Content Warning: This article contains references to suicide.

The student body at Emory University never ceases to amaze me. As I scroll through my LinkedIn connections, my mouth gapes at what my peers accomplished before college — everything from an internship with the United Nations to the President’s Volunteer Service Award and researching with an esteemed medical school. I cannot comprehend how any student could fit such commitments into their high school schedules. But then I remember that this was me too. Reflecting on the years before I came to Emory, I recall nights when I would not come home until late evening, my day crammed full of extracurriculars.

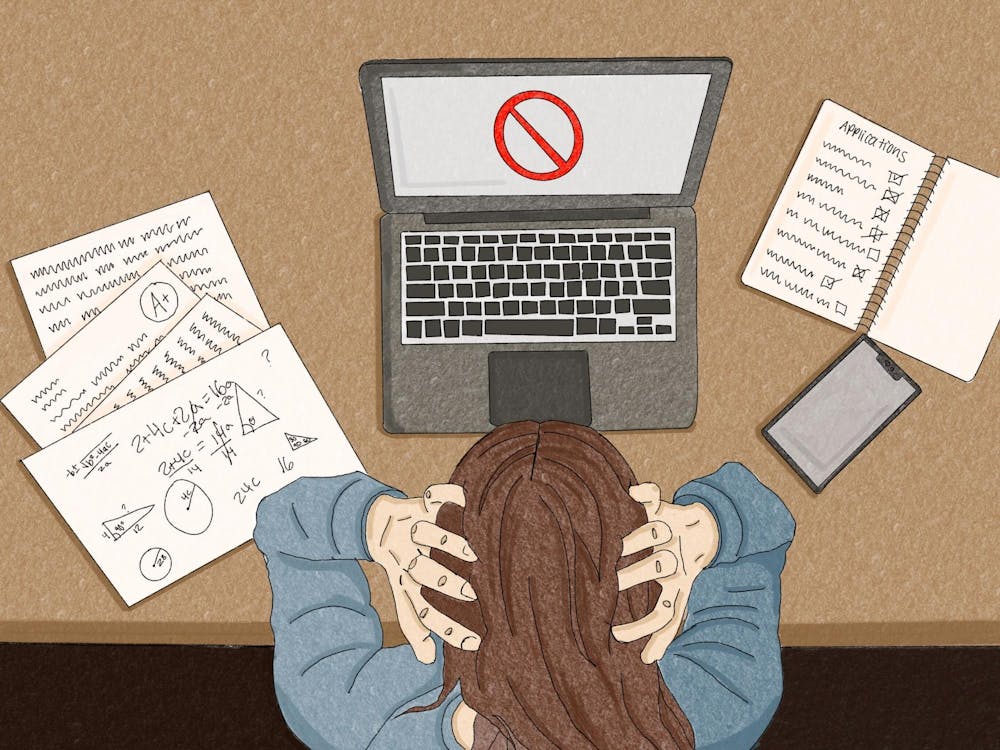

High school students are being depleted of joy from these exhausting schedules, fighting to compete with other students who are equally as tired. College applications often expect students to fill every day with activities, barely allowing any time to rest or make meaningful connections with others. However, we continue to endure the stress because of the increasing pressure to look good on paper. Overachieving students, including myself, aim to use our extracurricular experience to boost the chances of admission to increasingly competitive institutions like Emory.

Originally, I hoped to frame this piece as a call for students to stop viewing extracurricular activities merely as a means to gain acceptance into higher education. Instead, I wanted students to view them as an extension of our service to the community. However, I soon realized that this perspective would only be blaming the victim of this system. The toxic extracurricular culture in higher education admissions is neglecting student well-being. We must demand that colleges change their expectations for students’ extracurricular involvement to promote a shift in how students view and prioritize their well-being.

I did not attend a competitive high school. I busied myself with activities, but my participation in clubs and other activities was not contingent on that of my classmates — it was my choice alone. However, I have heard horror stories of students who drive one another to the brink of insanity, each student piling on more extracurriculars than the next in an attempt to frame themselves as a more competitive applicant. This pressure to be involved leads to stress, tearing down students’ mental health and driving too many to the point of suicidal ideation. I thought this pressure would desist after sending off undergraduate applications, but it didn’t. At Emory, it feels as though this competitive culture persists, with students shifting their eyes to focus on gaining admission to top-ranked graduate schools. Every day, I watch my peers struggle to balance their mass commitments, trying to reap the benefits of the experience they already worked so hard for. With this, we are setting our future doctors, lawyers and entrepreneurs on the wrong path, jeopardizing our society as a whole.

There are a few safeguards during the admissions process, such as a ten activity limit on the Common Application, but institutions have not done enough to halt the destructive spiral students fall into when piling up extracurriculars. It does not matter whether colleges endorse this workload or remain silent: Any action short of denouncing over-involvement speaks that they will reward applicants who will overwork themselves. When looking at profiles of successful applicants to top colleges, I wonder how much they had to sacrifice to boast such packed resumes. The solution to the extracurricular crisis is not to ask applicants to place limits on their involvement. Rather, colleges must lead the fight to pull their applicants out of unhealthy, overloaded schedules by encouraging them to focus on what they’re passionate about. Students only wish to obtain the best future, and it is not their fault for straining themselves to have a higher chance of succeeding.

College applicants are not the only victims of lacking restrictions on extracurriculars — groups benefited by a student’s artificial community outreach have the potential to be harmed, too. Suppose a student dedicates time to tutoring low-income elementary schoolers on the weekends for their college application — without passion or drive outside of admission to college, they potentially lack the motivation to do their job well or consistently. If that student only joins for their appearances on paper and neglects their service due to spreading themselves too thin, then those elementary schoolers will lack the necessary services. Neither party deserves to be in that situation.

Several people I knew from other high schools championed incredible work in the nonprofits they founded. From leading intercultural exchanges to providing translation services, these students were model volunteers — but tossed those goals in the trash when they were accepted to their dream colleges. Communities lean on these services, but to the founders of those nonprofits, they were only an afterthought.

Students need to refocus on the passion that should lie at the center of extracurricular engagement. Rather than stuffing our days full of activities we don’t truly care about, we should be investing time in activities that both feed our souls and the souls of those around us. When I came to Emory, I quit this competition and refused to participate in activities I was not genuinely passionate about, even if they didn’t amount to as much as what others pursued. Yet, I understood that I may be trading my chances at a top graduate school. This is a decision I made personally, knowing that not everyone has this luxury.

To make this change, both in students’ minds and institutionally, we can start by halving the number of activity slots fillable on the Common Application to five and creating a minimum of hours that applicants can list per activity — two changes that would create a much-needed safety net, preventing applicants from extending themselves to a point that they lose their sense of joy just to fill boxes. Colleges have already shown that they are capable of being more in touch with students: The test-optional and test-blind policies enacted by many schools reveal that they are not completely oblivious of the toll of their process. Now, colleges must apply this same thought to the non-academic sphere. In reviewing applications, I urge Emory admissions counselors to not prioritize over-involvement, and instead focus on activities that applicants’ hearts are actually in. We must be able to enjoy activities — as colleges claim they wish for us — but that is only possible when we are not working ourselves to the bone. In an age requiring students to stretch themselves thin to reach our dreams, college admissions systems must be designed to allow us to find passion in extracurriculars, starting with these tangible ways.

I am terrified that a system that should be helping us to craft our futures is only poisoning them. Glorifying overloaded extracurricular schedules prevents us from seeing activities as an opportunity to actually enact change and disallows us from giving help to those who depend on it. I do not want to see another one of my brilliant peers churned through this vicious system that chews up passions and spits them out as chores. We must fix extracurricular culture — our futures depend on it.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of self-harm or suicide, you can call Student Intervention Services at (404) 430-1120 or reach Emory’s Counseling and Psychological Services at (404) 727-7450 or https://counseling.emory.edu/. You can reach the Georgia Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7 at (800) 273-TALK (8255) and the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline 24/7 at 988.

Contact Josselyn St. Clair at jmstcla@emory.edu