The capacity that words have to move the soul is extraordinary. Something as simple as a few letters put together can cause a stir of emotion in the listener, an understanding between people and an acknowledgment of our own existence. Words can claim space and tear it apart. Words can create peace and start wars. If anybody knows this great power of words, it is current United States Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, a performer and writer known for using her poetry to address Indigenous identities and presence.

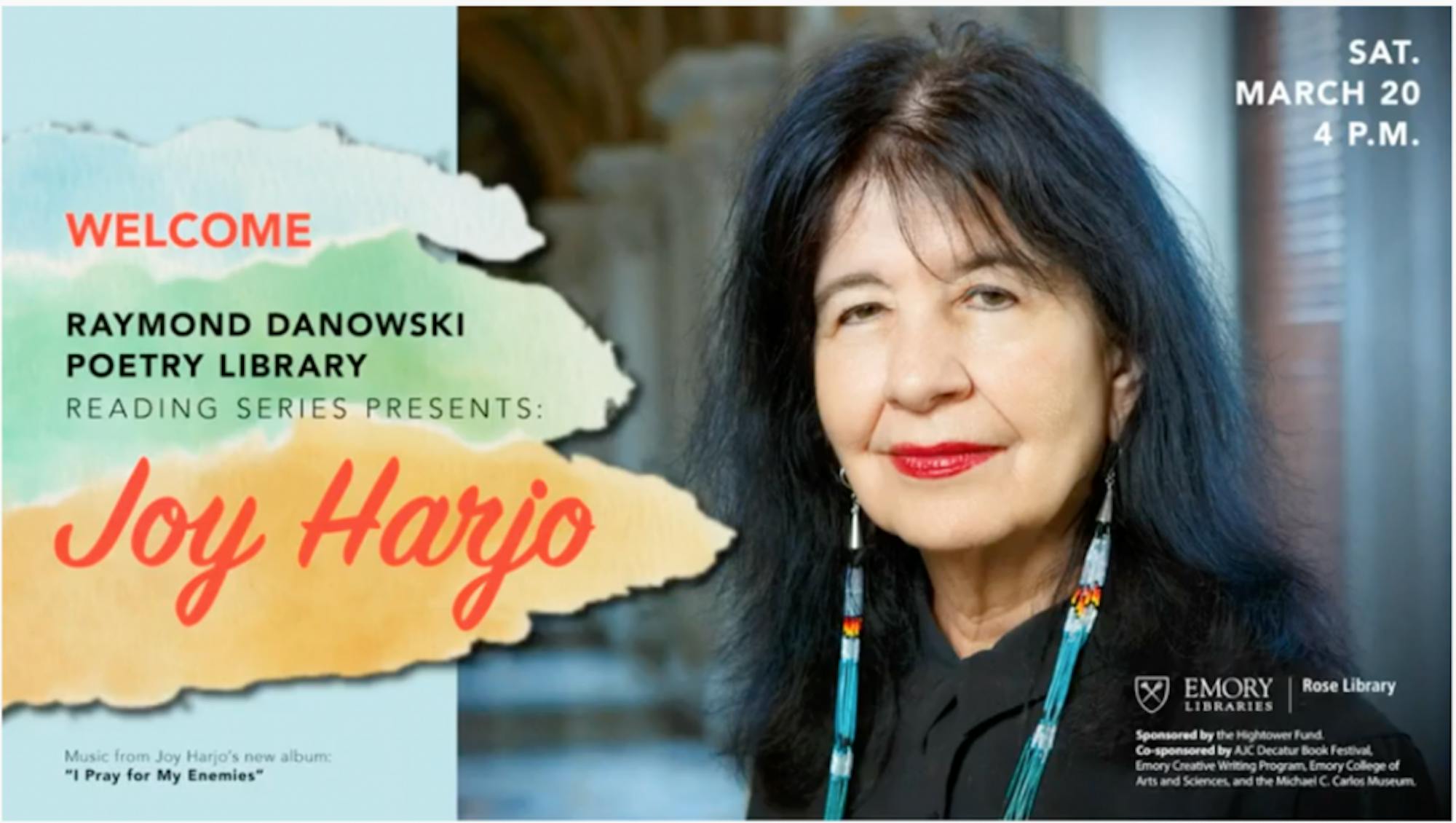

On March 20, Harjo read a selection of her poems during a live-streamed event hosted by the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. This reading was part of the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library Reading Series, one of the longest-running events of its kind, which celebrates the powerful place poetry holds at Emory. The background music of the livestream’s welcome screen, which was sampled from Harjo’s new musical album “I Pray for My Enemies,” perfectly described this creative, emotional poetry experience, as she sang, “The door to the mind should only open from the heart.”

Harjo is the 23rd poet laureate of the United States and has held that title for an amazing three terms since June 2019. She is also the author of nine books, a musician, an Oklahoma Writers Hall of Famer and the winner of the 2017 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize.

Harjo’s presence at Emory carries a deeper meaning as well because she is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and belongs to Hickory Ground, and Emory was founded on the historic lands of the Muscogee people. Land acquisition often has a dark history; the U.S. acquired land from the Muscogee Nation through an 1821 treaty, which pushed many Indigenous Americans to move from Georgia to Alabama. In Alabama, they were forcibly removed to Oklahoma via the Trail of Tears. Craig Womack, author and associate professor of English at Emory, honored this history by beginning the event with a land acknowledgement and singing a resonating Muscogee prayer. He implored the audience to acknowledge Emory’s responsibility to this Muscogee land, and he also took this time to address the lack of representation of Atlanta-based Indigenous and Black Americans in the Emory student body. Womack chose to discuss these ongoing issues of dislocation because they mirror points raised by Harjo’s poetry. Harjo engages with ideas of removal, loss and resilience, empowering readers to heal and situate the voice and culture of Indigenous Americans in the broad American narrative. The profound ways that Womack and Harjo use their platforms to raise awareness of land displacement issues and Indigenous American history is moving.

Mandy Suhr-Sytsma, director of the Emory Writing Center and senior lecturer of English, also introduced Harjo. Suhr-Sytsma described the modes by which Harjo’s poems position us between the past and the present, helping us to understand historical consequences and identify the meaningful reparative actions we can take in the present. Suhr-Sytsma encouraged viewers to join Harjo in honoring this land and the power of poets.

After the speakers’ introductions, Harjo began reading. Despite the lack of physical imagery, Harjo painted an entire world through her poems. It would feel disrespectful to quote mere bits or pieces of her works when she created such complete, complex narratives out of her poetry. Line by line, she built a house of words that described the beloved Earth and the ways the Muscogee people have fostered the health of the land. While her sentences and word choice may be relatively simple, her style is complicated by the powerful metaphors and native histories she utilizes.

Before reading each poem, Harjo briefly described why she wrote it and the meaning it carries for her. For example, before reading “Speaking Tree,” she spoke about her friend and colleague Sandra Cisneros, a Chicana writer, whose quote, “I had a beautiful dream I was dancing with a tree,” is the first line of Harjo’s poem. Learning the background of these writings enriched the audience's listening experience and opened the door to an honest, creative retelling of the past.

Harjo also read a newly-written poem entitled “Somewhere” in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, a racist terror act in which white residents attacked Black residents and businesses in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She said her poetry “stands naked in the truth of racism,” releasing the pain and reality of that history. Her use of words to not only recognize the pain of her ancestors but also the struggles of fellow minorities was a beautiful and pertinent example of how marginalized communities are stronger when they stand together. This was not an oppression competition, but a unified cognizance of shared struggles.

One commentator on the YouTube livestream acutely described their feelings at the end of the event, stating that there was “so much beauty here … too much to take it in easily.” There are so many layers to Harjo’s words that one could listen to them three times over and still take a different lesson from them each time, latching onto new imagery and realizing creative connections between the past and present.