The nomination of Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe of New Mexico, to be the first Indigenous head of the Interior Department, passed out of committee to the full Senate on March 5.

A significant step for Native American representation and rights, Haaland’s path was paved by many women Indigenous activists highlighted in a webinar hosted by the James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference on March 4. Forty-two people attended the virtual event out of 61 registered.

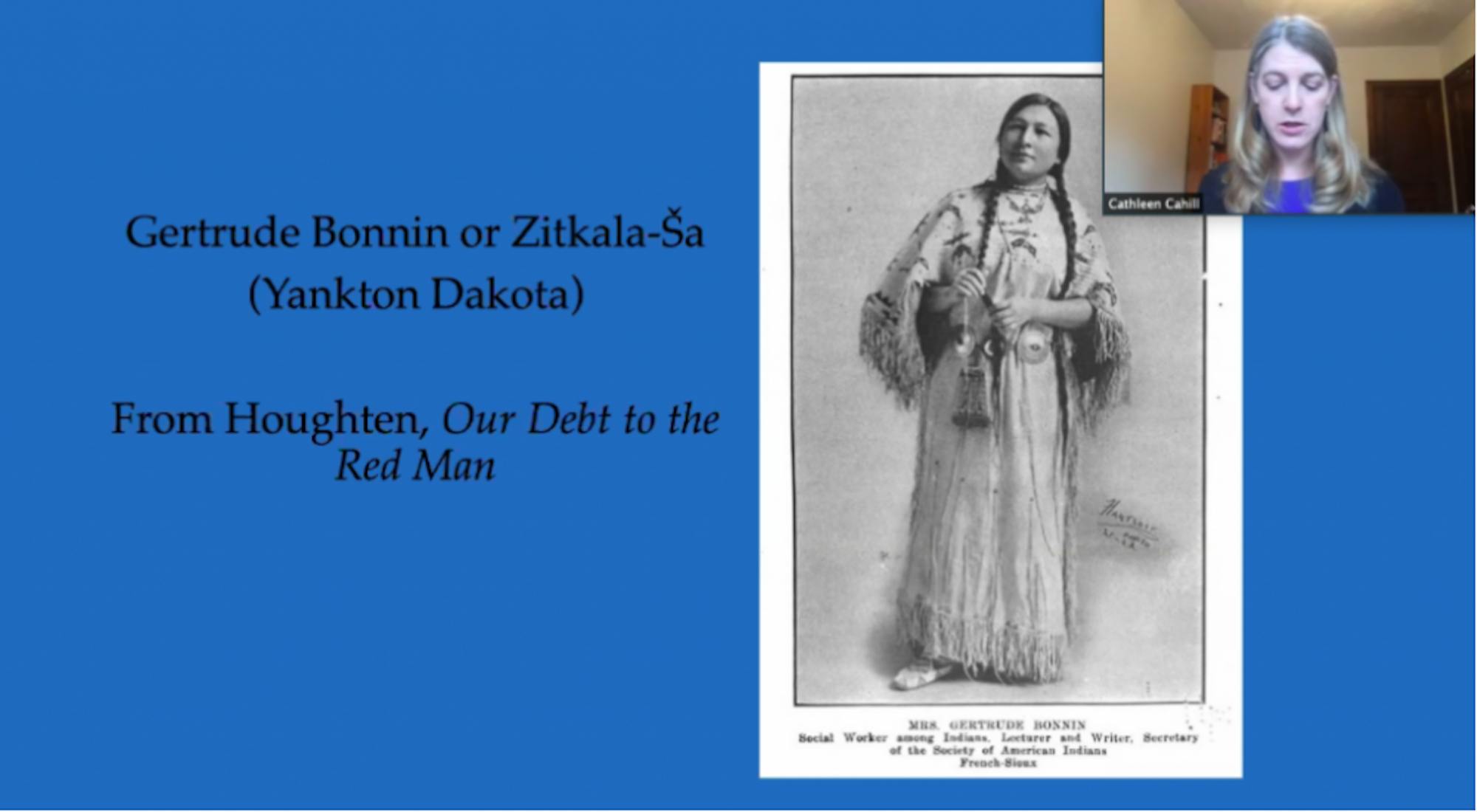

The event featured Pennsylvania State University Associate Professor of History Cathleen Cahill. Like her presentation, she has published multiple books that use primary texts and images to tell the story of Indigenous women and voting.

Associate Dean of Admission and member of Tohono O’odham Nation Beth Jennifer Michel (12PH) began the webinar by acknowledging the Muskogee Creek land that the University sits on.

“Emory University was founded in 1836 during a period of sustained oppression, land disposition and forced removals of Muskogee Creek and Cherokee people from Georgia and the southeast,” Michel said.

Cahill discussed the “suffrage pioneers,” including well-known white suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott. She noted that the 19th Amendment these women advocated for did not enfranchise Indigenous women or, in practice, many women of color.

When first brokering treaties with Native American tribes, the U.S. government saw tribal land as sovereign and Indigenous people were citizens of their tribal areas. After the Civil War, however, the U.S. government severed diplomatic relations with tribal governments and implemented a “policy of assimilation.”

According to Cahill, the government stopped acknowledging native citizenship and deemed Indigenous individuals as “legal wards of the government who were not yet fit for U.S. citizenship.” Native Americans were neither seen as citizens of the U.S. or of their own sovereign land.

“Wards of the government” also applied to children, prisoners and developmentally disabled people. Cahill said a modern example of a “ward of the government” would include pop star Britney Spears’ conservatorship, which has garnered recent media attention.

Cahill discussed activists for women’s and Native voting rights, including Marie L. Bottineau Baldwin, a member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa and Metis tribes, Laura Cornelius Kellogg of the Wisconsin Oneida tribe and Gertrude Bonnin or Zitkala-Ša of the French-Sioux.

All three women were active members in the Society of American Indians and worked for the Indian Service.

Baldwin was one of the first Indigenous women to get a law degree in 1913. She and the other Indigenous feminists called for an appreciation of American Indian art forms, fought against the “squaw” stereotype and argued that Indigenous cultures treated women better than white women in society. In her essay, “The Need of a Change in the Legal Status of North American Indian in the United States,” Baldwin argued on behalf of native rights.

“This thesis was essentially a course on native history and native law,” Cahill said. “She basically traces the legal changes through which first Europeans and then Americans in the United States had come to believe that tribes were not sovereigns, but wards of the government.”

While most white women mark 1920 as the year women received the right to vote, most Indigenous women were not granted the same right until 1924, when Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act. The legislation granted American citizenship to indigenous people and ended the “wards of government” policy.

The advocacy of Baldwin, Kellogg and Bonnin played an important role in the legislation’s passage, according to Cahill. However, many Indigenous people at the time did not support the legislation, believing that receiving U.S. citizenship ignored the sovereignty and land rights entitled to tribes.

However, citizenship meant voting rights. In 1926, Bonnin established the National Council of American Indians, which worked to get Native Americans registered to vote. The organization’s motto was, “Help Indians help themselves.”

Two years later, Republican presidential candidate Herbert Hoover chose U.S. Senator Charles Curtis, a member of the Kaw Nation, as his vice presidential candidate.

“A number of native people are really thrilled by this information,” Cahill said. “People attend his rallies, newspapers report that they’re registering to vote for him, native women are participating in Republican campaign structure.”

Hoover and Curtis would go on to win the election, making Curtis the first Native American and first person of color to serve as vice president. But the success obscured a larger oppressive trend, according to Cahill.

Cahill explained that attention on Indigenous enfranchisement meant that states installed voter suppression tactics targeted at indigenous populations. Many states quickly adopted laws similar to Jim Crow voting laws, including poll taxes and literacy tests.

Other states, including Arizona and New Mexico, passed legislation that any person who lived on a reservation could not vote.

“It would still take decades to address disenfranchisement and native people continue to be disenfranchised today,” Cahill said. “Most of our discussions of native voting history have focused on men … But, if we shift our gaze toward the turn of the century we are reminded native women are also involved in these debates.”

The University will hold several more Indigenous-based events this month, including a public reading by national Poet Laureate Joy Harjo of the Muscogee Nation on March 20 and the panel “Freedmen Claims in Relation to McGirt vs. Oklahoma” on March 30.