The Victorian house at the corner of Peeples Street and Lucile Avenue looks like an ode to Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority with its salmon and sage facade. A bay window with a tall spire juts out in greeting like a lighthouse, while green stairs lead up to a pink and green checkered porch.

This Victorian is the Hammonds House Museum, formerly the home of Dr. Otis Thrash “O.T.” Hammonds, an Atlanta physician and arts patron. After Hammonds’ death in 1985, his private collection of African diasporic art was purchased by Fulton County to form the museum’s permanent collection. The collection has since expanded from 250 to 450 works.

As an art history major concentrating in ancient Roman art, I rarely get to engage with contemporary art unless it connects to Rome. I was excited to be invited to review “Exhibiting Culture: Highlights from the Hammonds House Museum Collection,” which featured works hand-picked by Executive Director and Chief Curator Karen Comer Lowe. When I arrived at noon on Aug. 6, the opening day, I was the only guest. A handful of guests filtered through during my visit, but the museum was never crowded. After being warmly welcomed by a staff member at the entryway, I started exploring each room.

The ground floor had been transformed from a house to standard white-walled gallery space to push focus on the art while large windows let in waves of sunlight. I didn’t notice any clear intent behind the layout aside from art being grouped by artist. Neither periods nor movements for the displayed works were named, though some labels included QR codes which linked an article or YouTube video about the work or artist.

The QR code labels seemed innovative at first, but I soon quit scanning them, as I didn’t feel comfortable enough to play a video out loud in a public space. The codes also presented an accessibility issue; some guests may not have a device capable of scanning the codes, or see well enough to read the device screen.

A highlight of the front rooms included a portrait on a sterling silver plate by Charles White.

Museums always surprise me — rounding each corner into a new room of art is eternally thrilling. Rarely is the surprise as unpleasant as when I entered the late Hammonds’ dining room.

I was immediately greeted by a table set for four, which occupied most of the room and was framed by a set of bay windows. The contrast between the cramped dining room and open, airy front rooms was stark. Many pieces were unlabeled, whereas in other rooms, all pieces were labeled and some were presented in more traditional museum plexiglass cases.

One word came to mind and wouldn’t leave me for the rest of my visit: “Wunderkammer,” literally “wonder cabinet” or more directly, cabinet of curiosities. As part of my introductory art history courses, we learned that it was common practice in the 18th and 19th centuries for wealthy white men to display art and artifacts for entertainment, without regard for the context or original culture of their looted items. Museum conservation is a difficult subject — there are many ways to display an item so it endures for years to come while including important context — but most curators and conservationists agree a level of respect and care should be a given.

I did not get a sense of respect nor care for these items. I worry about their safety and preservation if guests are able to come in contact with them, either accidentally or purposefully. In the dining room, the layout was reminiscent of these careless and insensitive “Wunderkammer.” I was an interloper, a nosy guest sneaking around at a party.

While I don’t question Lowe’s education, experience or expertise, I nevertheless made a point to inquire after the display of the older African objects and express my concern as a fellow art historian.

Lowe seemed to brush this off. “The museum right now is in transition,” she said, referencing the fact that she started her position as executive director and chief curator June 1. The Hammonds House reopened to the public last July after a brief closure due to COVID-19.

“[The dining room] has always been set up in that way,” Lowe continued, “with some of the original furniture and artifacts that belong to the doctor.”

Lowe further explained that she was, “in the middle of refreshing that room. And there will be a lot more context added to some of the items there. It just hasn't been done before.”

Among the unlabeled objects in the room, one in particular sat on the hearth, with a portrait by Hudson River School artist Robert S. Duncanson nearby. When I expressed hesitancy at scanning the painting’s QR code to avoid getting too close to the object, Lowe assured me, “Don’t worry about it, it’s fine.”

The exhibition would have benefited greatly from simple rearrangement to maximize the available space. If certain rooms had been switched around and merged, with objects not ready for display kept in storage, I would’ve enjoyed my visit more. For example, I was directed by staff to a back section of the house which appeared to be a highlight of the galleries several times. However, the area leading that way was very uninviting; the flooring was linoleum versus original hardwood, and the lighting was harsh fluorescent versus the soft natural light that flooded the rest of the house. I even saw several “staff only” signs through the first doorway, but no signs granting me permission to go that way, so I forgot I was allowed back there.

Like the dining room, this backroom held a drastic shift in atmosphere. Once again, I felt like I shouldn’t have been there, but this time I was peering behind the curtain. The few art pieces on display, gorgeous pieces of contemporary mixed media, were displayed like afterthoughts. Projected archival footage of some of the artists in an adjoining room was similarly displayed.

After viewing some of the archival footage, I followed a museum sign on a table at the end of a hallway out of curiosity. Another hallway appeared to my left. I ended up totally alone, the faint sound of soul music piping in through an event speaker in an unused room.

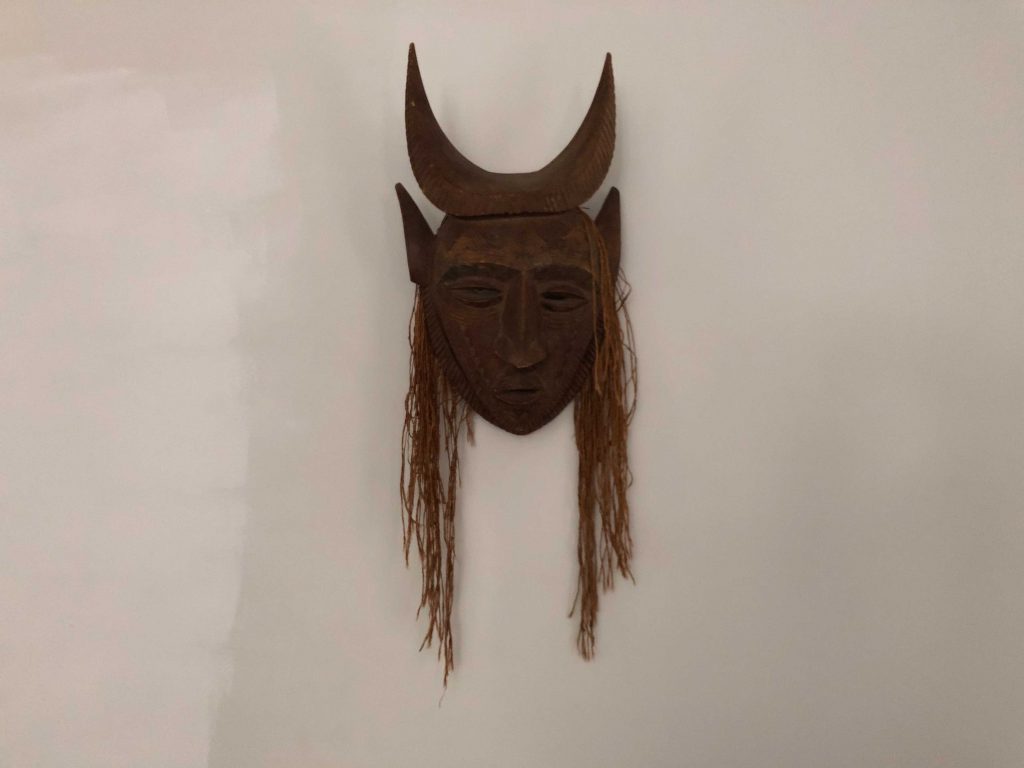

The next room appeared to be Hammonds’ former formal living room, complete with aging carpet and a mid-century fireplace. This, however, was not what I noticed first. To my shock and horror, I found myself facing African masks contemporary with other unlabeled and unprotected objects. I recognized these objects as part of Dr. Hammonds’ private collection from my conversation with Lowe where she’d mentioned the masks in response to my concerns about the unlabeled objects in the dining room.

|

|

|

African masks dating from c. AD 1700-1900 displayed unlabeled in the former home of Dr. O.T. Hammonds. (Emory Wheel/Jada Chambers, Copy Editor)

I wanted to enjoy my visit to the Hammonds House. I was excited to add more contemporary artists of the African diaspora to my visual repertoire and engage in contemporary art culture. I ended up unsettled and conflicted, awed by the gorgeous art yet upset by the artifacts’ mistreatment.

I do not believe poor curatorial decisions speak to Lowe’s capability or experience. Lowe previously managed and curated at the Chastain Arts Center for a decade prior to her position at the Hammonds House and has worked in her field for over 20 years.

Small specialized museums such as the Hammonds House are often horrendously underfunded, while their affluent counterparts can access more resources. Rather than disparage a small museum with massive potential, I suggest at least paying a visit, but I encourage visiting with the utmost respect for the space and the courage to speak up should other guests be less informed on museum etiquette.