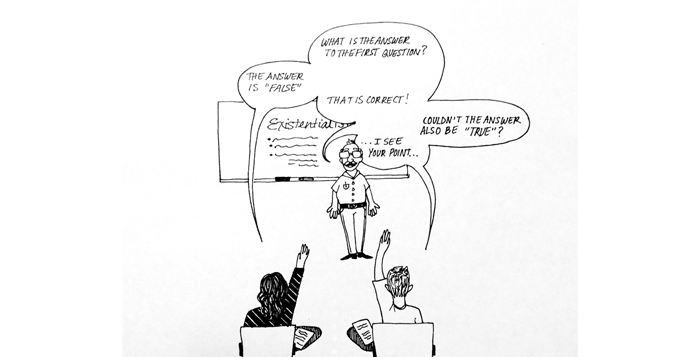

On Tuesday, my professor informed me that "there is no such thing as correct or incorrect." Fascinating. I asked myself if she could be correct in that assumption, then realized that the very question had become absurd and meaningless. The very act of questioning itself had lost its meaning. We were also just finishing a historical discussion that involved topics such as the Holocaust and ethnic hatred. Of course, the Holocaust wasn't incorrect -- or would that not be a correct statement?

This was the same professor who told us (perhaps "taught" is ironic here) that she didn't want to be teaching us anything. I think she meant this in the sense, that she didn't have a monopoly on knowledge. I know my professor meant well. Maybe she was attacking the binary approach to truth and falsity more than the conception of truth and falsity itself.

At the very least, I think, we should all acknowledge that truth is made of a slippery substance (if indeed it has substance at all) and no one should be making absolute truth claims (oh wait, was that an absolute truth claim?).

I don't have a problem with postmodernism or nihilism, but I do have a problem with the college classroom. In the humanities departments, at least, I'm seeing students pay hundreds of dollars an hour to sit through classes clicking through their newsfeeds, while professors calmly lecture on, as if their words have no significance – or worse, they sit and they nod and they smile while their students spout their feelings. What bothers me is that we are not being taught to think as much as to feel.

We learn early on to couch our observations with a set of hand phrases: "I feel like, maybe, ... [fill in the blank]." If a professor or student looks skeptical, we add a quick, "I don't know," or we throw in another "like." Thus any real substance to our thoughts, any rigorous rationality, sinks into a morass of subjectivity, relativism and emotion. Such a fear of being wrong doesn't really make any sense in an environment that claims no "correct" or "incorrect."

Part of the problem is that it is no longer socially acceptable to be an intellectual. We shun intellect like a disease, labeling it as "nerdy," "geeky" or plainly weird. It's just not cool any more. So we bury our feeble intellects in a hole of obfuscation, hoping that as long as people don't take the time to unearth the grave we've carefully left unmarked, then they will assume that something is going on in our heads and leave us be (provided you continue to pay tuition).

We continue, as Professor Mark Edmundson of the University of Virginia points out, to choose the "chill" professor, the one who gives the easy A. If a professor challenges and burdens his students, if he fails to entertain, he risks an empty classroom and losing his tenure. We don't speak of our courses in terms of what challenged us or made us grow so much as how much they entertained us: "I liked it. It was interesting."

Then there is the question of tolerance. We are oh-so-tolerant here at college. Every idea is valid. In our attempts to bolster the individual, we are terrified of touching things of personal importance. This happens especially with religion. We forget that for most, if they took their religion seriously, it forms the lens through which they see the world. Edmundson, therefore, is also right when he says that "religion is the right place to start a humanities course."

That is not to say that bashing one's religion for bashing's sake is appropriate, but considering religion's massive influence on our modes of thinking, religion can certainly play a more prominent role in academic discussion and dialogue. If college is going to be a place of debate, learning and rigorous thinking, I see no reason to abandon religion at the door.

But I forget myself. In a world without correct or incorrect, there really is nothing more to be hoped for. I can even end my sentences with prepositions (as I did that last one) if I so feel; the rules and strictures of grammar be damned! Why even read books, as if all of us here even do? We can just make up our own facts. It's infinitely more interesting, and a heck of a lot easier.

- By Jonathan Warkentine