Boycott culture is the unfortunate love child of cancel culture. While cancel culture focuses on calling out — and publicly shaming — individuals and companies online, boycott culture has evolved into a powerful tool for organized consumer action against businesses. As these two complementary phenomena merge and expand into wider social and economic forces, one thing is clear: It's time for a complete overhaul.

Boycott culture manifests as collective divestment from corporations that either support or are complacent political, social and cultural injustices. These online offensives gain traction like tabloid stories, featuring shocking new pieces of media about a businesses’ affiliations and work ethics, and then die down quickly as the world forgets and moves to the next cause. Boycotts’ frequent lack of fact-based social media outreach often demerit valid stances and undermine the importance of action. For example, the entire McDonald's boycott in the Middle East was sparked by one independent franchise operator’s actions in support of Israel which were subsequently denied by the corporation. We need to focus on grassroots community mobilization instead of performative online outrage.

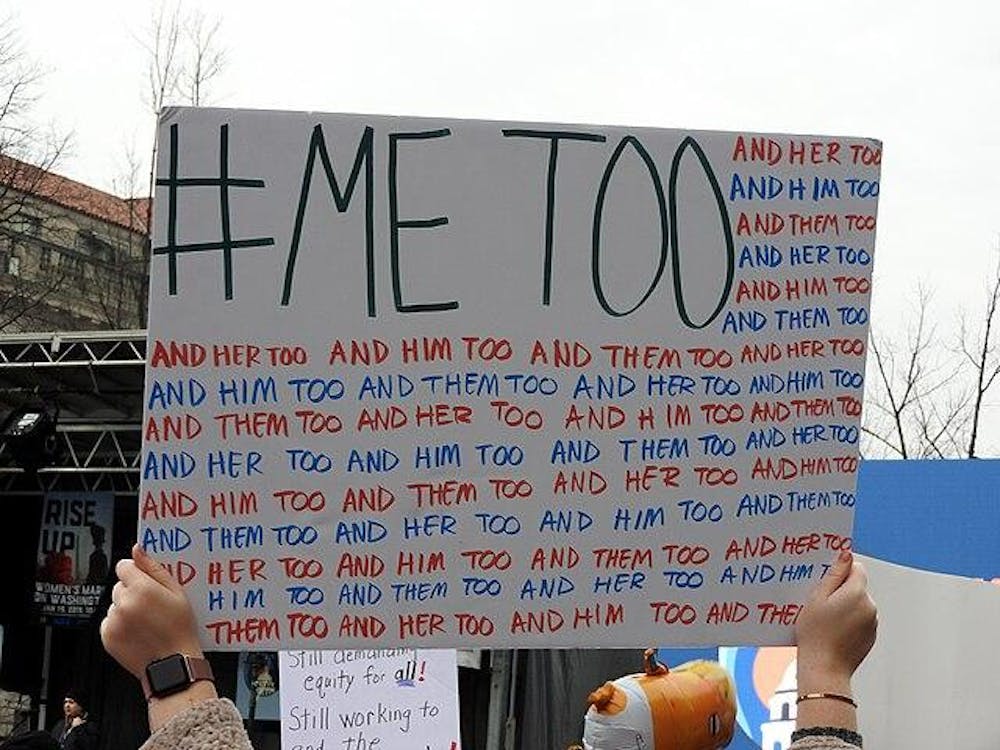

The foundations of today’s boycott culture were laid by popular internet movements like the #MeToo movement and climate activist Greta Thunberg’s Fridays for Future. Both of these movements were driven by internet-facilitated cultural globalization and focused on fundamental human rights. Activists called out various stakeholders, from sexual perpetrators to corrupt governments, challenging both individuals and institutions to re-evaluate current policies and practices.

These movements were like mass boycotts, in that frustration with a particular cause led to socially charged acts of resistance, accompanied by demands for change. This makes it clear that movements can become boycotts, but internet-driven boycotts are futile because they rarely become movements. For example, Fridays for Future, a movement initiated to increase political action on climate change, led to students boycotting schools in protest. However, pro-Palestine activists’ recent Starbucks and McDonalds boycott was framed as a movement to boycott Starbucks due to their alleged support of the Israeli state, therefore shifting the frame of focus from collective social action to symbolic consumer gestures with limited long-term impact.

Interested in the goals behind these boycotts, I asked a friend of mine why students are boycotting Starbucks. My friend, who had reposted “brands to boycott” Instagram stories, had no idea why the movement had started. Further, the anti-corporation fervor never made its way to my family in India, where the average population was blissfully unaware due to a lack of media coverage, sipping their Starbucks chai tea lattes — beverages from an organization that criticized its worker union’s solidarity with Palestine.

However, this is not to say that corporate boycott culture does not work. Boycotting Starbucks decreased the company’s revenue in the Middle East, even pushing their stores to release their ever-popular fall products early to regain consumer traction in the United States.

In the long term, these uprisings also changed American corporations’ thought processes around public protest. Corporations became much more fearful of how these movements would impact their brand image, and thus their bottom-line profits. On the people-facing front, boycotts facilitated a strong wave of positive community-building on Instagram, Twitter and other online forums. Social media users, primarily Gen-Z, learned of global situations, facilitating discussion amongst friend circles and engaging communities online with conversations calling for change. This collective constructive approach was a monumental departure from the black hole of cancel culture.

Today, cancel culture is a normal phenomenon on the internet. Cancellations are an everyday — even every second — practice on Instagram and TikTok. Cancel culture has become synonymous with calling individuals out on their actions by constantly scrutinizing the smallest flaws in an individual’s actions. By enabling users to cancel a company or a person, the internet has become a tool to spread hate. All it takes is one press of a button.

This immediate nature of cancel culture leads to quick responses, but wielding the benefits of an effective boycott requires a different approach — one that emphasizes playing the long game. By systematically dismantling a company’s stronghold at a grassroots level, boycotts could facilitate long-term change, but only if we start critically analyzing and questioning policies without making an immediate call to boycott a company. Our efforts should prioritize grassroots mobilization and community education, ensuring that actions are informed and sustainable rather than performative. Additionally, we need to foster nuanced conversations that critically evaluate company policies. This can help create a more thoughtful approach, avoiding the simplistic, all-or-nothing mindset that often accompanies boycotts otherwise.

Given its complex nature, it’s unreasonable to expect immediate change with these boycotts. Being a student at a college like Emory, where so many diverse opinions exist in tandem, the black-and-white nature of boycott culture is more evident than ever — it permanently brands something as all good or all bad. Our debates and discussions range on a spectrum, and that’s part of the beautiful complexity of human nature. The expectation that a boycott may start a fire from that spark of change is far-fetched. Instead, we must use media outrage to fuel a flame that burns stronger than the latest, and soon-to-be short-lived, Instagram trend. Rebranding boycott culture will be a slow process but one that can ultimately bring us more impactful action.

Inesha Gupta (she/her) (27C) is double majoring in Environmental Science and Business. She is from New Delhi, India, and considers herself a local food expert. She likes to hike, run, read and watch TV shows on 2x in her free time.