A few months ago, a reporter at The Emory Wheel asked one of us in an email about Emory University professors’ views on “the new levels of surveillance on Emory's campus, including the addition of cameras on the quad and changes to the signage policy.” While the article is not yet published, we, four professors across Emory’s schools, wanted to state our views on the additional surveillance in the more sustained form of this op-ed. We hope and expect that more representative bodies will make more formal statements on behalf of larger groups of faculty.

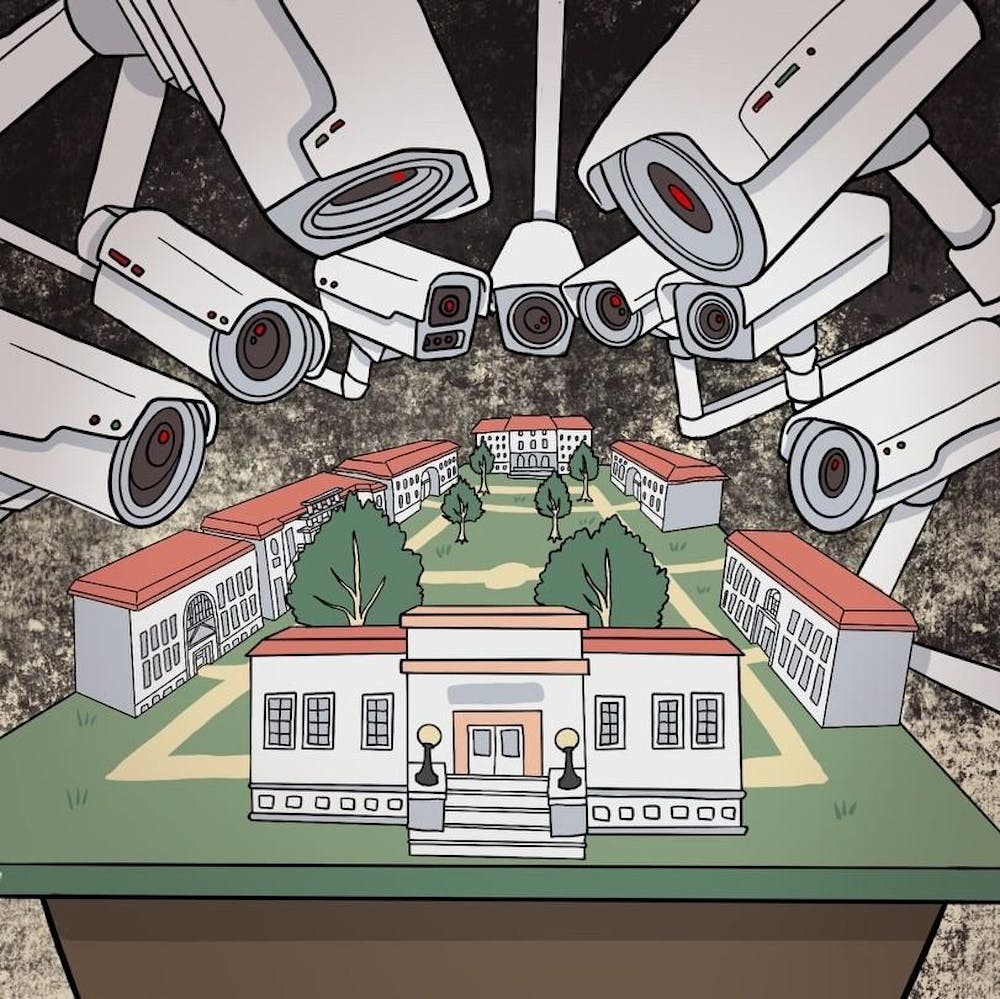

The Emory News Center noted on April 30, with an update on May 3, that the University had “added more lighting and additional cameras covering key campus locations.” It added that “these cameras are monitored 24/7 by the Emory Police Department.” We know of no broad-based deliberative process, like a consultation with the University Senate, that led to this decision to expand surveillance. The only formal justification that we have heard is that surveillance was expanded “to further enhance the safety of our community.”

This rhetoric of safety has flowed through official University announcements in recent months. In the wake of police action against those gathered on the Emory Quadrangle on April 25, Emory President Gregory Fenves stressed his commitment to campus safety in statements on April 28 and 29. Both the Emory News Center’s April 30 update and Fenves’ May 6 letter to the community invoked language of safety in explaining things like increased police presence and expanded surveillance, as well as in explaining why commencement exercises would be held in another county. Months later, he reiterated this concern for safety in a letter on the first day of classes, acknowledging the need to create space “for a respectful and productive exchange of ideas” between people with diverse views. He concluded, “that also means focusing on the safety of everyone who lives, works, and learns at Emory.”

The repeated appeals to “safety” fit with a broader pattern on campuses throughout the United States and in other parts of the world, in which administrations have invoked safety to justify expanding surveillance and taking other actions that can suppress the free intellectual inquiry and debate that are central to the purpose of higher education. In seeking to make the university safe, they threaten its very raison d’etre.

Some level of surveillance for the sake of safety may be necessary in universities — as it sometimes is in government buildings, and other offices, schools and homes. However, prior to any expansion of surveillance, we must ask these questions: What is the nature of the “safety” this surveillance is designed to promote? Whose safety is being protected, and to what end? Who decides how the apparatus and rules for its maintenance are put into place? In what ways is the system of surveillance accountable to the community it claims to protect? Who has access to the data collected, and why? These questions need to be considered in forums that are accessible to the full Emory community.

We are especially concerned that new surveillance measures may protect buildings, lawns and public image while threatening the core character and purpose of the University, for surveillance can exert a chilling effect that impedes upon the free exchange of ideas it is supposed to protect. We are also concerned that expanded surveillance will place already vulnerable members of the Emory community at greater risk rather than serving to protect “everyone who lives, works, and learns at Emory,” as Fenves described.

Any surveillance at Emory should be designed, limited, administered and accountable in ways that promote the kind of safety that is necessary for the life and mission of a research university. Public deliberation around surveillance and other security measures is particularly necessary in the wake of the April 25 police actions that involved excessive force against students and faculty and subsequent criminal charges. These charges are proceeding without objection from the University. In this case, actions undertaken in the name of campus security have contributed to the lack of safety of Emory students and faculty. They have powerfully discouraged exactly the free exchange of ideas they are supposed to protect. They therefore put a significant burden of proof on any expansion of surveillance and other security measures.

The threat of surveillance to the core purposes of the University, including teaching, inquiry and the free contest of ideas, is especially acute when cameras are trained on the Quad and other public gathering spaces. We see no demonstrable need for surveillance on the Quad. The Quad does not have a history as a frequent site of violent crime. Instead, it has served as an important space for teaching, learning and debate. Even if surveillance on the Quad marginally reduces the risk of property damage, it threatens the free inquiry and expression that the property — and the whole University — exists to sustain.

The risk of a chilling effect by surveillance is compounded by the doxxing and other forms of online and in-person harassment that faculty, students and staff have faced. Without proper limits, surveillance can become a resource for those who seek to engage in this kind of harassment — and so further suppress the free exchange of ideas through threats or harm to Emory community members. It can undermine the free exchange of ideas in more subtle ways, too. Surveillance mechanisms allow administrators to observe and direct responses to members of the community without actually engaging them.

With these risks in mind, we call upon Emory’s senior leaders to implement a process for public deliberation about surveillance on campus. Surveillance can only support the free exchange of ideas if it is itself subject to the free exchange of ideas. As a first step toward re-establishing the trust that is necessary for this public deliberation to have legitimacy, we ask for the removal of any surveillance that has been installed to monitor the main quadrangles on the Atlanta and Oxford College campuses. We further ask that any surveillance at Emory be announced in the spaces being surveilled with clear signs — as is standard practice in democracies around the globe.

The legitimacy of this proposed deliberative process would also be strengthened if the University made it clear that any surveillance would be for the sake of supporting the free exchange of ideas among all members of the community. More statements cannot do this work: Only actions can. We therefore ask Fenves to formally announce that the Emory administration requests that all charges against faculty and students related to the events of April 25 be dropped by the Office of the Solicitor for DeKalb County. A statement from the president of the University asking that the charges be dropped would surely influence the deliberations of that office.

Regardless of one’s perspective on those events, whatever infractions of the Respect for Open Expression Policy might have occurred on that date were not sufficient to warrant such aggressive police action, including mass arrests and criminal charges against students and faculty. A formal request that the charges be dropped would make a material difference in the lives and prospects — and safety — of the Emory students and faculty who were arrested. It would help create the conditions in which public deliberations about surveillance could be possible. It would also signal the administration’s commitment to the free flow of ideas, information and worldviews that are the life-force of any great university.

Jericho Brown, Dabney Evans, Gyan Pandey and Ted Smith are professors at Emory University. Contact Brown at jerichobro@emory.edu, Evans at devan01@emory.edu, Pandey at gpande2@emory.edu and Smith at ted.smith@emory.edu

![IMG_0064[31].jpeg](https://snworksceo.imgix.net/whl/bd1509fc-0fff-41c3-8a17-14169776d877.sized-1000x1000.jpg?ar=16%3A9&w=500&dpr=2&fit=crop&crop=faces)