As you enter the Michael C. Carlos Museum’s spring exhibit, dim lights cast protruding shadows across the mounted paintings, warping them into grotesque and ominous forms. “And I Must Scream” unapologetically highlights the monstrous, yet humanoid, figures that confront the inconceivable crises we face today.

“We’ve been thinking about monsters for almost as long as we’ve been alive,” said new student guide Ananya Mohan (24C). “It’s a question that we haven’t ever answered because we’re still asking it. You look at this artwork, and it turns out there’s as many answers as there are people.”

The exhibit features ten artists whose works are interconnected by five themes: corruption; human rights violations and displacement; environmental destruction; the pandemic and renewal.

“It’s great to have these plethora of concepts,” said continuing student guide Olivia Metzger (23C). “It’s very grounding to have tangible works of art that are beautiful and you can appreciate on an aesthetic level, but also it’s a gateway to really rich conversations.”

As you traverse through the gallery, these messy depictions of the natural and human worlds call for pensive reflection and an urgent plea for collective action.

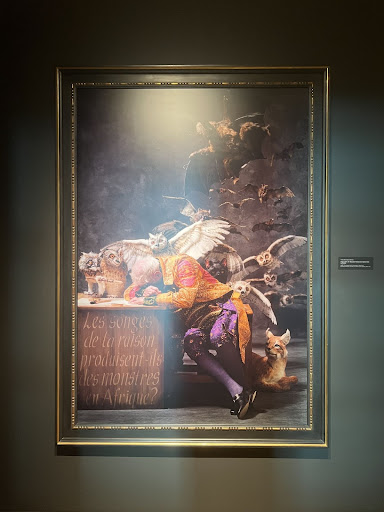

‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’

Right as you enter the space, you are faced with an eerily tall piece that features a man fast asleep on his desk as puppet-like owls and flying mammals envelop the background. Artist Yinka Shonibare grapples with the bridge between dreams and reality, inviting a conversation about the role of monsters in the human imagination.

“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” by Yinka Shonibare. (The Emory Wheel/Serena Ye)

“This exhibition especially describes our history of fear,” Mohan said. “It’s the things that people before us were scared of, but then we’re layering it with our own fears.”

The rich, vibrant hues of the batik fabric are eye-catching and symbolize lasting European colonialism. The dark red fabric, patterned with bold motifs of interweaving lines, has falsely become associated with African art. In reality, the fabric was created by a Dutch company emulating Indonesian batik clothing and has nothing to do with the continent. By exposing this stereotype through art, Shonibare calls into question the symbols that we associate with African culture and the interconnected effects of globalization.

‘Prophecy’

One of the most outstanding pieces of this exhibit is a series of six photographs created by film producer Fabrice Monteiro in collaboration with fashion designer Doulsy. In these stunning works, Monteiro depicts the horrifying destruction that humans wreck on the ecosystem through pollution. Wearing an oil slick dress made of garbage bags, a figure donning a scarf of seagull feathers and braids of shells emerges from the bay.

“Prophecy” series by Fabrice Monteiro. (The Emory Wheel/Serena Ye)

A warrior, wielding a turtle-shell shield, drags the webbing of fishermen’s nets as debris and animal caracasses cascade into the foreground. A solemn human heaves a burning torch of electronic cables amid an ashen field of discarded e-waste, ribbons from VHS tapes floating in the wind. Monteiro captures the ways in which capitalistic opportunism can pose irreversible havoc on our humanity. Through these monstrous and zombie-esque humanoids, the film producer and fashion designer combine their ingenious storytelling to depict the consequences of environmental damage caused by humans.

‘Malaïka Dotou Sankofa’

As you walk into the cave of the Taylor Room, a sense of isolation and solitude will wash over you. In a mixture of literary prose, photography and narration displayed through seven installations, artists Laeïla Adjovi and Loïc Hoquet tell the story of their character, Malaïka, in her journey from captivity to freedom.

“Malaïka Dotou Sankofa” series by Laeïla Adjovi and Loïc Hoquet. (The Emory Wheel/Serena Ye)

Malaïka is trapped in a dark cellar with no chance of escape, crowded by the overbearing boredom of assignments. Dressed in a bland, Western-styled suit, Malaïka’s beautiful wings are cramped and unstretched. Her wings are a pretty patchwork of historical and contemporary styles; these lively cerulean blues, bloody reds and lemon yellows seem to have no place in the dingy cellar. The artists draw the creature’s wings as a metaphor for the weighing impact that African colonialism has on the continent and as a cry for pan-Africanism. Malaïka is determined to escape, and by crumbling the walls with the power of her wings, she tastes her first lick of individualism. In the final piece, she stands confidently like a bird with its neck craned back, looking back at the past to move forward.

‘The Buddhist Bug’

Wandering deep into the exhibition, you’ll come across a ginormous spiraling coral chute. Reminiscent of those IKEA tunnels or a playground slide, “The Buddhist Bug” tracks a new horizon of spiritual and social interpretation among everyday life.

“The Buddhist Bug” by Anida Yoeu Ali. (The Emory Wheel/Serena Ye)

Cambodian artist Anida Yoeu Ali wore this 100-foot-long installation, with her head popping out of the top as well as another performer’s legs popping out of the bottom, during her trek through Cambodia. Ali ventured across classrooms, marketplaces and food stalls to gauge how people would react to this whimsical piece. The artist took inspiration from the orange-colored robes of Buddhist monks as well as the Muslim hijab to portray her emotional turmoil between Buddhism and Islam. She explores how religion can extend to the body and exaggerate our interactions with people. Through its abstract absurdity and alien form, Ali aims to initiate conversations on multireligious countries, highlighting their overlaps and differences.

As you exit, you’re left with a bone-chilling reflection of the integrated crises that humanity faces today.

“Renewal — you’re supposed to feel fear and horror and pity, but at the end of it, they don’t just leave you in that headspace,” Mohan said. “It’s very clearly laid out what we need to do as a collective; it’s a warning, but a warning means that it’s not too late.”

Monsters appear in all shapes and sizes, but one woven similarity is monsters’ ability to consume until nothing is left. Before we know it, our lungs will turn into leaden, chemical-heavy stones, our skin will burn from the toxins flooding through the ocean and our faces will numb toward the carbon dioxide expanse and cluttered deserts of permanent garbage.

“Monsters are symptoms of structural issues,” Metzger said. “You can’t point it back to one individual — it’s all of us polluting, consuming and being complacent.”

As humans, we are innately selfish and self-centered. Yet, we have the agency to make decisions for ourselves. Should we utilize these monsters for further destruction, or should we reframe these monsters as vehicles for collective compassion? The choice is up to us.