Mindfulness is the prevailing self-help fad, designed to promote heightened, peaceful awareness through meditation and breathing exercises. It teaches us to manage stress by rethinking our circumstances.

But worldwide, mindfulness has become simplified, despiritualized and Westernized. It is, in San Francisco State University (Calif.) Professor of Management Ronald Purser’s words, the $1.1 billion buzzword of the wellness industry. While Westernized mindfulness remains an effective therapeutic tool, its advertisement disrespects the religious roots of mindfulness and neglects greater systemic issues like socioeconomic inequality and corrupt government policies.

Emerging from the Buddhist Vipassana tradition of meditation, the current form of mindfulness bears little resemblance to such roots. One of Buddhism’s four noble truths is the cessation of suffering: the liberation of the self from attachment and subsequent embarkation toward spiritual enlightenment. The goal of Vipassana practice is the practitioner’s detachment from desire and exploration of the relationship between change, reality and the self. Where modern mindfulness preaches the importance of finely attuning our senses to our environment, Buddhist texts never mention this idea. Modern mindfulness disrespects the centuries-old practices that monks spend their entire lives perfecting. Generations of tradition are reduced to “breathe, and all your problems will temporarily subside.”

Mindfulness does have scientific research to back it up and an abundant amount of benefits. It promotes peace of mind, decreases risk of heart disease by lowering blood pressure, reduces psychological pain and slows aging. It is beneficial in reminding us to remember the present moment and reflect on the impermanence of life so we can better appreciate reality. It encourages positivity in the face of adversity. Research has even suggested that mindfulness can aid in anger management, replacing vengeful thinking with increased compassion and understanding. As someone who practices mindfulness, I can attest to its de-stressing, calming and anger management properties. Mindfulness can alleviate anxiety and stress. But all its impacts are only temporary if you do not stop to examine the factors you are trying to fix in the first place. You will still find yourself treating the symptoms rather than the disease.

A positive mentality can only carry us so far. While it’s a crucial and necessary skill to develop, an excess of positivity poses a danger. It also remains a gross oversimplification of the sati Buddhist practice and distracts us from pressing, systemic socioeconomic issues. The power of positive thinking cannot put food on a family’s table. Mindfulness is for the elite: mindfulness classes and products are overpriced, which prevents those most in need from accessing these services. People facing systemic issues likely are not spending money on experiencing mindfulness workshops or reminding themselves to release their thoughts into the air like balloons and simply forget about their difficulties. Ecuadorian parents who have lost their jobs do not want to be told to just breathe and find change within. Mindfulness ignores deeper problems. Losing a job or losing a home is not just a state of mind that can be fixed through mindfulness.

Mindfulness itself is unproblematic, but the way in which companies are abusing it is problematic.

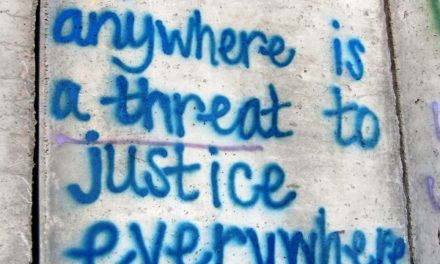

The high levels of stress and anxiety surrounding our lives today give rise to the power of mindfulness. Its integration into the wellness industry makes it the prime and novel “product” that businesses are now offering. Mindfulness courses and studios are popping up everywhere. Companies promote mindfulness as a way to show they care about their workers — “Search inside yourself,” said Chade-Meng Tan, Google’s former in-house mindfulness guru, “for there, not in corporate culture — lies the source of your problems.” Company-sponsored mindfulness forces individuals to take sole responsibility; it is part of a greater trend in individualizing societal problems. It allows companies to shirk from their liability and expect employees to return as well-rested dutiful workers. Propagating mindfulness to be self-centered deflects from building a community to actively create meaningful change.

Without understanding the roots of our problems, mindfulness becomes impermanent self-pacification. This is not about condemning mindfulness as a coping mechanism — it can work wonders in that regard. But we must be wary of its predisposition to self-absorption; if we divert our attention from deeper social problems, our unhappiness and dissatisfaction with life will only continue.

People have a right to know what true mindfulness is. If the term is to be used to market a new way of thinking, companies should make explicit its differences from traditional Buddhist ideology. It is not a panacea. It should not be so easily secularized to fit Western needs.

Maybe give mindfulness a try. But don’t sink too far into it that you forget to reflect on where your stress stems from.

Sophia Ling (24C) is from Carmel, Indiana.

Sophia Ling (she/her) (24C) is from Carmel, Indiana and double majoring in Political Science and Sociology. She wrote for the Current in Carmel. She also loves playing guitar and piano, cooking and swimming. In her free time, she learns new card tricks and practices typing faster.