Hayley Powers/Visual Editor

Hayley Powers/Visual Editor

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide.

Katie Meyer was a force to be reckoned with. An honor roll student at Stanford University (Calif.), Meyer planned to earn an undergraduate degree in international relations and history and dreamed of attending Stanford Law School. Young girls looked up to her and her classmates turned to her when they needed a laugh, certain they would find solace in her “radiant” and “brilliant” personality. She was the daughter of proud parents, a beloved sister and a fiercely loyal friend. By all accounts, she was a promising young woman capable of achieving anything.

Meyer had high standards for herself in all areas of life and her soccer career was no exception. A standout goalkeeper for Stanford’s women’s soccer team, Meyer started in all but one of the 50 matches she played in during her three years between the posts. She led the team to a national championship as a sophomore in 2019, captured two Pac-12 Championship titles and served as a captain her junior and senior seasons.

Like most student-athletes, Meyer cherished her teammates and was committed to standing by their side. She was so committed, in fact, that she became embroiled in a six-month disciplinary investigation for defending a teammate who was involved in an unspecified “incident.” When Stanford sent her a lengthy email on the night of Feb. 28, 2022 informing her of an impending disciplinary hearing, Meyer – a high-achiever familiar with the pressures of effortless perfection – must have felt as if the walls were closing in.

In the early hours of March 1, Meyer committed suicide in her dorm room. She was 22 years old and less than three months away from graduating.

Meyer’s death left her family reeling and shocked the Stanford community. Stanford alumni publicly scorned their alma mater’s callous, careless handling of the investigation, while the administration hastened to cover their tracks and keep the details under wraps. In the days following Meyer’s death, Stanford announced it would redouble its efforts to promote campus mental health services by hiring more mental health professionals and consulting with psychiatric experts to discuss additional future improvements. It was a belated public relations ploy better suited for saving face than saving lives.

While Meyer’s death was one of the most widely covered student-athlete suicides in recent years, it was by no means an isolated incident. A string of deaths within a few months, including those of 20-year-old James Madison University (Va.) catcher Lauren Bernett, 19-year-old Southern University and A&M College (La.) cheerleader Arlana Miller and 21-year-old University of Wisconsin cross-country and track and field runner Sarah Shulze, exposed the treacherous state of mental health in college athletics.

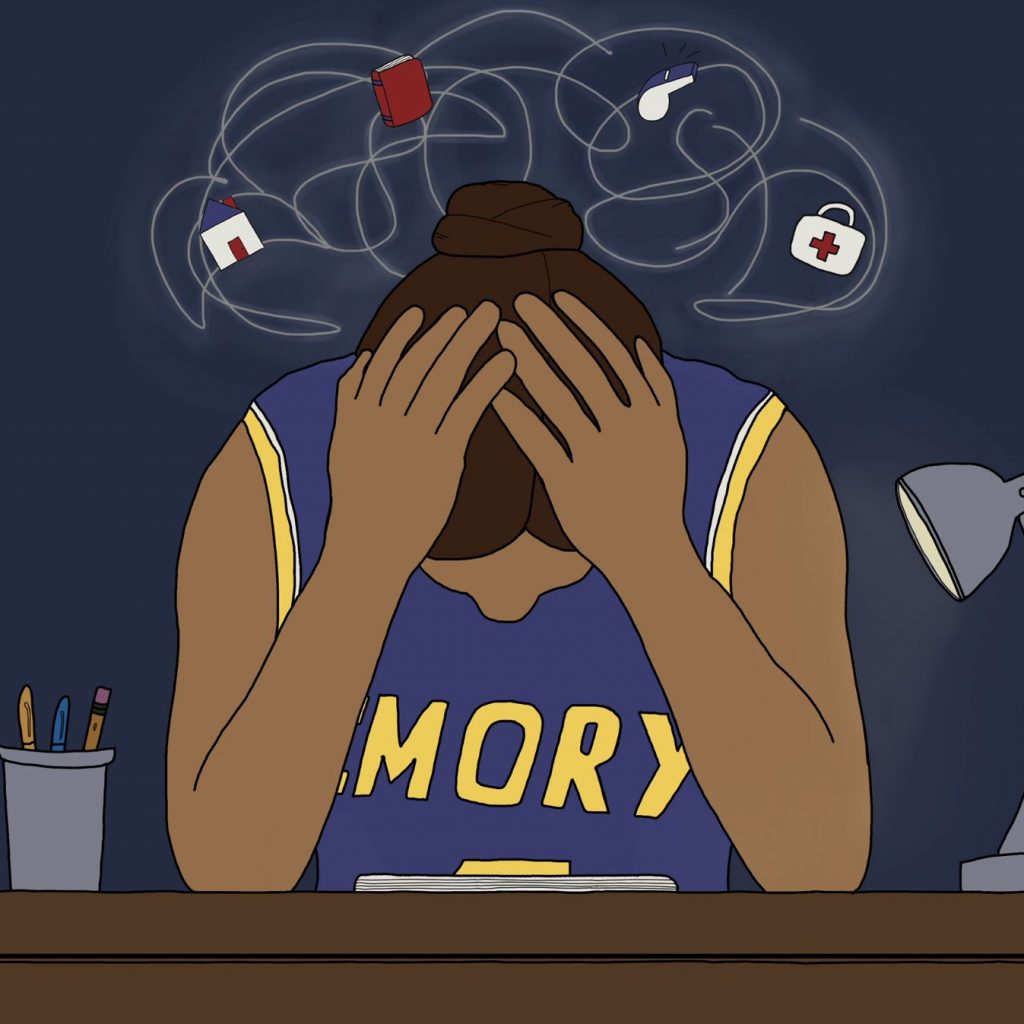

It is no secret that student-athletes are tasked with mediating a multitude of stressors as they adjust to living away from home, performing at a highly competitive athletic level and keeping up with demanding schoolwork. They should not be expected to know instinctively how to manage it all or to weather their darkest storms in isolation. Institutions are supposed to safeguard their athletes’ mental health and enable them to thrive; however, the deaths of Meyer and her peers have made it glaringly obvious that college sports administrators are failing in that responsibility.

A suicide is never anyone’s fault. Even so, the premature deaths of so many strong, intelligent and charismatic young athletes belie the faults in the foundation of college athletics. Student-athletes have a curated team of athletic trainers, coaches and teammates at their disposal, yet they routinely feel as if they have no one to turn to in times of desperation. Pointing fingers and shifting blame when tragedies occur only prolongs survivors’ suffering, but owning accountability can spark much-needed reform. Protecting student-athletes’ mental health is assuredly a daunting task, but nothing will change if everyone stands collectively on the sidelines.

So, in the midst of the current mental health crisis in college athletics, who must be held accountable?

Keeping tabs on over 460,000 student-athletes is a large undertaking, but the NCAA must regularly do so if it is to remedy its mental health culture. The Fall 2021 NCAA Student-Athlete Well-Being Study highlighted multiple weaknesses with the NCAA’s attitudes, health services and support systems concerning mental health. The survey results make it abundantly clear that athletes of all demographics experience mental health issues, but women, people of color and LGBTQ individuals suffer the most.

Even though only 56% of male athletes said that they feel positive or very positive about finding a balance between their academics and athletics, that percentage dipped to 47% for females. Nearly half of all female athletes are in constant emotional turmoil, as 47% of them said they feel overwhelmed constantly or almost every day. Out of the athletes who indicated they had considered transferring, 40% of male athletes and 61% of female athletes cited their mental health as one of the primary factors.

Unsurprisingly, LGBTQ individuals and people of color experienced stress and anxiety at consistently higher rates than their white cissgender straight peers in nearly every category. LGBTQ individuals almost unanimously agreed that they feel overwhelmed daily, with 91% of males and 95% of females answering in the affirmative. Over 70% reported frequent mental exhaustion, sadness and loneliness.

Financially insecure student-athletes face a multitude of economic stressors that only compound their college struggles, and people of color are especially vulnerable. When Bryce Gowdy, a Georgia Institute of Technology football recruit, was a teenager, he became the head of his household after his mother escaped her racially discriminatory job and his family was left homeless. Gowdy’s football scholarship and its financial prospects were the lifeline his family desperately needed. However, Gowdy couldn’t reconcile with the guilt of basking in the luxuries of Division I football while his loved ones slept in their car.

On the night of Dec. 30, 2019, 17-year-old Gowdy, feeling “stuck” and facing an impossible dilemma, stepped in front of a train and ended his own life.

Even if Georgia Tech had been aware of the extent of Gowdy’s domestic and emotional troubles, there is little the school could have done to mitigate them. The NCAA has a fraught history of severely restricting the types of financial assistance colleges can provide their players: only Division I athletes can receive full athletic scholarships, and before June 2021, any additional compensation was strictly prohibited. Scholarships and financial aid certainly lessen an athlete’s burden but, as Gowdy’s death emphasizes, they do not eliminate it. The NCAA’s hands-off approach toward improving athletes’ lives off-campus is likely one of the main reasons why only 55% of male athletes and 47% of female athletes believe their school’s athletic department prioritizes mental health.

The culture of neglect even infiltrates student-athletes’ inner circles, as the survey results showed that athletes are often hesitant to speak openly about their struggles with coaches and teammates. Just over half of respondents agree that they would know how to help a teammate who was experiencing mental health issues, and only 59% of males and 50% of females feel that their coaches take mental health concerns seriously. Even more concerning is the apparent proclivity of contentious intra-team relationships, as 56% of females and 34% of males who considered transferring cited a conflict with a coach or teammate as a motivating factor.

If student-athletes can’t create a safe space to discuss mental health with their closest peers and mentors, the likelihood of them gathering the courage to open up to a mental health professional is next to none. Given that the NCAA has taken no initiative toward mandating guaranteed mental health resources – for which only the Division I Power Five conferences have successfully lobbied – the onus is on individual colleges to build an effective, accessible psychiatric infrastructure tailored to their student-athletes’ needs.

The restructuring process for Emory University began around six years ago, when the NCAA identified refining its mental health policies as a “strategic priority,” according to head athletics trainer John Dunham. The athletics department developed a student-athlete mental health questionnaire, increased collaboration with Emory’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) and formed an athletics care team, of which Dunham is a member. Even with all the progress they have made, Dunham said he and his colleagues recognized that they lacked the expertise of a mental health professional, without whom they could not fully care for Emory student-athletes.

“We just saw the need [for a mental health professional],” Dunham said. “We spend so much time with the students . . . and we saw some of the struggles they were having. From a strategic standpoint, having somebody embedded in athletics that can help day-to-day gives a professional [level of care.]”

Filling that gap involved hiring Kalyn Wilson. Wilson is a licensed social worker and former CAPS clinician who was hired as the coordinator of mental health services in athletics and recreation. She works exclusively with student-athletes and oversees all the mental health services, programming and consultation within the athletic department. A self-proclaimed “holistic provider,” Wilson has mainly focused on fostering personal connections with athletes and proactively checking in with them to prevent major setbacks down the road.

“Asking is the power,” Wilson said. “Asking and creating the space to say, ‘You can let me know what you need.’ From the top, we get to create very, very integrated plans to support the student preemptively in the semester.”

Coming forward with their struggles can be counterintuitive for student-athletes, for whom the refrain “no pain, no gain” has become the standard during intense workouts. Athletes are constantly nursing injuries and pushing their bodies to their limits. They are master compartmentalizers, a skill set that Dunham said does not serve them well when it comes to evaluating their own mental health.

“Pain is part of what they do,” Dunham said. “[They are] playing through pain in a national championship game, and they block that out. Athletes have a great way of segmenting problems . . . It’s really hard for anyone, not just student-athletes, to say, “I feel sad. I don’t feel well.’”

Wilson said that, given all that student-athletes have to juggle, they sometimes feel as though they can’t afford to make room in their schedules for any other commitments. Coordinating built-in mental health activities and encouraging coaches to be vocal about the importance of self-care is one of Wilson’s major focuses. She meets with athletes both individually and in group settings, the latter of which has been especially effective and popular with the athletes.

“[Team-based interventions] are probably the most effective ones because we get to meet them at practice,” Wilson said. “There’s no extra time in the day that we have to carve out, which really speaks to the commitment of the coaching staff, to make sure that they get that help.”

Dunham said student-athletes often struggle to grasp the reality that physical injuries and mental challenges can be equally devastating, a disconnect which reflects the attitude of society. Emory has committed itself to creating a sports culture in which student-athletes know addressing mental health concerns is not a sign of weakness; rather, it is a necessary step toward maximizing their athletic potential.

“Ultimately, shifting the conversation around vulnerability through strength is so key to breaking stigma,” Wilson said. “Visibility breaks stigma. Vulnerability breaks stigma . . . It’s okay not to be okay. That is the point where we’re really making the shift.”

Graduate student midfielder Mara Rodriguez appreciates Wilson’s efforts to meet with them within scheduled practice and while she has never visited Wilson individually, she “knows that she’s always there when [she’s] going through something.” Rodriguez previously played soccer at West Virginia University and Providence College (R.I.), both competitive NCAA Division I programs. She is also a member of the El Salvador women’s national team, so she is no stranger to the pressures of performing well. Rodriguez is very open about the feeling of doubt being ever-present in the beginning of her collegiate career, yet she has remained positive about her experiences.

“I personally found myself in the beginning, stressing over every little pass that I made, or every little touch that I had on the ball or every time I lost the ball,” Rodriguez said. “And I would find myself replaying those moments in my head throughout the game or a day after the game… it took me some time to really realize that that is not beneficial at all.”

Rodriguez experienced her share of setbacks after tearing her ACL in her junior year at Providence. The injury and its long recovery time coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, making it more difficult as daily life was also disrupted. Rodriguez said this was her first real injury and was “without a doubt the hardest time that [she’d] ever been through.” After dedicating so much time and effort to her sport, a cold break from soccer threw her off kilter.

“Having to deal with being on the sidelines for nine plus months, just not being able to walk for two months, being on crutches, which are very challenging, not being able to work out,” Rodriguez said. “Something that I love to do is just workout even if it’s not soccer related, that’s my stress reliever, my time away from school. If I’m going through something outside of school, working out is my outlet, what I find joy in, so not having that for that many months was very hard for me.”

Rodriguez found it beneficial to focus on minor victories when her injury felt overbearing. She met with a sports psychologist during her recovery who provided her advice and assurance. Providence women’s soccer had its own sports psychologist that they could meet with any point. Rodriguez has been privy to caring athletic departments, but some athletes are not as fortunate.

Athletic departments, particularly at Division I schools, have repeatedly failed to properly support their student-athletes. Many athletes suffer with mental health issues, yet they do not seek help because they don’t feel they have an effective support system at their university. Instead, many families and close friends of athletes who have taken their lives after struggling have acted. They have decided that enough is enough and if the institutions are not protecting athletes, then they must take matters in their own hands.

In May 2022, Meyer’s family created Katie’s Save, an organization calling for a widespread policy that they believe could save student lives. The organization strives to institute a policy that “enables and requires the university/school to send a notification to a Designated Advocate regarding instances” where the student may need additional support. Rather than students dealing with issues alone, they choose someone they trust at the beginning of the year who can provide support and comfort if a student requires it. Their mission goes beyond just helping athletes. The Meyer family believes they can help all college students with the implementation of their policy. The Meyer family is frustrated by the unanswered questions they have about Meyer’s situation before her death, and they want to eliminate that for other families.

Morgan Rodgers was a lacrosse player at Duke University (N.C.). During high school, Rodgers suffered from anxiety, but rebounded before heading to Duke. There, she suffered a serious knee injury that left her unable to play for a full year, resulting in a rapid decline in her mental health. This mental transition was hidden to the rest of the world until she died by suicide in July 2019. She was only 22 years old.

Like the Meyer family, Rodgers’ close friends and family took action to prevent other student athletes from suffering alone. They founded Morgan’s Message, an organization aiming “to eliminate the stigma surrounding mental health within the student-athlete community and equalize the treatment of physical and mental health in athletics.” Across the U.S., there are over 1,635 ambassadors of the Morgan’s Message Education Program (MEEP) on 720 campuses. These ambassadors help bridge the gap between athletes and the organization’s resources. Morgan’s Message opens up the conversation on mental health and encourages athletes to speak up about their health.

Organizations like Katie’s Save and Morgan’s Message are valuable resources and outlets for student athletes to discuss their mental health or seek help, but they also prove just how badly school administrations are failing their athletes. The support that these organizations offer should already be in place. Universities should provide avenues of support before the situation escalates, not offering apologies and reevaluations after it has already occurred.

The NCAA needs to take more steps to do two things: redefine sports culture and its “suck-it-up” mentality, and provide additional support to those who need it. For Division I and Division II athletes, athletic scholarships can become a burden. They feel as if they owe the school their hardwork and dedication to the sport because they are receiving benefits to play for the school. What this ignores, however, is how much the school is profiting off their athletic contributions. There is a boundary to how much a student should offer after receiving this scholarship, and their life is far beyond it.

For Division III athletes, joining a team is the labor of love and often requires athletes to balance their sports with all other forms of daily life. While DI and DII athletes may get academic support, DIII athletes are left on their own to make up classes or work, adding an alternative layer of stress to their collegiate careers.

The NCAA should require schools in all divisions to provide proper mental health resources and make them readily available. The NCAA should create a committee that oversees universities’ mental health resources and their compliance to this requirement. The NCAA currently has a task force that recommends the best practices and education to prioritize mental health, but this is not a direct approach to combating the mental health crisis in college athletics. There needs to be a more hands-on approach, including sports psychologists on campuses, therapists specifically for athletics and other professionals on hand to make it simple for athletes to get the help they need.

Aside from the distribution of new resources, the NCAA must also focus on destigmatizing discussions about mental health. Athletes need to feel reassured that taking a break is beneficial to their training. It is easy for student-athletes to get wrapped up in their responsibilities without taking the proper time away from them. It is up to the NCAA to push recovery as a normal part of training.

Their mandatory rule of one day off of practice per week is not enough. The NCAA also needs to encourage athletes to stop compartmentalizing their emotions outside of their sports. Athletes thrive during a competition by separating pain and fear, but this inhibits their ability to work through negative emotions outside sports. As a guiding organization, the NCAA can change the narrative surrounding mental health.

Emory athletics has already made substantial progress in its offerings to athletes, but there is still room for improvement. Emory is already an academically rigorous school, so student-athletes operate in a tense environment. They are expected to make up for their missed class and work without additional help from the athletic department, which leads to a disadvantage for athletes. The Emory athletic department should work closely with student-athletes to ensure they are getting the academic resources they need. By doing so, student-athletes would be able to better handle stress that comes with balancing work and athletics.

Concurrently, the athletic department can focus on bringing mental health resources to athletes during their scheduled practices. Athletes often feel too busy to relieve stress, so their mental health issues can require more help than they initially required. The women’s soccer meetings with Kalyn are a great example of a team prioritizing their mental health. All Emory teams should have a similar meeting or activity during a sanctioned practice time to routinely have mental health check-ins.

Structural change cannot happen overnight, but mental health acknowledgement and progress benefits student athletes all over the nation. The Meyer family, the Rodgers family, Wilson and Dunham illustrate that there have been steps toward positive change.

Now, it is time for the rest of the country to follow in their footsteps. It is up to athletes to prioritize their mental health and accept that not feeling okay is okay. It is also the responsibility of administration and larger athletic organizations to institute resources and programs that assist athletes in their search for help. Tackling the mental health crisis is daunting, but it can, and needs to, be done.

In Sarah Shulze’s obituary, Shulze’s family writes that “balancing athletics, academics and the demands of every day life overwhelmed her in a single, desperate moment.” Current and future student-athletes must understand that if those moments come to them – and it’s okay if they do – they are brave enough, supported enough and loved more than enough to emerge from them stronger and healthier than before.