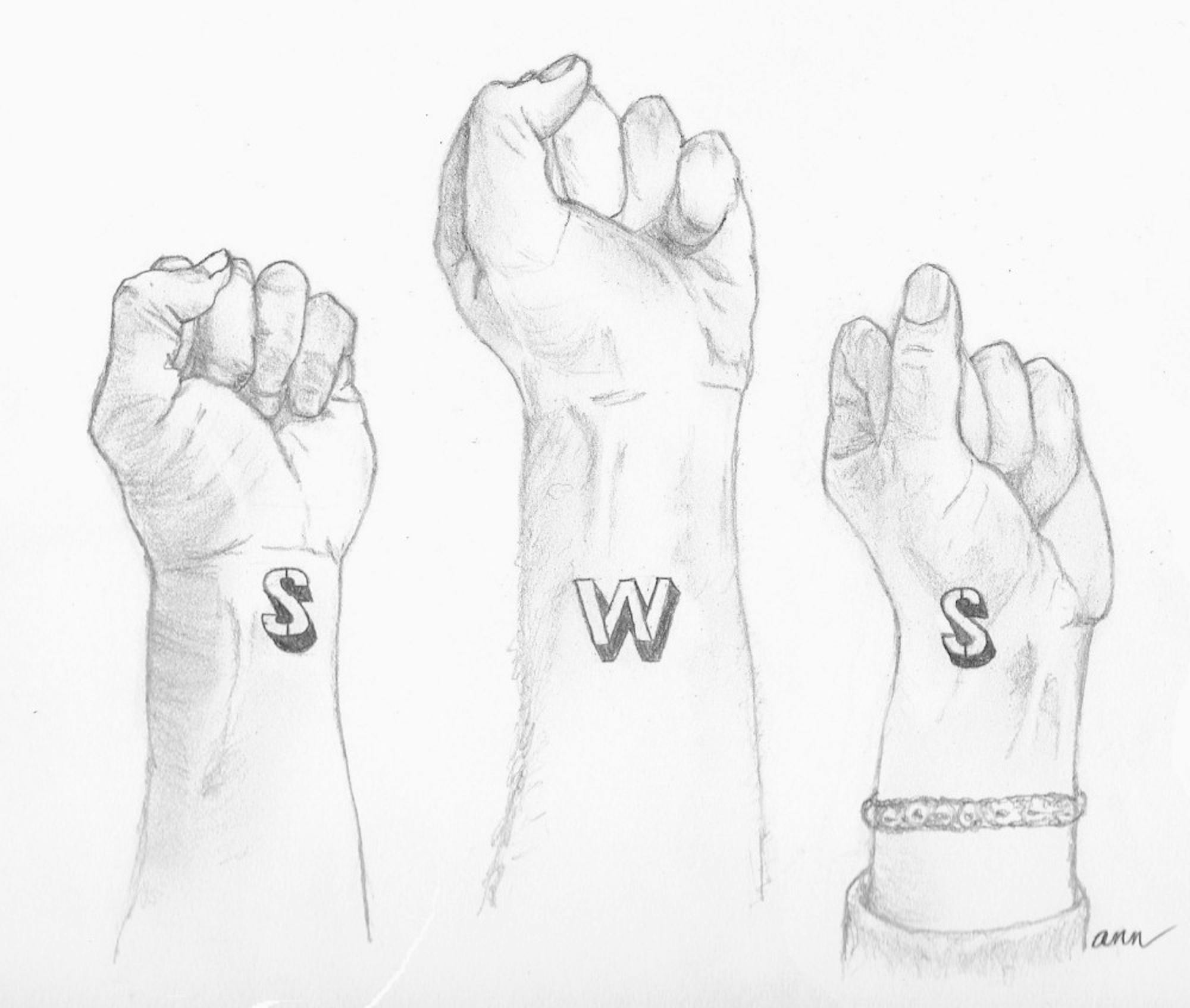

Comic by Anna Mayrand

In 2013, Emory University’s Committee on Class and Labor, tasked with exploring how class functions on campus, recommended that the University should “seek to reduce significant differences between the circumstances of Emory’s staff and circumstances of contracted workers.” It is my firm belief that if Emory is truly committed to applying knowledge in the service of humanity, then it must begin to confront the vast disparities between subcontracted workers and those workers deemed worthy of direct employment.

In light of the impending expiration of the contract Emory has with the company that manages its dining operations, Sodexo, the question of renewal is being discussed. If one believes the statements made by the Sodexo Group, then it actually is the “world leader in Quality of Life services.” Unfortunately, however, an examination of Sodexo’s actions tells a very different story. Across the 80 countries in which Sodexo Group operates, “quality of life services” include constructing and managing private prisons (as “Sodexo Justice Services”) and threatening workers who attempt to unionize or blow the whistle following human rights violations.

Several human rights reports unambiguously document Sodexo abuses. To name just one, the Transafrica Forum report found that “[t]he business model Sodexo employs keeps workers poor and locks their communities into seemingly endless cycles of poverty.” Sodexo is known to cut hours and their policies exclude a large percentage of workers from benefit eligibility — in Atlanta they don’t even get MARTA cards.

Sodexo has violently disrupted workers’ attempts to freely assemble and exercise free speech. In the past, Sodexo workers, many of whom are laid off each summer, faced the likelihood that unionization would lead to unemployment. In New Jersey, amidst widespread overcharging and undelivered rebates from Sodexo’s end, Tom McDermott of the Clarion Group, a food service consulting company, found that “In the [10] New Jersey districts, all competitive RFP [request for proposal] processes resulted in the incumbent retaining its contract, raising immediate questions about whether the bidding process is truly competitive.”

It appears that the “quality of life” Sodexo is concerned with servicing is that of its executives and shareholders at the expense of the basic human needs of its employees. At Emory, “quality of life services” means a meal plan that nets a large profit for the University while under-paying and under-providing for workers.

In 2013, Emory’s Committee on Class and Labor attempted an analysis on the quality of life for contracted workers on campus. The committee’s findings were startling:

“The committee was frustrated that we could not engage with contracted employees as we wished, and as we usefully did with Emory’s own employees. We could not gain independent information about important questions, such as whether some sets of contracted workers prefer part-time schedules, or whether employees find their company’s grievance procedures problematic. More generally, we could not ascertain how Emory’s contracted employees experience their situations on our campus. Notwithstanding the belief among Emory liaison officials that they have effective relations with these companies (exercising varying administrative styles), current arrangements limit the [U]niversity’s review of these companies’ labor relations largely to reviewing what the companies themselves report. The [U]niversity therefore cannot claim that it knows the status of the contracted workers’ experience.”

Emory’s mission statement is “to create, preserve, teach and apply knowledge in the service of humanity.” We cannot assure adherence to any of those values if the University has no means of knowing the workers’ experience. For the University to assert the presence of a safe and ethical working environment while simultaneously acknowledging in an official capacity that they absolutely cannot know the status of subcontracted workers is to promote an incoherent policy that resembles Orwellian doublespeak. Our mission statement itself calls for both the preservation and application of our knowledge to serve humanity. This hypocrisy cannot be tolerated.

Several of my peers and I who have written other editorials on this issue have been assured that there are plenty of informal interactions between Emory administrators and Dobbs Uuniversity Center (DUC) workers. But when the University’s own committee found that Emory “cannot claim that it knows the status of the contracted workers’ experience,” it seems reasonable to receive those assurances with skepticism. Absent a formal mechanism for enforcing standards on worker treatment, the University is relying on Sodexo to regulate and oversee itself.

In light of what we do know about Sodexo’s treatment of workers, it seems grossly irresponsible for the University to uphold their current regulatory approach.

We need actionable mechanisms for workers to complain directly to Emory, not just informal interactions, and we need a regulatory body with teeth, not vague commitments to generic liberal values.

To me the obvious question is this: if Sodexo and Emory are both so confident that they have done everything possible to uphold the stated values of a liberal arts university, why are they so reluctant to let a third party — or even an official Emory regulatory body — talk directly with workers? Why should we trust Sodexo to internally manage worker complaints when we know they have demonstrated a vested interest in suppressing everything from unionization to Emory committee officials speaking directly with workers? Sodexo’s track record speaks for itself — we cannot simply trust their word, and we can trust even less the idea that they will suddenly change their ways.

While we do need better oversight, the best thing that Emory could possibly do at this point is to say no to Sodexo when the food services contract is renewed in the coming weeks. It is clear to me that the presence of Sodexo on campus violates all principles and ethical commitments found in the University’s mission statement. If we claim to apply knowledge in the service of humanity, we must do better than Sodexo.

I have heard no compelling reasons to retain Sodexo. We must strongly resist the notion that contracting Sodexo could possibly align with our community values.

Andrew Jones is a College sophomore from Macon, Georgia.