Amid the pandemic, my dad traveled halfway across the world with a suitcase filled with Chinese snacks just for me. When school first started, my parents stuffed a box full of food they thought I might enjoy and share with my friends. The box flew from Guangdong to Hong Kong, back to both cities again before arriving in New York and finally Atlanta. I didn’t receive this package until three months later, the day before I was supposed to fly home for winter break.

At home, my dad cooks for me every night. I see him rummaging through the fridge, muttering about what to make me next. He asks me questions at least five times a day wanting to know if I’ve figured out what I need to bring back to college. “I just got home,” I’ll tell him. “We have time.” But he’ll still worry, so he places all my food and belongings neatly in a pile next to my suitcase in case I forget.

To be frank, I had a hard time figuring out where this piece should go. Eventually, I realized that food is more than just a vehicle for cultural, social and political change: it’s a language. It’s one of love, tenderness and inexplicable emotions; but they only exist in the material world to be acted upon, not written down into words.

For Asian parents, cutting fruit is the universal love language. It supersedes any sort of verbal expressions of affection and words of encouragement. Most children from Asian households understand the most basic expectation: get good grades. In my family, it was expected that I prioritize academics and academic-centric extracurriculars over sports and other non-academic clubs like calligraphy. All in all, everything was second to the “A” inked on my transcript.

As cold and fanatical as it might sound, I still know that a bowl of apple and pear slices or washed grapes and blueberries are a symbol of home and my mom and grandma’s unspoken expression of love.

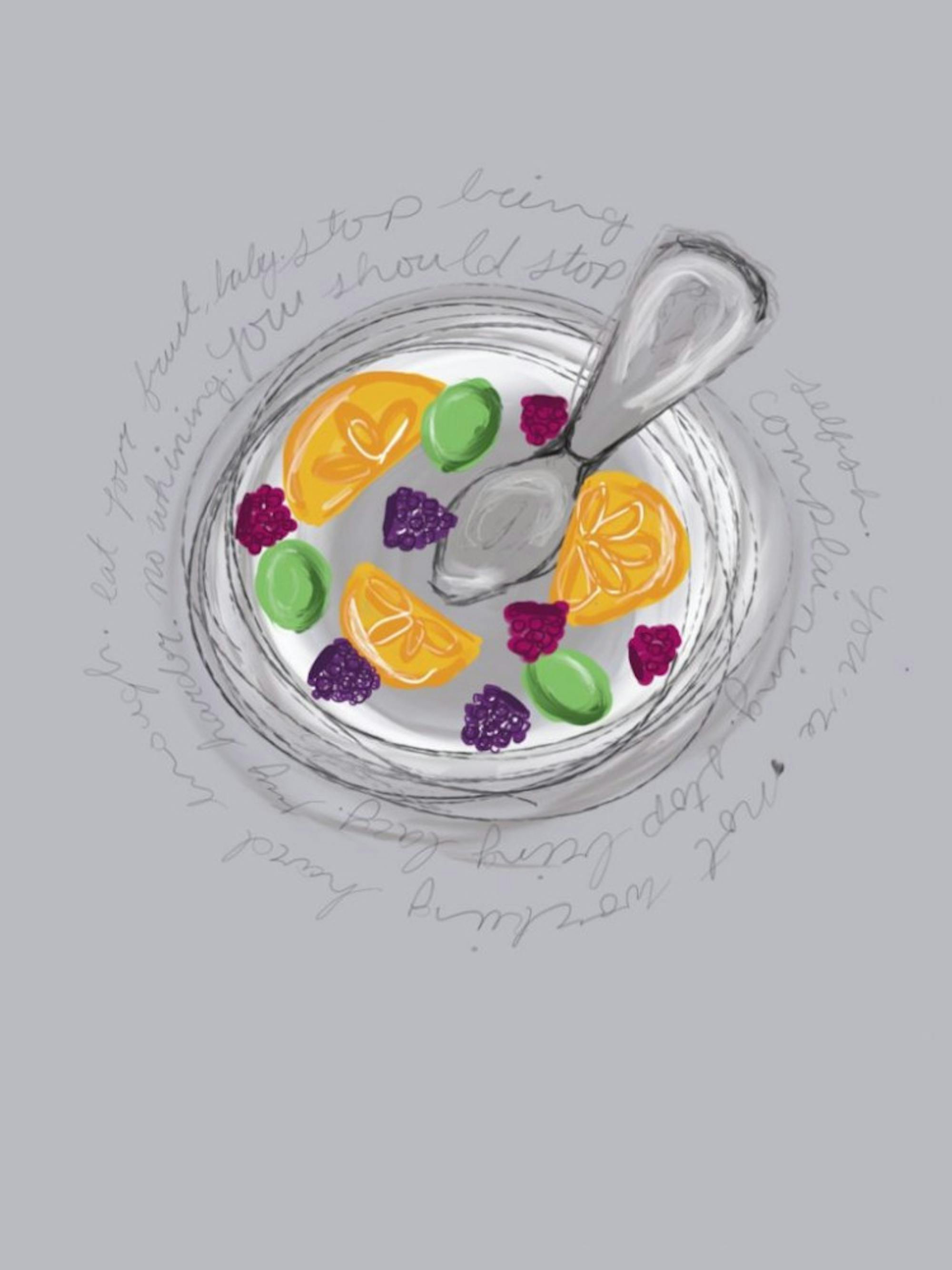

In China, my grandma frequently stayed with me when my parents were out of town. When I came home after school, she would leap off the couch, grab a handful of fruit and ask me if I wanted any to eat. Though I would often decline her requests, more focused on finishing my homework than eating, I would always hear a soft knock on my door less than 10 minutes later. My grandma would walk in with a large array of sliced apples and pears, topped with strawberries (with no stem, of course), blueberries and orange wedges. Once she handed the plate to me, she would close the door and leave. The nice gesture makes the array of fruits sweeter than usual. It’s a reminder to me that though I felt my grandma criticized me for inane things, like looking both ways when I crossed the road, she loved me. And of course, never wanted me to do my homework on an empty stomach.

During high school, I frequently stayed up long past midnight finishing my Calculus WebAssign, writing hail mary essays for English and rehearsing my independent study presentation. Like clockwork, I would hear my mom’s footsteps coming up the stairs every night around 9 p.m., the occasional reprimand of my cat if he tried to get in her way and the door squeaking open as she walked into my room. She would set a plate of cut fruit next to me, briefly rest her hand on my shoulder and leave.

Though my mom stopped cutting fruit for me (for which I fully blame my dentist), it’s a post-meal tradition not to eat dessert, but to share fruit and continue our dinner conversations. So, for 20 minutes of the day, my mom and I cede our time to each other. We engage in productive small talk, an oxymoron in it of itself, but it’s everything unspoken that counts. It’s about my mom grabbing two tangerines and always giving the first one to me; my mom eating the watermelon cubes closer to the rind and leaving me the middle; her fork pushing the sweeter pear slices toward me, and exchanging plums when she sees my face tense up from the sourness.

Now, when I see the metal bowls of uncut fruit in the dining hall at Emory, these three scenes are vividly imprinted in my mind. I’ve read a lot of stories of cutting fruit as a symbol of love, all seemingly inspired by Yi Jun Loh’s short essay, “A Bowl of Cut Fruits is How Asian Moms Say: I Love You.” But as relatable and touching as they might be, I’m not exactly here to jump on the fruit-loving essay trend.

The Asian American family dynamic is complicated and nuanced, outfitted with two drastically different cultural norms that try to fit together as a whole. Growing up and trying to reconcile these two identities has been nothing short of difficult, and trying to see things from both perspectives only leaves me at a crossroad. Asian parents, unlike their Western counterparts, are not known for their outward displays of hugs and kisses. But as I went through elementary school and high school in the U.S., hearing parents say “I love you” as they dropped their children off, I felt resentful that my parents never did that. I yearned for those three words perhaps because I thought they were the “right” way to be loved, but perhaps also to affirm to myself that I was more than a reflection of my parent’s wishes. But I didn’t necessarily need or want to hear them say “I love you.”

Instead, I had other ways of recognizing my parents’ love. In most Asian families, fruit is a sacred promise. It should be a constant reminder that expressing love comes in many different forms, and to not hold our immigrant parents to Western standards. “Why can’t my parents say they love me?” can be loosely translated into “why can’t my parents be more accustomed to Western values,” or more bluntly, “why can’t my parents be more white?” Because they’re not. But that doesn’t mean they love us any less. Now as a college student, I wish I understood their labors of love the way I do now. Even amid the scolding and demanding, they remind me first to eat, then to get a little more sleep and finally to make sure I’m dressing in enough layers.

If you’re also afraid to tell your parents you love them, maybe cut them some fruit instead.

Sophia Ling (24C) is from Carmel, Indiana.