Courtesy wikimedia Commons.

Linda McCauley, dean of the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, attended a meeting of deans from around the country in Washington, D.C. as part of a White House initiative to protect communities from the impacts of climate change.

McCauley was invited by Barack Obama's administration as a representative of the School of Nursing to the April 9 meeting of 30 medical, public health and nursing schools from around the country.

The meeting was part of Obama's National Public Health Week, which was announced with a series of actions “to set us on track to better understand, communicate and reduce the health impacts of climate change on our communities,” according to an April 7 White House press release.

McCauley, the only Emory representative at the meeting, said that although “there’s a lot of activity in the White House about climate change in general, they had never [until this meeting] pulled a group to talk about the consequences.”

Since almost all of those present at the meeting were educators, the meeting focused on the health workforce of the future, and more specifically on methods to ensure “students [are] being given the information and the tools they need to understand and address the multiple health problems associated with climate change,” McCauley said.

At the meeting, the coalition signed a commitment to ensure that the next generation of health professionals will be trained to effectively address the health impacts of climate change, according to the White House press release.

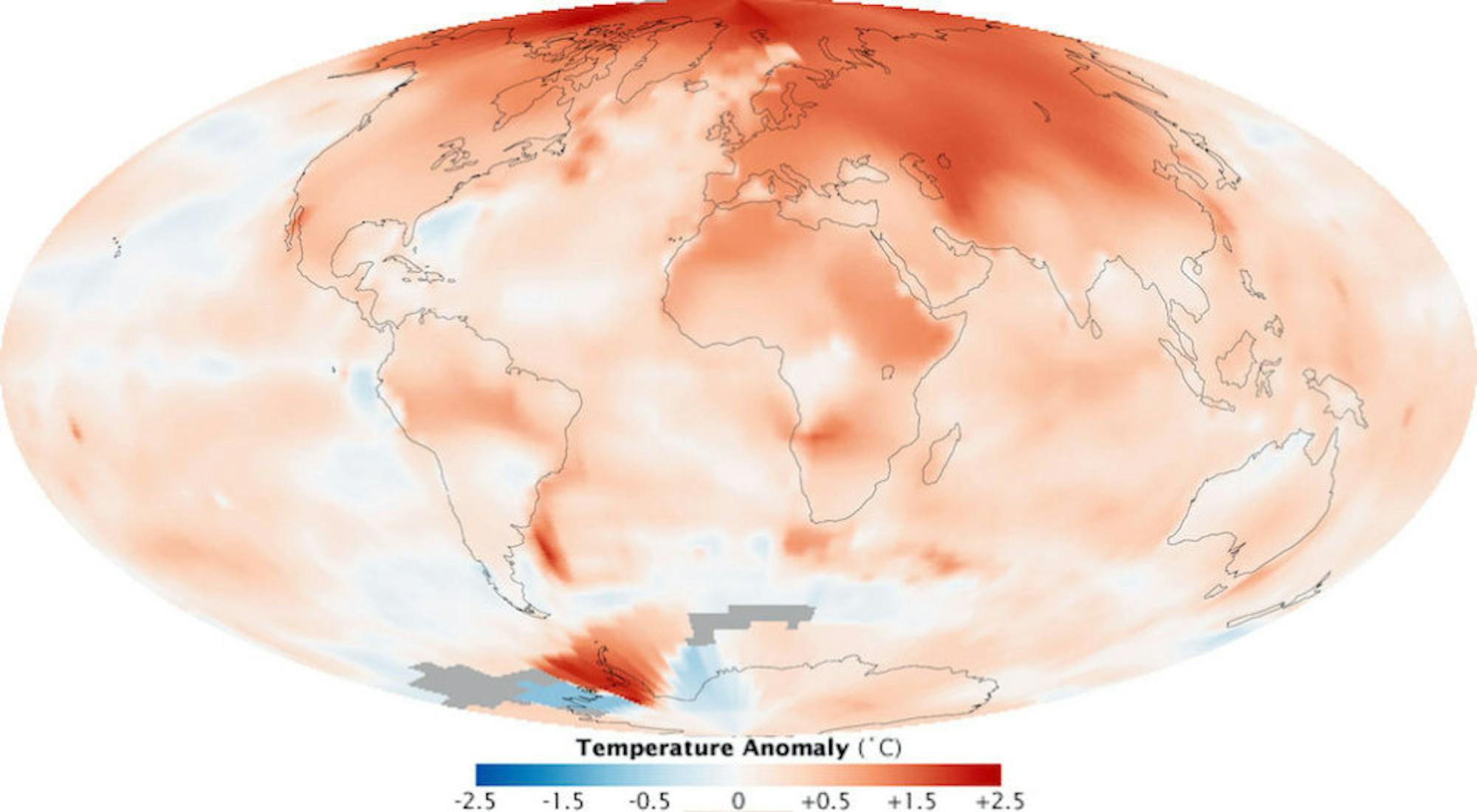

“It’s just a commitment of recognizing climate change is happening and that the events that we’re seeing are going to escalate,” McCauley said. She added that, even if we reduced our carbon footprint and our green house gas emissions dramatically tomorrow, it would still take years to reverse the warming that the climate has already experienced.

Further explaining the commitment she and the other deans made at the meeting, McCauley said they are committing themselves to work with the the Obama administration and among respective universities “to come up with ways to make sure that students are exposed to the knowledge that they need and that professors and universities across not just the United States but globally have the tool kits of information to teach students.”

Overall, McCauley said that she thought the event was “extremely beneficial.”

“Many ideas were shared about how to ensure that college students, particularly health professional students, are exposed to this extremely important information,” McCauley said. She added that those who attended the meeting also discussed the development of a “tool kit” of learning activities that could be shared with educators across the U.S. to guide them in integrating climate change and health content into their courses.

McCauley said she discussed the initiative Climate@Emory as an example of collaboration between schools of different disciplines giving students the information and education that they need. Climate@Emory is an Academic Learning Community that faculty and staff launched in January 2014 to foster collaboration on topics associated with a changing climate, including human health problems, according to the Climate@Emory website.

Health problems discussed in the meeting included both those which affect people who actively work against some of the effects of climate change and direct health affects of climate change. Some people mentioned and direct effects were: people who must work in hot climates and are thus susceptible to heat stress, such as firefighters who have to fight forest fires; air pollution and its effect on respiratory and cardiovascular health; and disaster preparedness and mental health diseases associated with the trauma of disasters, according to McCauley.

She also cited that specific diseases' prevalence is affected by climate change, including “things like lyme disease and malaria, where the distribution of those diseases are changing globally because of changes in temperature.”

Asked why she was chosen for the event, McCauley said it was likely due to her position on the Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine, a group of cross-sector experts at the Institute of Medicine that meets to explore emerging issues relevant to the environment and human health.

This “90-minute initial meeting,” according to McCauley, served as a precursor to the White House Climate Change and Health Summit which will take place later this summer, according to the release. The all-day summit will also likely include experts and educators who will present the curriculum model discussed at the meeting, according to McCauley.

College senior Aubrey Tingler wrote in an email to the Wheel that, although she’s glad the White House is initiating discussions on climate change, she thinks it would have been more appropriate if they had invited faculty other than deans, who she says are “not necessarily most involved with climate issues at universities, especially since many deans do more administrative than ‘on the ground’ work.”

Tingler cited Daniel Rochberg, a instructor in the Department of Environmental Sciences who, according to Tingler, has a strong climate policy background with the federal government and actively teaches about these issues at Emory.

Of Emory’s efforts to educate students on climate change, Tingler wrote that Emory could definitely do more, but "Climate@Emory has a lot of potential to further educate students about climate change."

“[Climate@Emory is] doing some really interesting work with integrating climate studies across disciplines here and making climate change awareness and action a more prevalent part of Emory['s] culture,” Tingler added.