Let's be upfront: Thanksgiving is a problematic holiday with an origin in the oppression of Indigenous American people and culture. Art and image-making have been complicit in the erasure of this history due to the lack of historical accuracy in Pilgrim paintings or images meant to highlight the American significance of this holiday. I can immediately conjure up the Pilgrims-and-Indians-gather-round-the-table images of our grade school history textbooks and childhood tales.

We should no longer be idle in the spread of these colonialist narratives. Fortunately, what I find most hopeful in the grand scheme of art history and image-making is that we can utilize art to correct, critique and examine historical storytelling. I have found that we can use art to reflect on the positive themes of Fall Harvest, gratitude and community, without glossing over or glorifying painful histories of colonization and cultural discrimination. To facilitate that more productive use of images, not as propaganda but as modes of discussion, I have compiled a list of four artworks related to the themes and history of Thanksgiving.

1. Hartman Deetz, Wampum Belt

Harman Deetz is an exquisite beadwork artist, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and a skilled creator of Wampanoag arts. A recent Brown University Granoff Center exhibition highlighted a beautiful wampum belt created by Deetz and fellow indigenous artist, Michelle Cook, to celebrate the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), with 46 purple beads each representing one of the 46 articles. Wampum, the traditional shell beads used to make this belt, carry great significance as historical forms of currency and materials for creating jewelry, artworks and clothing, marking important political and social agreements. The detailed intentionality with which this belt is constructed, along with its subtle yet idiosyncratic color scheme make it perfect to serve as the centerpiece for Brown University’s “The Beads that Bought Manhattan: The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” exhibition.

The Wampanoag tribe is considered to be the historical tribe that interacted with the Pilgrims referenced in the traditional American Thanksgiving story. The true historical tale is that the Pilgrims did engage in a three day rejoicing feast, attended by some members of the Wampanoag tribe who had shown up to honor a mutual defense pact made previously between both groups. However, this narrative is not without sorrow, as the arrival of these settlers also meant the arrival of foreign illnesses, land destruction and the enslavement of many Indigenous Americans.

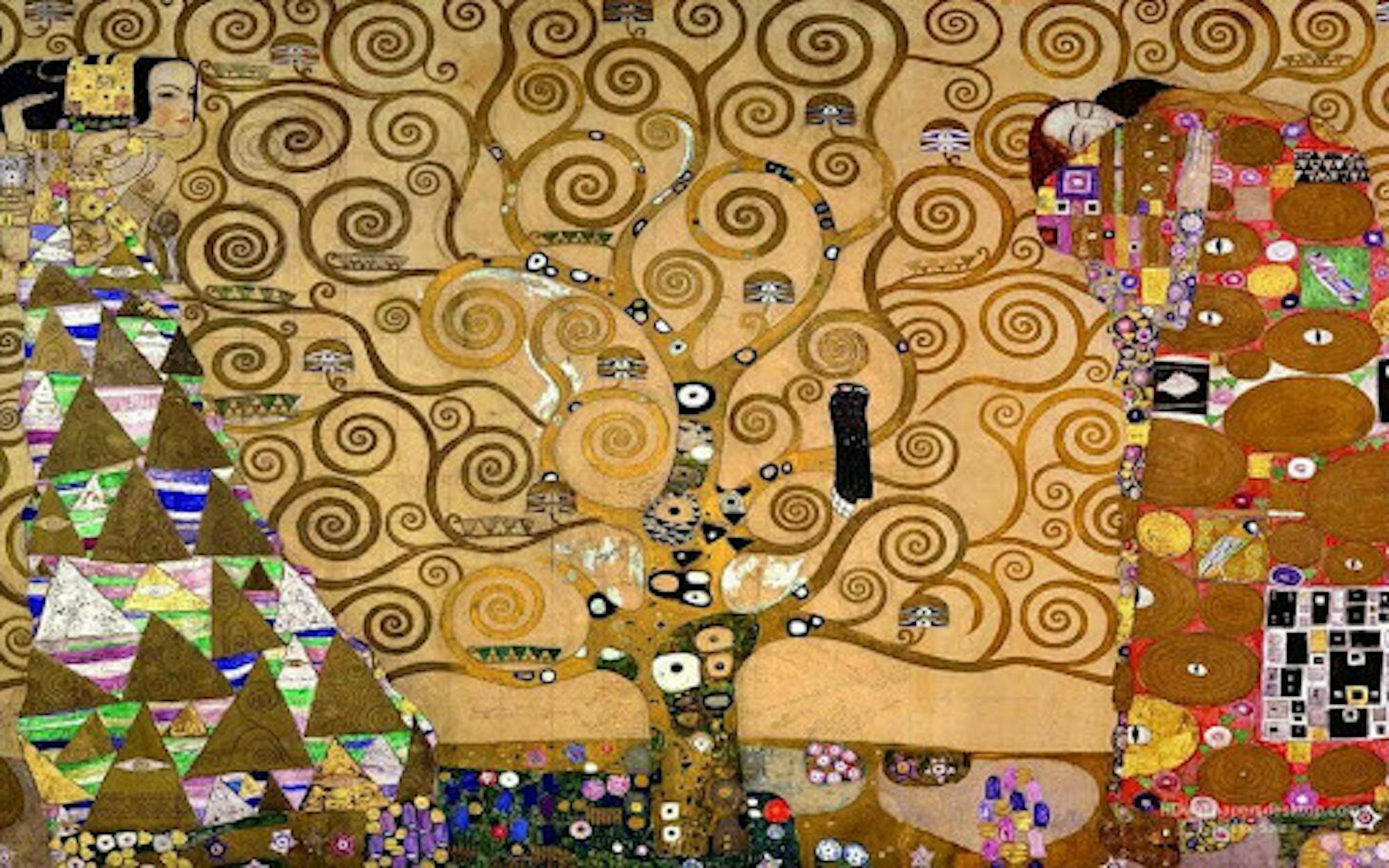

2. Gutstav Klimt, 'Tree of Life, Stoclet Frieze,' 1905

While it was not created or conceptualized by an American artist, the themes that Gustav Klimt’s “Tree of Life, Stoclet Frieze” evoke feel important for the time of Fall Harvest. The tree of life is an incredibly impactful symbol in many faiths, especially in Judaism, representing the growth of the human soul and its connection to the divine. The distinctive swirling of the golden branches with their unique undulations and disoriented spirals, as well as the short, yet grounded trunk of the tree help to reinforce the imagery of life as complex and somewhat magical; life is rooted in the earth and connects us to the sky and air.

While this painting seems to express a certain boundless hope and luxury, we are also reminded of the realities of pain and death by Klimt’s inclusion of a single blackbird just right of center. In that vein, we are encouraged to both embrace the hopeful values of gratitude for life and nature, but also balance that with our acknowledgment of the realities of pain caused by colonial oppression and the deaths of thousands brought on by colonization.

3. Wendy Red Star, 'Last Thanks,' 2006

Wendy Red Star is an absolutely iconic portrait photographer who has worked extensively with darkly humorous self-portraiture to interrogate themes of colonization and the erasure of Indigenous American history and culture. Red Star is of the Apsáalooke (Crow) lineage, and her work is deeply informed by her life on the Crow Indian Reservation. She is a master of using kitsch to analyze mainstream societal norms; she takes the most mundane yet troublesome objects, like the Wonder Bread loaf, paper feather headdresses and plastic inflatable turkey found in “The Last Thanks,” and situates them in such a combination that it forces the viewer to take pause. We begin to ask ourselves what these seemingly quotidian objects really mean and symbolize in our broader narrative and understanding of Indigenous American culture and white American narratives. These analytical artworks are vital to include in artistic canons writ large, as they challenge the vast historical inaccuracies present within our conceptions of American history and identity.

4. Norman Rockwell, 'Freedom from Want,' 1942

I would be remiss to create a Thanksgiving artwork list without including Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom from Want” painting, now pretty much synonymous with the holiday. This may possibly be the most mainstream Americana interpretation of the holiday we have seen yet. Interestingly, this artwork was created in the anti-fascist era of American resistance in World War II under Franklin Delano Roosevelt. To understand the historical context of this artwork is to understand this as a time in which American pride was deemed one of the most useful tools to fight in the war, the title even being taken from Roosevelt’s famous “Four Freedoms” speech. Rockwell was intentional in choosing the bounty and family-oriented nature of Thanksgiving to exemplify this “freedom from want.”

In seeing this imagery, hopefully when viewed in a curated selection with the aforementioned artworks, we can begin to unpack the assumption and historical issues inherent in these images. What gender roles are reinforced here? What cultures have been completely erased from this Thanksgiving narrative? What races and ethnicities do we not see present at this table (hint: all of them except for white Protestants)? We should not overlook these artworks simply because of these issues, but it is our task and responsibility to view such images with a critical and discerning eye for the narratives we are forced to see and not see. As artistic viewers and consumers of any form of media we must take a pause and ask ourselves these important questions, especially during moments of sweeping white Christian American celebration. If we approach both Thanksgiving and any art museum visit with this mindset I have hope that we can begin to unpack painful histories, acknowledge their effects in the present and work to unravel oppressive systems for the future.