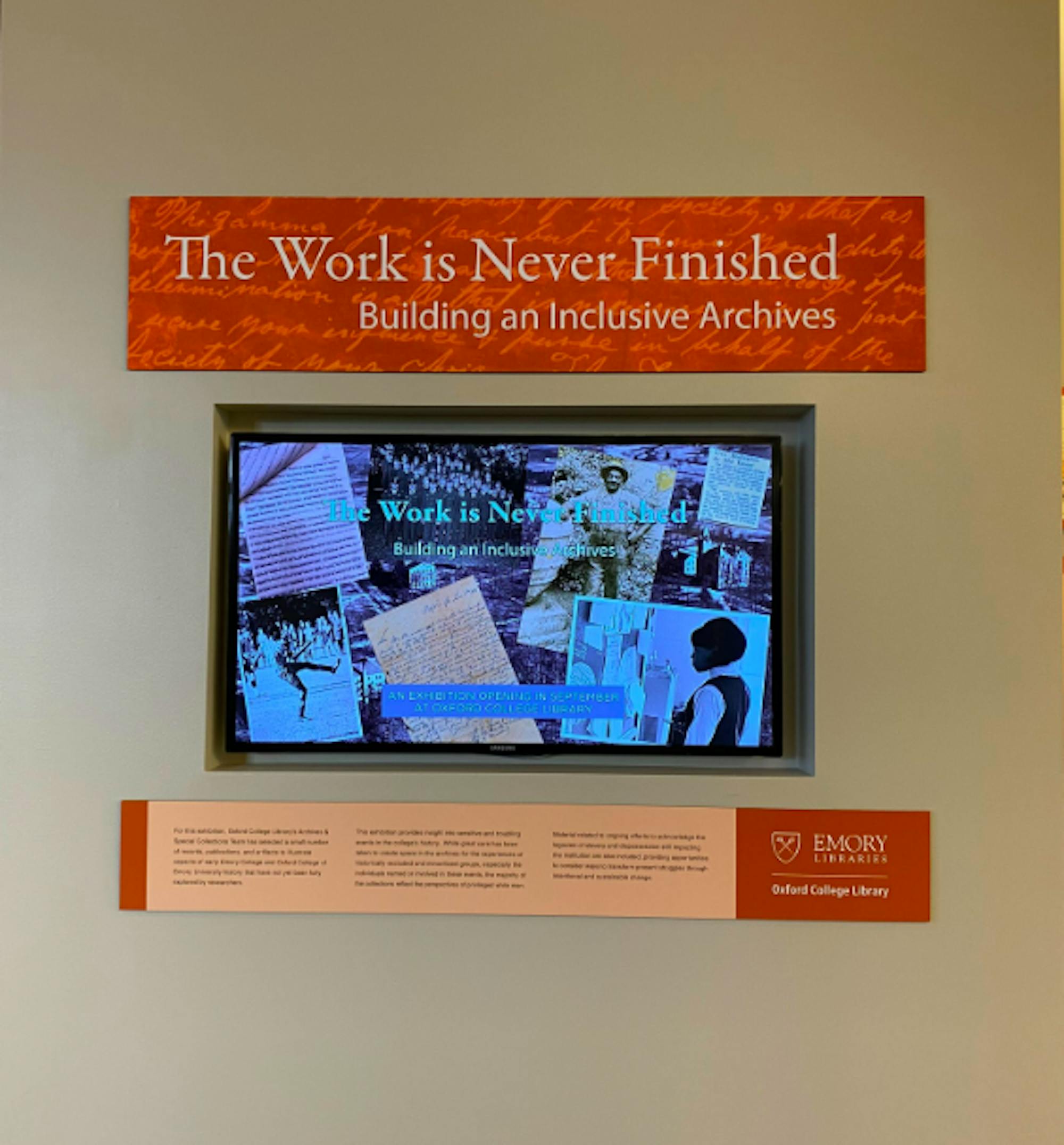

The Oxford College Library opened their new exhibition, “The Work is Never Finished: Building an Inclusive Archives,” in October. The exhibition features Emory University archives that detail the institution’s past relationship with slavery and how the Univeristy perpetuated systemic racism. These messages are conveyed through a variety of mediums, including films, photographs, news clippings and other records and publications.

Due to the content’s sensitive nature, the display warns viewers that the exhibition “includes materials related to Emory University’s past involvement in slavery and dispossession, as well as racist imagery and outdated language which could be traumatic to viewers.”

The showing is part of the University libraries’ ongoing efforts to recognize the legacy of dispossession and slavery, as well as reflect on attempts at systemic change. Other efforts include the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Library initiative to remediate harmful language in archives-finding aids.

“This is ongoing and important anti-racist work, and the Oxford College Library, collaborating with the Emory University Archives, is committed to this effort,” Archives and Special Collections Coordinator Kerry Bowden said.

Bowden continued that the exhibition is broken down into three parts.

The first, titled “Facing Injustices and Searching for Truths,” focuses on the University’s use of enslaved labor to construct buildings. It includes evidence documenting how Oxford College leaders rationalized enslavement.

The second, “Creating and Shifting Institutional Identities,” traces Oxford College’s history, from the time when only white men could enroll to the admission of the first three African American students to the establishment of the Black Student Alliance.

The final portion examines how recent events impact the present and future of the library and University.

“Every item on display is an invitation to further research,” Bowden said. “We want to continue the conversations begun at last month’s symposium … where Oxford College students shared their knowledge and experiences and encouraged us all to further investigate troubling aspects of the College’s history that are still visible today.”

Chloe Minor (23Ox) said she hopes that the library keeps the exhibition up for educational purposes, noting that “the school is in a good direction” with the display.

However, Minor indicated that she feels the University didn’t adequately publicize its troubled history prior to September’s symposium and the library showcase.

“I feel like people of color, specifically Black people, should be able to make a conscious decision about if they want to come here with all of that information,” Minor said. “Some of my friends said they wouldn’t have come here if they knew about all of this.”

The section of the exhibition detailing Kitty’s Cottage, a white shack near the edge of Oxford’s campus, particularly struck Minor. Catherine Andrew “Kitty” Boyd lived in these quarters as an enslaved person under ownership of Methodist bishop James Osgood Andrew. Records state that Catherine decided to stay in Georgia after Andrew freed her.

Minor was not the only student with such criticisms. Oxford College Black Student Alliance President Sarah Bekele (22Ox) believes the exhibit glossed over important details by focusing more on the historical context of the time than the University’s specific actions.

Bekele added that she thinks the exhibition should have been more visible and Oxford should have been more vocal about it as she doesn’t think many students have seen the display.

“That’s a problem with a lot of the things on this campus surrounding minority groups,” Bekele said. “It’s not talked about as much as it should be and that’s a recurring theme.”

Bekele said she plans to have a conversation with Oxford College Dean of Campus Life Joseph Moon about this along with other ways in which Emory discusses slavery.

Despite these shortcomings, Bowden said the exhibition made an effort to amplify Black stories. For instance, the second section of the exhibition features the first Black students enrolled at Oxford College: Tony Gibson (71Ox, 73C), John Hammonds (71Ox, 73C) and Ann Slaughter (71Ox, 73C). Bowden added that they served as student body leaders, with two being elected to the Honor Council and one participating in ROTC.

The exhibit highlighted many other individuals who impacted the University.

Billy Mitchell, an Oxford employee whose grandparents were enslaved by a family connected with Emory, has often been tokenized despite his significant impact on Oxford College. Bowden said, “Here we’re able to present an interview with Mr. Mitchell where he describes his experiences of Oxford in his own words.”

Slaughter, the first Black woman to graduate from Oxford College, was also featured in the exhibition. Slaughter’s experiences were displayed via candid films depicting her and her classmates during their years at Oxford.

The exhibition also highlighted questions throughout the sections, inviting the viewers to reflect on the content, Bowden said.

“[The exhibitionists] made an intentional effort to contextualize the items in terms of whose perspectives and experiences are and aren’t represented in our collections,” Bowden said. “Viewers are asked to consider the power dynamics at work in the process of preserving institutional history, particularly how those practices have resulted in absences and skewed representations of Blackness at Oxford College.”