“Breaking Bad” is a great show by almost all accounts. The AMC hit TV show, which started in 2008 and will be coming to an end this fall, has won several Primetime Emmys and is highly acclaimed both critically and popularly.

I will admit that I’m very late to the party, having started watching the show only a couple days ago. That said, I’m almost done with the second season, and by the time of publication, I undoubtedly will have conquered the third season as well.

Few TV shows have the ability to be as addicting as their subject matter, but I imagine that “Breaking Bad” comes pretty close to methamphetamine itself. Multiple factors contribute to its success. Not only is it about the production and distribution of one of the most dangerous drugs in the world, but it’s also a well-produced show. The direction is commendable, the writing and plot structure are engaging and the actors are consistently convincing.

Furthermore, the characters are complex and multidimensional. The main character, Walter, is a troubled, enigmatic and highly-overqualified chemistry teacher, and similar depth is evident in his wife, Skylar, brother-in-law Hank and partner-in-crime Jesse.

However, I do have a big problem with the main character’s teenaged son, Walter Jr. In stark contrast to every other major character on “Breaking Bad,” Walter Jr. is one-dimensional, shallow and predictable. He is a stereotypical teenager: rude, obnoxious and aloof. At least by the end of Season Two, Walter Jr. has yet to have any significant redeeming qualities.

For me this is problematic, as Walter Jr. is the only representative of young people in the show. Granted, I am only informed by a total of 20 episodes at this point, but the principal is the same.

If a black character were similarly unsympathetic for two entire seasons against a backdrop of strong, well-rounded white characters, the show would be heavily criticized. (As it stands, the only black character in the show is an oncologist who is responsible for treating Walter’s lung cancer.)

You may be asking, “What’s the big deal? I think Walter Jr. is a pretty accurate character. Teenagers are typically rude and obnoxious.” Of course, the big deal with these stereotypes is the same big deal as with all stereotypes: they are not true, and they give an unfairly negative image of the subject.

Young people occupy a unique position in society. Short of getting a sex-change operation or bleaching your skin, age is the only fluid demographic. As such, it may not seem important to identify instances in which young people are generalized and stereotyped. After all, we were all young once, so we all know what it was like.

But this thinking only legitimizes and encourages the continued marginalization of a significant portion of the population which has virtually no political representation or economic power – young people cannot vote and disproportionately live in low-income families.

For the writers of “Breaking Bad” to create a character as unsympathetic as Walter Jr. based on the fact that he is young is not only lazy on their part, it is also insulting.

Discrimination and stereotyping based on age is just as damaging to society as discrimination and stereotyping based on race, gender, sexual orientation or any other identity. Walter Jr. behaves exactly as you would expect a 15- or 16-year-old teenager to behave, and therein lies the problem. What if he behaved exactly as you would “expect” an African-American person or a gay person to behave?

Granted I am not even halfway through the series yet, but ageism is as legitimate of a problem as racism or sexism. Even one or two instances of racism in a show as popular as “Breaking Bad” would undoubtedly cause public uproar. Why should a distinct pattern of ageism be any more acceptable?

William Hupp is a College junior from Little Rock, Ark.

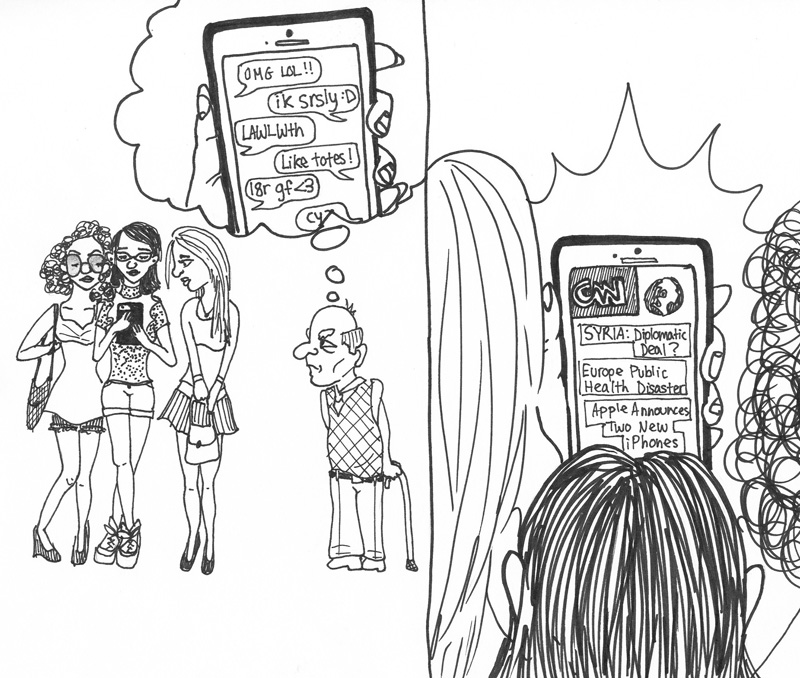

Cartoon by Priyanka Pai

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.

Interesting article, William. You raise a good question about art and character development. I am in a writers group which is mostly white, with some African-Americans and people from other continents. We have had interesting discussions when someone is presenting a work and one of the members objects because we think a character is is depicted in a way that is racist, or any other “ist.” Is it the job of an individual artist to fight for social change? If most of the shows available depict teens badly, and it makes you mad, you have a movement to lead and you will win, because you are the target demographic of all media in the universe. Advertisers do not want to offend you; they want to be your friend.

Ageism is wrong in both directions. BTW, the cartoon next to your article is very funny. Is it your work? I like it. Made me laugh. A lot. But someone might think that the older male figure is also ageist, depicting an older man who is grumpy, hates kids and does not get technology. Do some of those people exist? Yes. But it is a stereotype that probably annoys people of your parents’ or grandparents’ generations, particularly those looking for a job who cannot get an interview because of those stereotypes.

It’s not that Walt Jr.’s character is shallow because he’s young. He’s shallow because he’s a moron.