Lately, I have been feeling as though classical art has become overrated. From dramatic TikTok recreations of famous artworks to trendy tattoos of Michelangelo’s “David” and the “Creation of Adam,” our definition of classical art stems from later interpretations of it and gets treated as a homogenous, unchanging canon. Since hearing this year’s Nix Mann Endowed Lecture, “The Shifting Shape of Classical Art,” I’ve come to realize classical art is diverse and relevant, and it must be included in conversations surrounding power, value and equity.

On Jan. 31, Professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge and Byvanck Chair of Classical Archaeology at the University of Leiden Caroline Vout examined the journey, transformation and revival of classical art forms throughout different artistic periods.

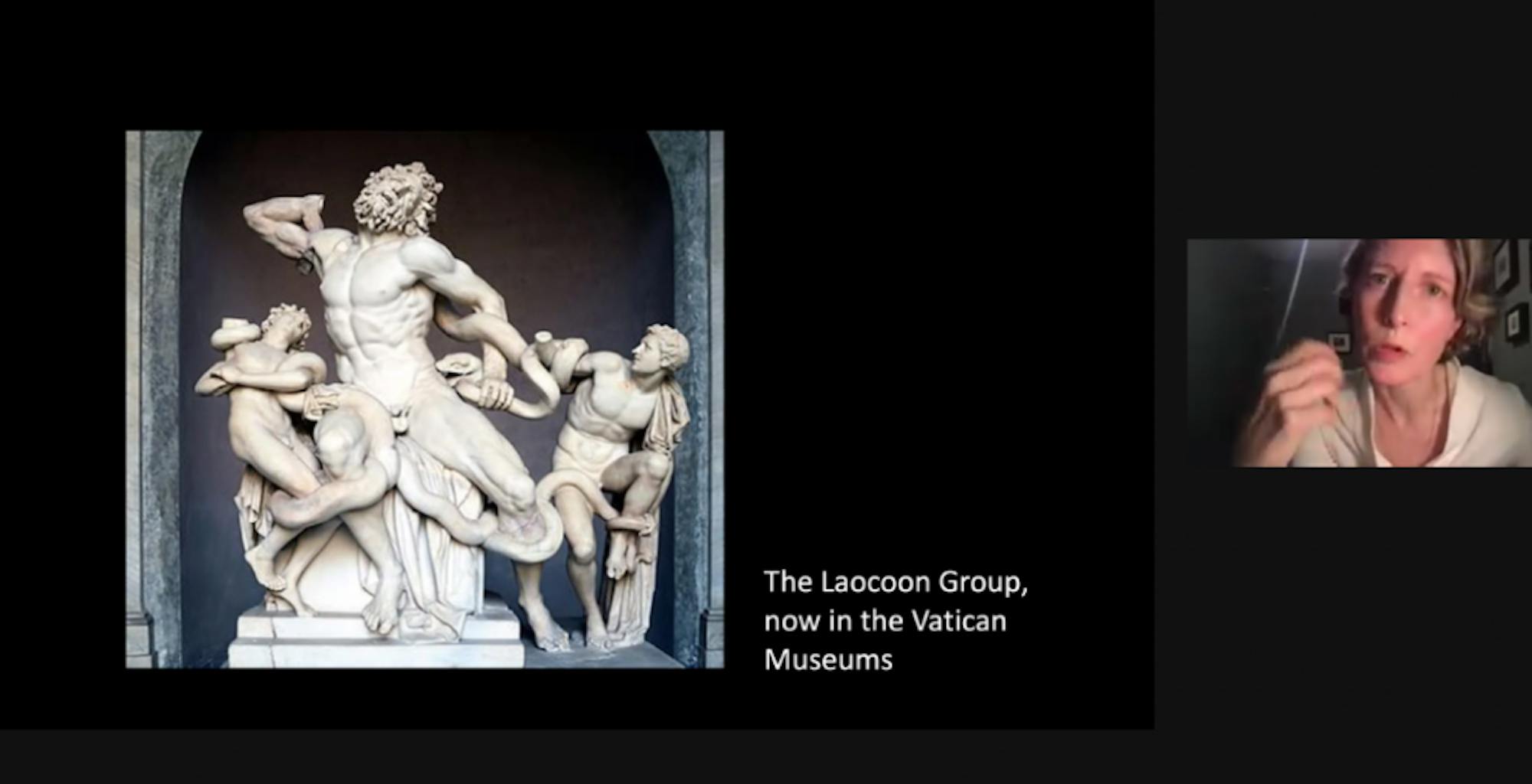

In the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., early classical Greek statues lived in temples and sanctuaries, not art galleries or museums. Later, when the Roman empire expanded, their triumphal military processions focused chiefly on carrying Greek artworks into Roman cities, showing the bounty they had won. The Romans had a love affair with Greek art, and the preferences of Rome’s generals began to establish the art history canon we see today. Their decisions on which art to imitate and which to leave behind established that canon. Vout believes Greek art gained prominence in this process, as more and more Greek sculptures continued to inspire the Romans.

As more classical sculpture has been discovered, new technologies like plaster casts have allowed for them to be easily copied, transported and disseminated across the globe, developing a universal classicizing language and Eurocentric view of art. Eventually, even Thomas Jefferson made a list of casts he wanted at Monticello. In the 19th century, photography became a way to study these sculptures as well, allowing early art connoisseurs to examine the details from the comfort of their own homes.

As Vout explained, men of the 1800s immersed themselves in classical art’s performative power and idealized forms, as the Renaissance thinkers had begun to do and the Romans before them. This use of art acquisition and the ranking of classical art above others to assert power has been one of the greatest issues faced in the art world today. There is a lack of equity that comes with such inherently sexist, racist and classist definitions of value, especially in the art market and in museums, that has favored European white male artists and classical artworks over other artists and artworks.

The lack of diverse representation in classical was another critical issue Vout discussed at length; different body types, races and geographical areas are often left out of the art we associate with classical Greco-Roman styles. Classical art actually embodies a wide variety of artworks created from areas all across Europe and the Mediterranean that feature a diverse array of subjects. Vout’s choice of artworks exemplified this diversity as she included works from Egypt, works depicting emaciated children or curvy women and sculptures with their vibrant traces of pigment.

Despite this diverse range, art historians — ranging from Roman conquerors to British art critics and historians — have controlled the narrative of classical art. Sculptures with “ugly” body types as defined by art historians were often left out of the collective appreciation of classical sculpture. Vout gave another example of a Greek sculpture of a Black youth in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, United Kingdom, that was placed by the bathrooms rather than in the classical art galleries. Classical art and its use and treatment over time has a lot to teach us. We are forced to examine what is and what isn’t included in the art historical canon, what is valued by the art world and how it reflects on us as a collective society.

Vout’s lecture and the in-depth visual analyses of the works interwoven throughout helped the audience examine new concepts and valuable questions raised by classical art. That being said, this lecture series may not be for everyone. Vout used a fair amount of art historical jargon and assumed a certain amount of background knowledge from listeners. While not presenting the most accessible lecture, Vout made some relevant points about classical art and equity. Even if I didn’t necessarily retain all the facts and specifics, Vout revealed important areas of reflection and discussion.

One of the most interesting and overarching observations Vout made was that the Greco-Roman classical statues placed in the top tier of art say a lot about us as a society and about what we value. The process by which classical sculpture accrued value and artistic merit was fascinating and revealed much about the human tendency to compare, rank and prioritize. Through relevant lectures like these, conversations about artistic comparison, assumption of Eurocentric art historical values and the choices of museum curators can really begin to flourish.