On March 18, the market held its breath as Federal Reserve (Fed) Board of Governors Chair Janet Yellen delivered the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) March monetary policy statement.

As feared, the Fed removed the word “patient” from its outlook on normalizing interest rates. But in a deft sleight of hand, the Fed simultaneously indicated it would not raise rates over the next couple of months, indicating in fact, that it would remain patient.

Investors went wild, sending the S&P 500, a market index based on the performance of 500 large companies, soaring nearly 1.8 percent in the two hours following Yellen’s remarks. By market close two days later, the S&P 500 had finished the week above 2,100, snapping its three-week losing streak.

A few days later, a Clifton Road water main burst, cutting off water to the Emory Point apartment complex where I live. At the time, my hands were covered in teriyaki marinade. I went to the sink, used my elbow to hit the faucet ... nothing. For 12 more hours, I couldn’t wash my hands, use the bathroom or have a glass of water. When the water stops running, you lose all sense of normalcy, and life becomes completely dependent upon the Department of Watershed Management’s ability to dispatch emergency crews on a Saturday night. Experiences like this are a slap in the face that remind us how fortunate we are to live in the developed world and how completely inept we are when our normal expectations are disrupted.

The market has similarly become accustomed to the Fed’s easy money policy over the last six years. In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed started aggressively lowering interest rates to rescue the U.S. economy from its economic nosedive. Today, more than six years later and despite a recovered economy and a U.S. stock market at historic highs, the Fed has continued to hold interest rates at emergency levels. This “zero percent” rate policy has become a new normal — a new convenience — running water for the market, and the Fed has shown that it is unwilling to break the water main and disrupt normalcy. But unlike running water for human consumption, this new normal is bad policy.

The Fed’s March 18 sleight of hand shows a Fed pretending to move while steadfastly, and dangerously, standing still. Since 2013, the Fed has discussed tapering back its monetary intervention and eventually normalizing rates. But the Fed has continued to procrastinate, creating new defenses against normalization along the way. At first, the Fed cited lagging improvement in the labor market. Then, it was geopolitical risks. Later, it was currency headwinds and deflationary pressures. And most recently, the Fed has implied that it needs three months of perfect economic data in order to act. When has there ever been three months of perfect economic data?

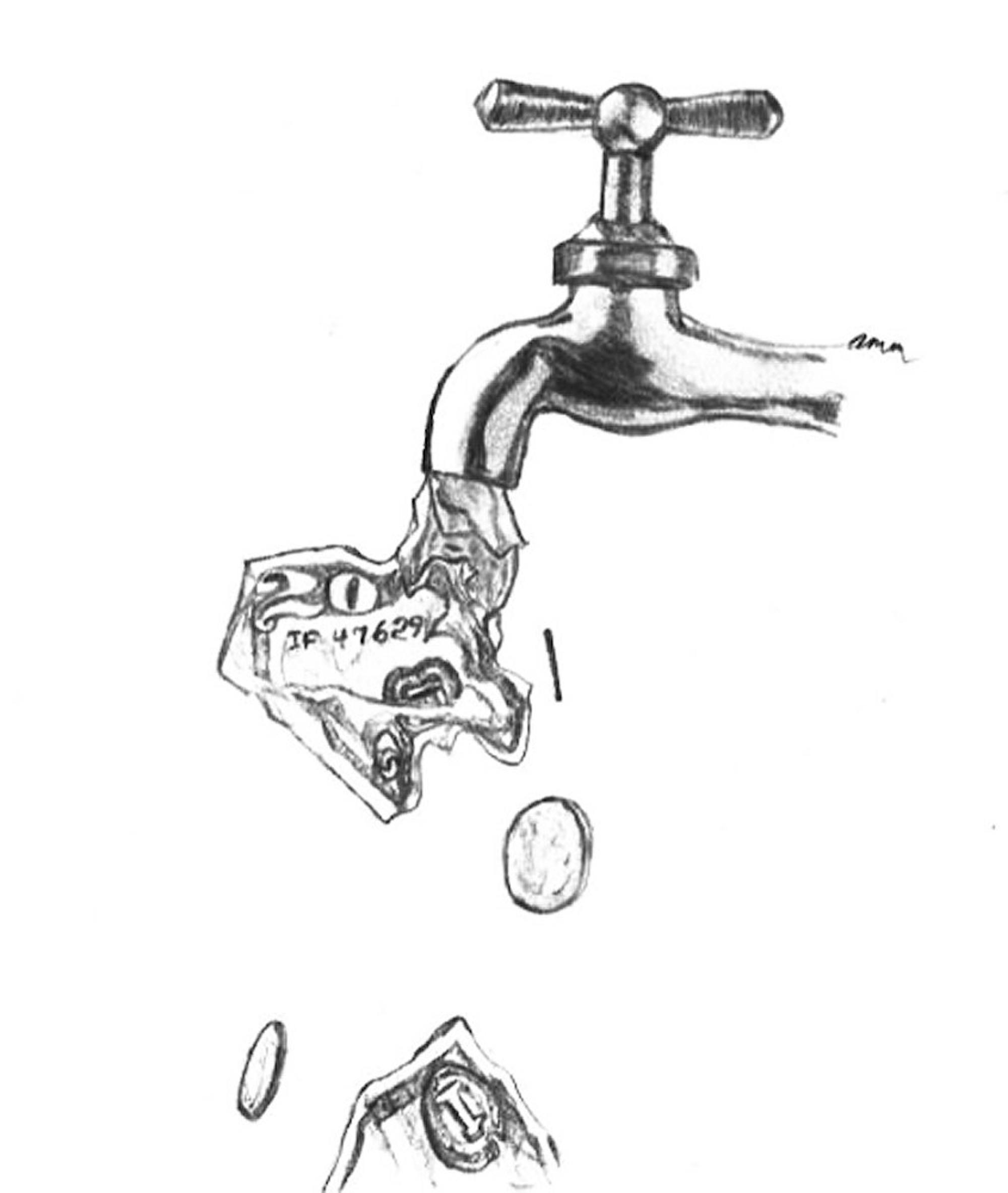

The March FOMC statement continues this trend. It shows no end in sight to the stream of easy money flowing from the Fed’s spigot. This continuous flow presents a significant danger to the market. The liquidity that the Fed pumped into the market to lower interest rates and jumpstart the economy in 2008 continues to flow into the market six years later. This flow forces asset prices up and can eventually create bubbles that jeopardize the entire financial system. In addition, with rates already at zero percent, the Fed would have little to no room to act in the case of a future economic downturn.

So, why does the Fed continue to stand still? Because like any of us, the Fed doesn’t want to disrupt normalcy, especially as the stock market trades at new highs, burying painful memories of the financial crisis. This comfort is the reason why the Fed won’t act meaningfully until it absolutely has to. Despite market anticipation that the Fed will act later this year, I am doubtful. But zero percent rates are not normal, and irrationality cannot last forever. Eventually the Fed will be forced to normalize rates, bringing reality back to the market. Let’s just hope that when the water stops running, the market will know what to do.

How Fed Policy Became Running Water, And Why the Market Needs a Permanent Water Main Break

Comic by Anna Mayrand