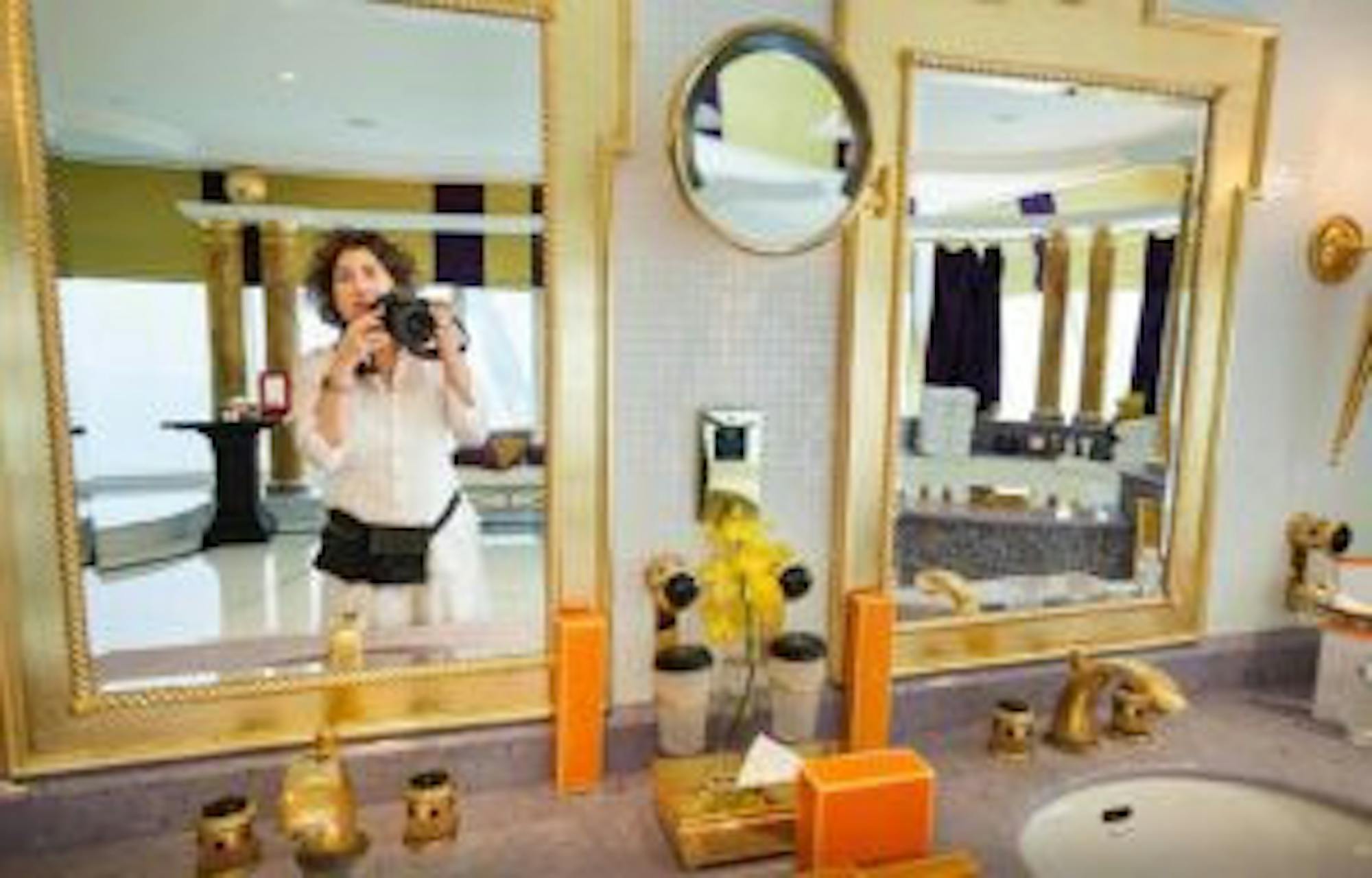

Courtesy of Lauren Greenfield and Magnolia Pictures

At a time when the one percent owns an alarmingly disproportionate amount of wealth, images of upper-class grandeur saturate our culture and portray excess as something to aspire to, symbols of the all-too-abstract notion of “making it.” In her new documentary “Generation Wealth,” artist Lauren Greenfield, a veteran of the upper-echelon of contemporary society, cuts open this malignant malaise with a scalpel, revealing how deeply it has invaded our everyday lives.

Greenfield has tackled modern wealth as her signature subject for two decades, whether in the form of photography, anthropological research or documentary filmmaking. In “Generation Wealth,” Greenfield reflects on her portfolio by compiling a retrospective exhibit of her staggering array of visual documents, which chronicle the parties, possessions and people at the top of the social ladder. During this process of reflection, she speaks with people she photographed, including bankers, high schoolers, porn stars and debutants. One of the most fascinating is Florian Homm, a German banker who was recently released from jail at the time of filming. Through these personal visits and pieces from her own oeuvre, Greenfield turns her camera back onto herself and modern society at large, diagnosing the ills of our obsessions with money, fame and work, revealing how they all contribute to late capitalism’s decline.

When a documentary filmmaker becomes a character in their own work, it almost always raises eyebrows. It can be uncomfortable, as we are often led to believe that documentaries should be objective, even though the implicit bias of authorship prevents these works from ever achieving such a standard. Filmmaker Kirsten Johnson included herself thoughtfully in her 2016 film “Cameraperson,” which pulled from her decades of footage to construct a compelling essay about ethics and biography. “Generation Wealth” channels a similar wavelength, though to a weaker effect. Greenfield doesn’t successfully take the dive into knotty threads of ethical questioning, but she does effectively analyze her relationship to her subjects. She achieves this through bringing her subjects into the filmmaking process. Ethically, this is her most successful move, and it’s what prevents “Generation Wealth” from becoming a full-on vanity project, though it naturally borders on it. Centering the film on her own career, in retrospect, proves risky for Greenfield, but mostly works as a springboard for her broader concerns.

Both formally and narratively, Greenfield’s exploration of her own work makes a strong backbone for what could have easily been a much messier film. “Generation Wealth” is a collage with a clear through line, from a history of the modern bourgeoisie to a deeply personal reflection on family. Greenfield and her four editors — Victor Livingston, Dan Marks, Aaron Wickenden and Michelle Witten — adeptly combine existing footage, still photographs and other audiovisual forms into something relatively coherent. However, the interviews and home movies pack the biggest punch, creating a beautiful parallel to the stunning portraiture found in Greenfield’s photography. As a whole, though, “Generation Wealth” lacks a conclusion. Starting about halfway through its 106-minute runtime, Greenfield’s arguments become scattered and she feverishly ties up loose ends along the way. She simply loses focus at this point, and as a result, her final passages lose narrative momentum.

At this point in the film, Greenfield clearly implicates herself with workaholic culture and its poisonous effect on the family, refusing to show any clear reconciliation for herself or her interviewees. It’s the closest thing to an ending that we get with “Generation Wealth,” and, even though it is an easy emotional nerve to touch, it’s undeniably powerful. Connecting the corrosive allure of wealth and personal achievement to the disintegration of social relationships is the strongest of many points that she makes throughout the film. It’s easily illustrated by the people she interviews, including a banker who struggles to have a child and a woman so obsessed with plastic surgery that loses hers. Lastly, the power of this argument sits within Greenfield’s own self-examination. She turns the camera on her children, along with her own uneasy relationship with her mother. Standing in for broader suffering, the victim is the parent-child relationship.

In the end, Greenfield makes a point of cycling her work back into the community. When her retrospective exhibit opens, the people she photographed are invited. Perhaps this was her ultimate goal, to create a dialogue and encourage others to examine themselves just as she has, particularly on how they all engage with our current culture of wealth. And here is where most of “Generation Wealth” roughly converges — in a gallery where everyone is a small part of a bigger portrait. Many of the film’s participants show up, seeing themselves reflected in a picture frame. The film belongs to all of them, and it belongs to us as well.