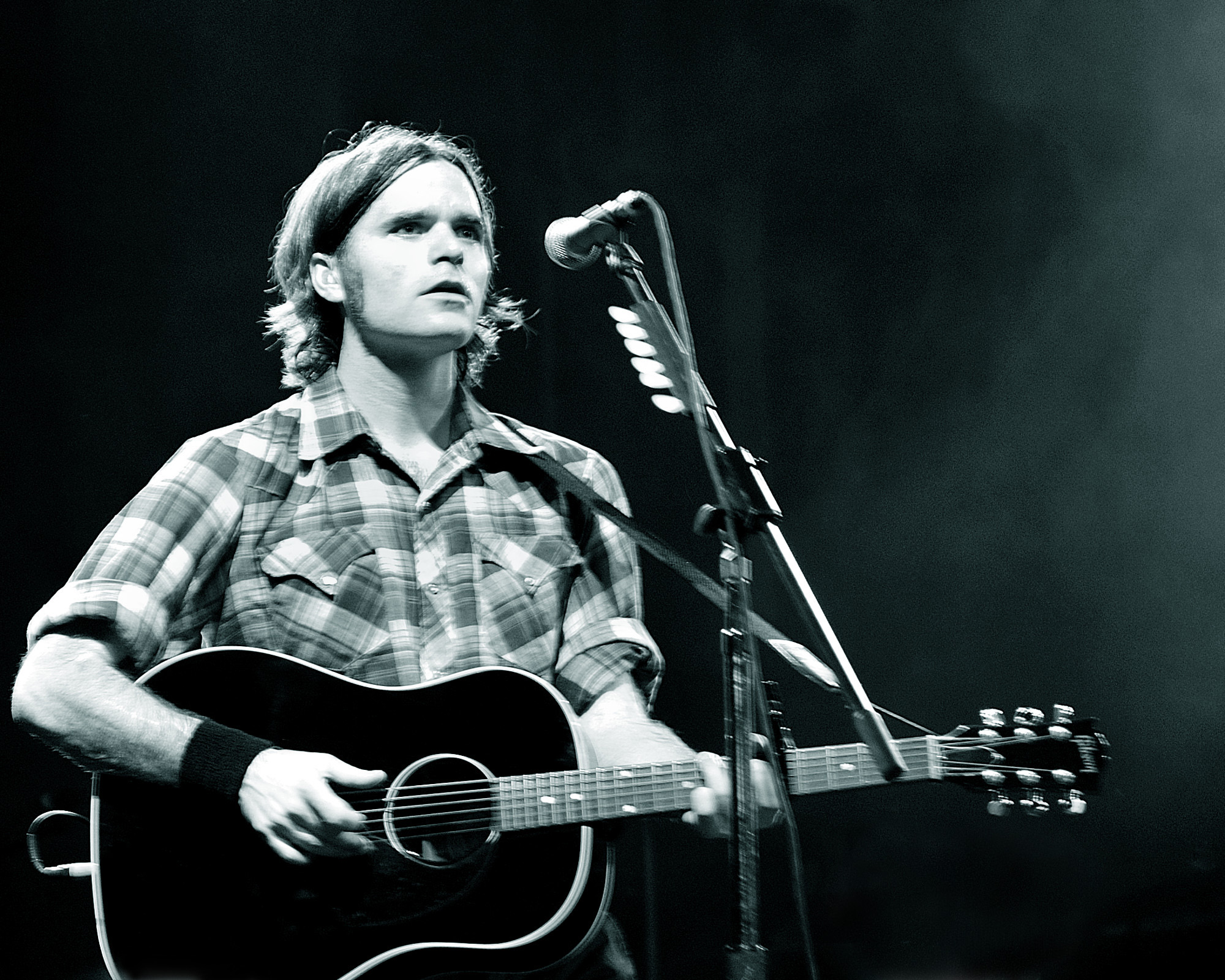

Road trips have a strange place in the human psyche. While in transit, removed from the goings-on of everyday life, we’re forced to pay attention to the only thing present: ourselves. Some of the most well-received musical releases of all time have used the highway as a setting (think Highway 61 Revisited, “Thunder Road”). And in 2003, indie darling Ben Gibbard and his band Death Cab for Cutie took inspiration from that setting to create undoubtedly one of the best albums of the decade.

Transatlanticism opens with the sound of an idling engine and cars rushing by in the background. The mind scrambles to identify the droning, which morphs into a meditative, peaceful sound, the kind that lulls you into your inner self. The noise fades as two-chord bursts guitar crescendo in, contrasting against the calm, but it’s already begun the process of engaging the listener.

The meditation begins, fittingly, with a song titled “The New Year” — a description of a supposedly celebratory scene that is only a circumstance that forces Gibbard to realize how little he’s truly changed, and confront the problems he simply can’t resolve. Yet the album’s main theme is only clarified in the last verse, when Gibbard wishes that “the world was flat like the old days/Then I could travel just by folding a map/No more airplanes, or speed trains, or freeways/There’d be no distance that could hold us back.”

Transatlanticism is essentially an album about the inescapable frailty of relationships, love and loss; much of the content is focused on the latter. “Title and Registration” mourns a faded love shoved back into the forefront of Gibbard’s mind by a picture hidden in the glove compartment, a “souvenir from better times.” The song acknowledges how such reminders can exorcise emotions that seemed long gone, as if they were never there.

“The Sound of Settling” is an all-too-upbeat, tongue-in-cheek look at shying away from love: how succumbing to that tongue-tying, paralyzing fear of being unable to say the right thing and rejecting romantic instinct can lead to a life filled with regret. “Tiny Vessels,” on the other hand, is a confession about a relationship completely driven by lust. It’s a low point for the album: Gibbard doesn’t even pretend as though he confused physical attraction with true attachment when he softly sings “This is the moment that you know/That you told you loved her but you don’t.” But for all the heartbreaks on this album, hope manages to gleam through. “Passenger Seat” is to me the most moving of these instances. It’s a quiet, open ballad, about the simple pleasure of spending time with the one you love as they drive you home, featuring Gibbard’s voice accompanied by a peaceful, resonant piano and wide, open synth pads rolling in the background.

Ultimately, Transatlanticism is an album that’s rightly earned a reputation for providing a lyrical, emotional weight mirrored in songwriting. This is the culmination of a craft perfected after years of work by Gibbard and Co. It’s an album that stays with you long after it ends: when the idling of the engine returns for a few breathless moments, as if the music never happened, and it’s just you and the road.

Grade: 5/5

Associate Editor | devin.bog@emory.edu

Devin Bog (20C) is from Fremont, Calif., majoring in biology and political science. He loves music, learning new things and the natural light on the main floor of Atwood Atwood Chemistry Center. Bog previously served as Arts & Entertainment editor.