THE MOST MASSIVE SPOILERS BELOW

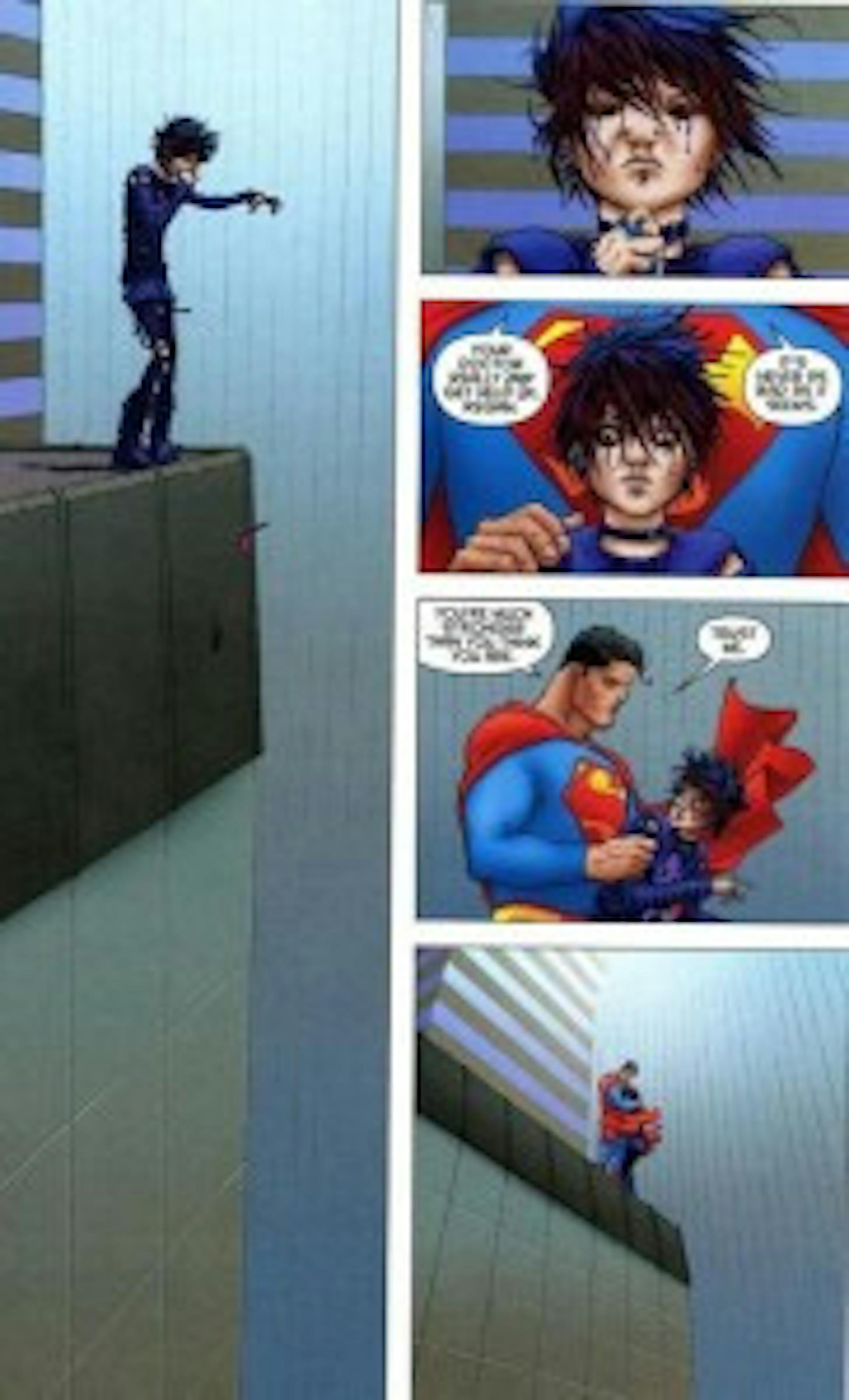

The world needs a Superman.

There’s something immensely comforting about the Superman fantasy. He’s the best of us, of course. He was raised in Kansas and imparted with the values to do good, no matter the cost. But he’s something more as well. He’s something greater — someone who would save people without selfishness. He’s what we aspire to be — someone with the ability and the willingness to be the ultimate hero.

Courtesy of DC Comics

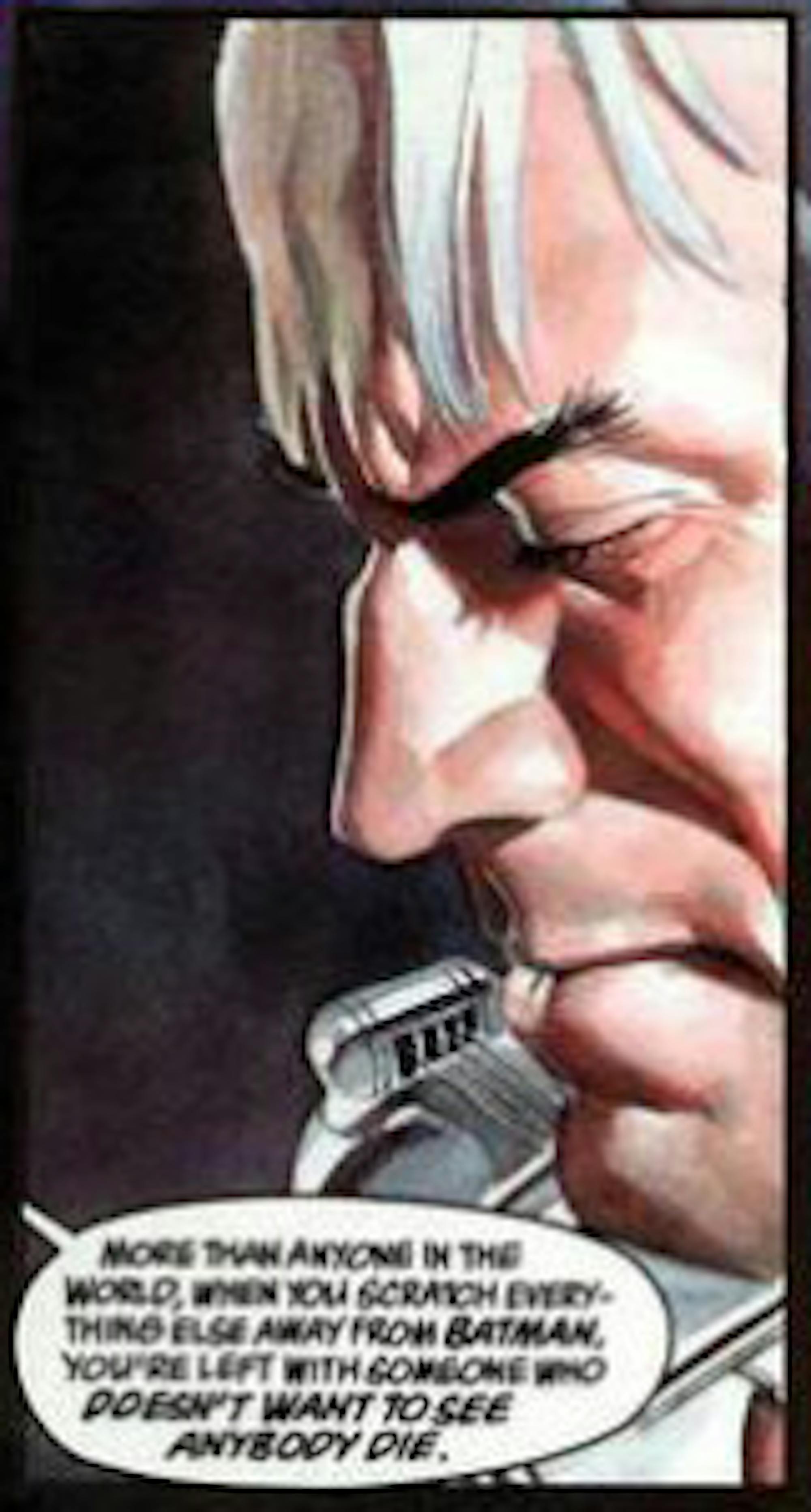

The world needs a Batman, too.

There’s something truly understandable about the Batman fantasy. He’s broken inside, torn apart and reconstituted into a figure of dark power. He is the idea that a man can rise up from among us and do his best to exert his power to save the people around him —that no matter how far you’ve been pushed, it is possible to never break your rules and to never give in. He’s a reminder that being broken does not mean you cannot put the world around you back together again.

Courtesy of DC Comics

The world needs both of them now.

On March 22, the day that I went to see Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, the morning news reported that a terrorist attack in Brussels had claimed 30 lives and injured 200 people. On the heels of attacks in Turkey (two in the most recent memory and the fourth this month), Pakistan, Nigeria and countless others, there’s a need for a large-scale cultural breather.

What seems to be the biggest film of the year stars two characters that stand for so much: for hope, for justice, for the promise that we can make the world better. Batman and Superman are two mythological titans that offer a chance to find some greater meaning victories. At least, that’s what I hoped for when I walked in.

Instead, I was given something horrifying. The film appropriated 9/11 imagery, failing to fully understand its significance. We watched the horrified faces of the citizens of Metropolis as their city crumbled around them, violence, darkness and bloodshed abounded.

Superman was selfish. Rather than being someone greater, he was someone only willing to save those close to him. Lois Lane was threatened, Martha Kent was kidnapped and he put himself in danger. These are what spurred this Superman to action. He’s a man of constant conflict and sorrow, seeking to help himself rather than others. He flew away from an explosion that killed dozens and left the world behind. Sure, the film shows him saving others, but it is lip service paid for visual splendor; it is nothing that carries weight.

Batman was brutal. His darkness overwhelmed him, leading him down a path of violence. He branded criminals, which we’re told is a prison death sentence in Gotham. He slammed his vehicle on top of cars and fires actual guns, like the ones that killed his parents, at people to burn them alive and at cars full of people that can explode. The setting in which we are introduced to him is similar to that of a horror movie villain, a dank basement filled with Asian sex slaves whom he has just rescued from their captor. The police walk in, and he’s hiding in the corner, ready to pounce like some sick monster.

During the week that we needed them most, the two heroes who defined what it meant to be a superhero were overwhelmed by darkness and selfishness. Those we were supposed to aspire to were overwhelmed by cynical understandings of what it meant to be a dark and “mature” film.

Now where did that darkness originate from? Why don’t we take a look at a few statements from director Zack Snyder.

On the use of Jimmy Olsen, Superman’s best pal and the guy who believes the most in Superman’s goodness:

“We just did it as this little aside because we had been tracking where we thought the movies were gonna go, and we don’t have room for Jimmy Olsen in our big pantheon of characters, but we can have fun with him, right?”

Putting a gun to his head and blowing his brains out were the “fun with him.”

In all but a few interpretations, Batman never breaks his rule to never directly take a life.

“So, I tried to do it by proxy. Shoot the car they’re in, the car blows up or the grenade would go off in the guy’s hand, or when he shoots the tank and the guy pretty much lights the tank [himself]. I perceive it as him not killing directly, but if the bad guys are associated with a thing that happens to blow up, he would say, ‘That that’s not really my problem.’”

“A little more like manslaughter than murder, although I would say that in the Frank Miller comic book that I reference, he kills all the time. There’s a scene from the graphic novel where he busts through a wall, takes the guy’s machine gun … I took that little vignette from a scene in The Dark Knight Returns, and at the end of that, he shoots the guy right between the eyes with the machine gun. One shot. Of course, I went to the gas tank, and all of the guys I work with were like, ‘You’ve gotta shoot him in the head’ because they’re all comic book dorks, and I was like, ‘I’m not gonna be the guy that does that!’”

Courtesy of DC Comics

I will inform non-comic readers that the Frank Miller comic that Snyder referenced not only featured a scene in which he eschewed guns, but also was an alternate reality that challenged Batman’s limits and functioned as a deconstruction of the character, rather than a reference point.

That’s an interesting word, deconstruction. Deconstruction refers to an actual movement in comic book, specifically superhero comic book, writing. Deconstruction seeks to understand the implications and ideas that underlie these heroes, break them down and work through them in the stories. This process occurs most famously in Watchmen and also in The Dark Knight Returns.

Funnily enough, these are both books that either have their fingerprints all over Snyder’s work (BvS is loaded with references to The Dark Knight Returns)or were adapted directly, like Watchmen. At some point, Snyder seemed to lose all interest in what these superheroes fundamentally stand for and focused his attention on what he could bring into them and what he could break down out of them.

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice seems to be the product of someone who doesn’t believe in these heroes. I mean, he pays lip service to it, of course. The movie’s climax hinges on the obscure piece of comic book trivia that Batman and Superman’s mothers have the same name. The movie is loaded with references and DC Comics characters that fly over the audience’s head.

But knowledge is not care. I believe that there’s an aesthetic interest. But it’s important for Snyder to also get into the core of the interest; however, there is no desire to go in that direction. Who are these characters? What do they represent?

Certainly they’re no one I recognize, nor do they represent anything they should. And that’s the fundamental problem. It’s a film that seeks to avoid adapting the core conceptions of its two characters.

I’m more than willing to acknowledge that characters change and that there are different conceptions. I hear already the calls that these are “more realistic” and “grounded” conceptions, that there are in-story reasons for why these characters do what they do.

“Batman is so brutal,” they say. “It is clear he has been pushed to the limits by the Joker and the destruction in Metropolis.”

“Superman is still young; he’ll have time to grow. He’s still new to the job.”

By the way, he’s been at it for a year and a half.

Well, besides leveling the charge that those aren’t well-explained or well-conceived, the bigger question I have to ask is why “realism” or “grounding” ever enters the conversation. These are superheroes — people wearing tights with extraordinary powers. They aren’t grounded in reality. They’re modern mythos; they stand for something greater, something more aspirational, something beyond simple “realistic psychology.”

BvS is a film that fails to understand that importance. It’s a film that fails to understand that these two are symbolic figures, not real-world figures.

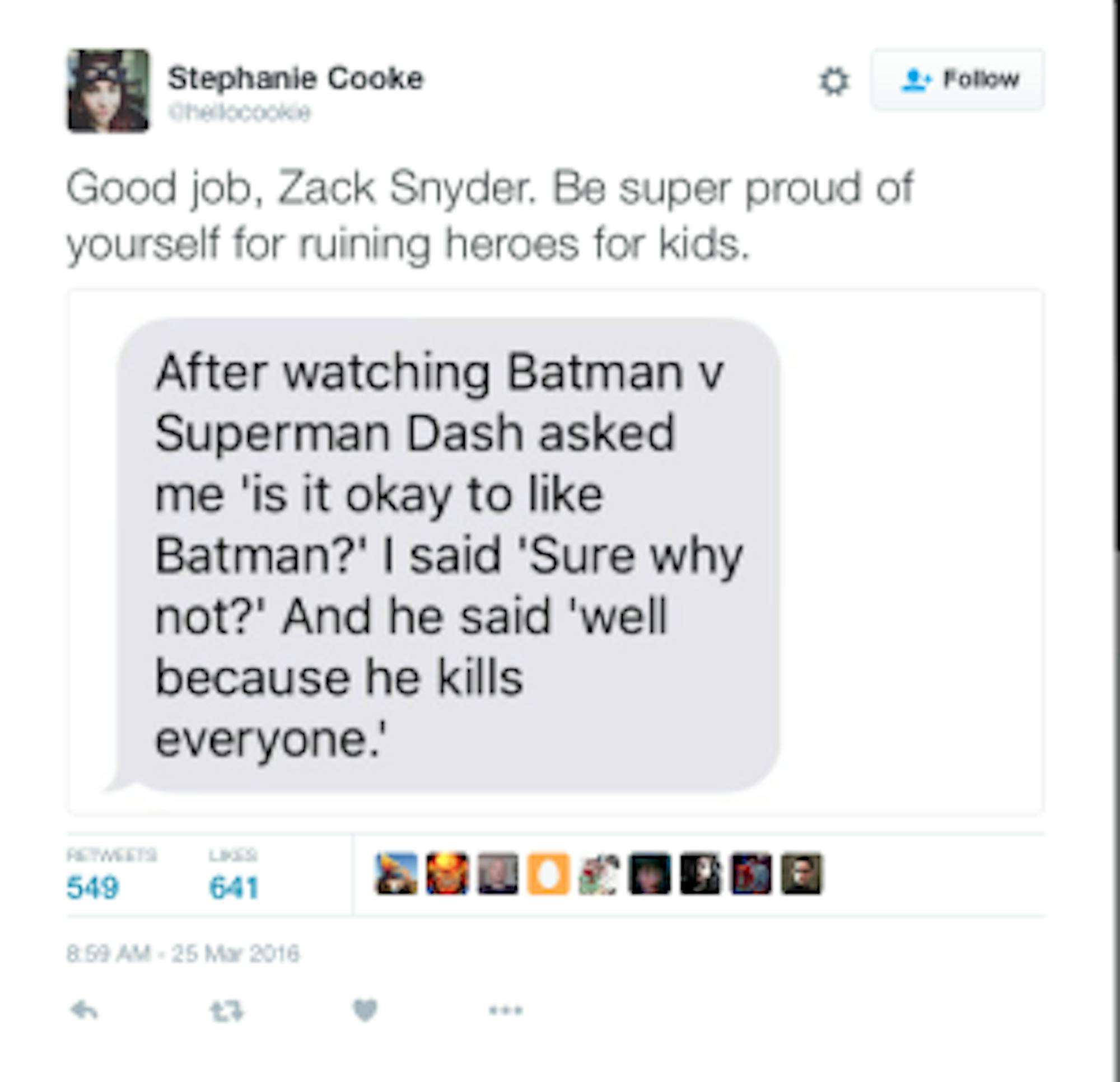

It’s a film about childhood idols that can’t be watched by children.

Courtesy of hellocookie/twitter

It’s a film that takes a symbol of hope and breaks it in half through death. It’s a film that takes the symbol of “an ideal to strive towards” and kills him for a pointless self-sacrifice. All I believe is that Snyder thought that it would be really cool to deal with Superman dying and that he really wanted Batman to put the Justice League together.

It’s a film that could inspire hope. But it doesn’t.