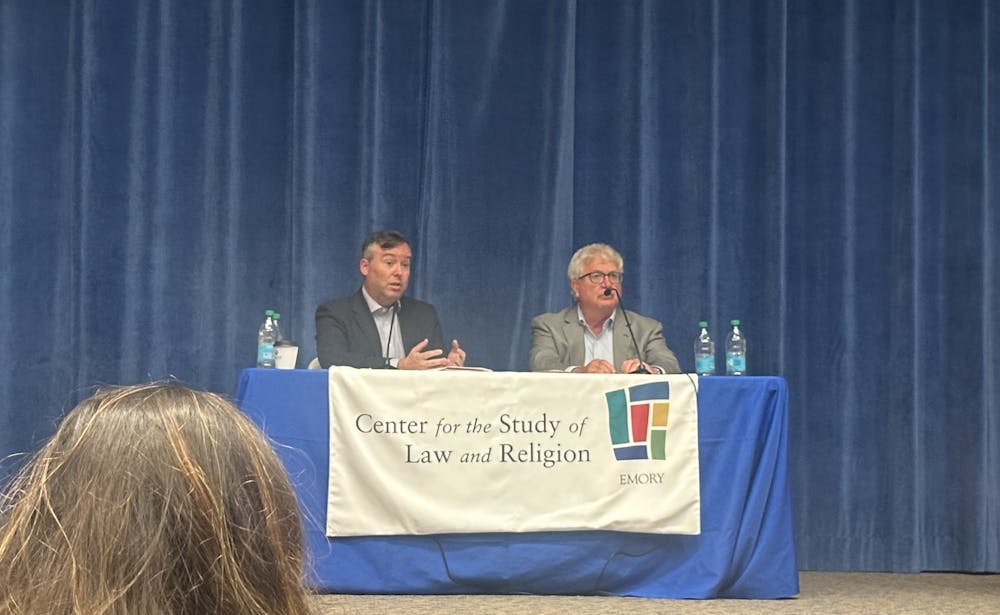

During a talk in Gambrell Hall on Sept. 16, Nathan S. Chapman, A. Gus Cleveland distinguished chair of law at the University of Georgia School of Law, and Michael W. McConnell, Richard and Frances Mallery professor at Stanford Law School (Calif.), discussed their new book “Agreeing to Disagree: How the Establishment Clause Protects Religious Diversity and Freedom of Conscience.” The two legal scholars emphasized the importance of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause in helping Americans find a middle ground.

McConnell, who has argued 16 cases in front of the Supreme Court and today serves as the director of the Stanford Constitutional Law Center, began the conversation by quoting the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

President George W. Bush nominated McConnell to serve as a circuit judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in 2002, but his examination of the Establishment Clause began earlier in his career, when he clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Brennan. Brennan was involved in the landmark 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman case that established the Lemon test, a doctrine with three parts to assess whether the government is violating the Establishment Clause.

McConnell said the pair wrote the book because the Establishment Clause is the most “misunderstood” clause in the U.S. Constitution. According to McConnell, with many advocating a stronger connection between church and state, understanding the history of the clause is crucial. McConnell noted that over the last 20 years, and especially in the last five, religion has been a topic of polarization and disagreement in the United States.

“Our book is an attempt to figure out what establishment means and to argue for why we believe that the Establishment Clause plays an important and continuing role in protecting religious diversity in particular and freedom of conscience in America,” McConnell said.

Chapman and McConnell expressed their disappointment in the Sept. 10 presidential debate because of the candidates’ lack of addressing issues of importance. They emphasized the importance of politicians showing a willingness to recognize and attempt to understand one another’s beliefs and using their platforms to propose solutions to issues. For instance, the authors discussed how underfunded public schools historically fall behind religious schools.

“I wish our candidates for president were talking about how to solve this problem instead of talking about gobbling up cats and dogs,” Chapman said.

Following the talk, Chapman discussed the relation of the book’s title to its content.

“What would it look like to have a society that, rather than fighting tooth and nail against each other on matters where we disagree, if we actually agree to allow one another to live?” Chapman said. “What would it look like to sort of disagree heartily with one another in public and give solid reasons and then allow one another to sort of live their lives within their sub normative communities?”

A Q&A session followed the talk, with many students questioning the nuances surrounding constitutional law and its application.

Alex Chiang (25L) asked about whether the Supreme Court would “incorporate freedom of conscience into the Establishment Clause.”

Chiang said he was inspired to ask about freedom of conscience after taking Witte’s course ES 684 “First Amendment: Religious Liberty.”

“That was one of the questions I had coming out of that course,” Chiang said. “Especially given that a lot of the source material and a lot of this discussion was based on the Establishment Clause and how the Establishment Clause is going to be going forward, I thought … the Supreme Court could incorporate freedom of conscience into the Establishment Clause.”

Witte noted that the CSLR welcomes all viewpoints and engages with opinions from students and faculty.

“It’s important that while this is a Methodist-founded university, this is a university that welcomes any and all perspectives — religious and non-religious and anti-religious viewpoints are all represented on the campus,” Witte said. “Our Center for the Study of Law and Religion is premised on that latter understanding, that religion is an important dimension of human life and human society.”

CSLR Executive Director Whittney Barth emphasized the importance of disagreement and urged people to be engaged and informed in conversations surrounding religion.

“We encourage disagreement, and I will say, we have disagreement even within our center,” Barth said. “We are a nonpartisan center, and we do not have to have a particular view on law and religion in order to be part of the center.”

Students are evidently engaged and interested in utilizing Emory University’s emphasis on free speech to maximize their understanding and their own voice. Natalie Garcia-Ramos (27C), who described herself as an aspiring lawyer, related the scholars’ discussion to her own experience as a college student.

“It’s really important to understand the role that the Establishment Clause has in formal laws in order to actually understand what politicians are saying and what they’re proposing, and we can know what to vote for and what we believe,” Garcia-Ramos said.

Chapman and McConnell’s discourse demonstrated that policies as historic as the Establishment Clause still contain room for change.

“It’s not really ‘should there be any relationship between [church and state]’ but what should that relationship be,” Chapman said.

Jacob Muscolino (he/him) (28C) is a News Editor at The Emory Wheel. He is from Long Island and plans to major in History and Psychology. Outside of the Wheel, he is involved in Emory Reads and Emory Economics Review. You can often find Jacob watching the newest blockbuster for his Letterboxd, dissecting The New York Times and traveling to the next destination on his bucket list.