On Oct. 11, an Oxford College sophomore was arrested for threatening to carry out a mass shooting on campus on the social media platform Yik Yak. A day after the threat the Oxford Student Government Association (SGA) voiced their concerns to Emory officials that Emory had left the community without information for almost 20 hours. On Oct. 13, Emory replied to the SGA with the University’s official protocol and the steps the University took in response to this incident.

“As you are very aware, the recent situation regarding a gun threat on campus has left many students and families of these students frightened, upset, or concerned, mainly due to a lack of communication between the student body and the police force/administration,” Oxford SGA Public Relations Chair and sophomore Konya Badsa wrote in her email to Nancy Seideman, associate vice president for media relations; Samuel Shartar, head of CEPAR; and Craig Watson, chief of Emory Police Department (EPD).

Emory’s response to Oxford SGA’s email stated, “We’ve concluded that a more timely campus communication following the student’s arrest would have benefited the community.”

The Timeline

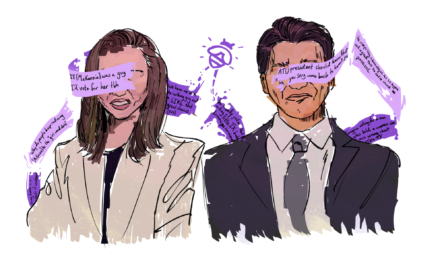

On Oct. 11 around 12:30 a.m., Oxford College sophomore Emily Sakamoto wrote on Yik Yak, “I’m shooting up the school. Tomorrow. Stay in your rooms. The ones on the quad are the ones who will go first.”

Neither Sakamoto nor her family could be reached for comment.

EPD sent extra officers to patrol the Oxford campus, according to Emory’s response to Oxford SGA’s email — which Oxford SGA sent to the Wheel.

“Most students found out about this threat either through Facebook, text messages or Yik Yak, rather than an official source or channel of communication, which heightened panic,” Badsa’s email stated.

That afternoon, EPD traced the threat to Sakamoto, issued a search warrant and arrested Sakamoto at 4:30 p.m., after she confessed to the charge of terroristic threats.

Emory’s response to the SGA email said that the team judged that it was “appropriate to hold communications” until the situation was resolved. It said that the post was not an imminent threat to life.

A few hours later, the University attempted to send an all-Oxford email, but a “technical glitch” held the message back from students, while faculty and staff received the email, according to the University’s response.

Not only did the statement say that the University concluded that more timely communication would have been beneficial, it added that they are exploring the technical issue.

Around 8:30 p.m., Stephen Bowen, dean and CEO of Oxford College, successfully sent an email to all Oxford students briefing them on the threat.

“During [the time between the threat and Bowen’s email], students had no idea if it was OK for them to leave their rooms, go get food, use the bathroom,” Oxford sophomore Emmaleigh Calhoun said. “No one knew what was happening.”

Sakamoto was released from jail on Oct. 12 on a $1,500 bond. According to Bowen, she has been placed on interim suspension by the University.

The maximum penalty for terroristic threats is five years in prison and a fine of $1,000, according to Layla Zon, the district attorney for Newton County, where Oxford is located.

“Generally, when the District Attorney’s office is taking a position on bond, we consider whether the individual poses a risk of committing additional crimes if allowed on bond,” she wrote in an email to the Wheel.

Emory administration sent an email to all Emory students on Oct. 16 that covered safety precautions and available mental health services at Emory. The email did not reference Sakamoto’s threat.

The Protocol

In the response, Emory stated that the University immediately engages official protocol after a 911 call. In this case, the response team included EPD, CEPAR and members of Oxford’s emergency preparedness team, the response stated. Sometimes, Emory will ask for additional assistance from other law enforcement agencies.

If the team identifies an “imminent threat to life or health,” they send an emergency notification to the Emory community, according to Emory’s response. Otherwise, they inform the community through an e-mail or web posting.

“If there is an imminent threat to life, then Emory’s emergency notification system is activated through a RAVE alert (text message), along with sirens, emails and web postings,” according to the response. “In these cases, a judgment must be made regarding the most responsible and effective approach to communicate with the campus community, in a way that balances the dissemination of actionable information with the risk of initiating unnecessary panic among students, their parents and the greater community.”

The University’s response to Oxford SGA’s email encouraged the community to “appreciate” the various factors that go into making communication decisions.

In Retrospect

“I don’t think it’s the actual threat that we’re upset about. It’s honestly the lack of communication between the University and the students,” Oxford sophomore Yasmeen Wermers said. “This could have been a legitimate shoot out.”

Wermers was off campus when she heard about the threat through her friends and decided not to come back to campus until she received an email from administration. She said she and her peers continuously checked Emory Alert but had to resort to word-of-mouth.

“There is still some fear that lingers around campus only because we don’t know how we’re going to be informed or if we’re going to be safe,” Wermers said.

Bowen said not all students have shown concern.

“I had dinner with a group of students on Wednesday following the Sunday event,” he wrote in an email to the Wheel. “They had learned the specifics of the way the threat had been handled and were largely unconcerned.”

In a letter to the Oxford community, Cristian Zaragoza, Oxford sophomore and SGA chair of the Public Safety Committee, said he is more confident about how Emory handled the incident after receiving the response to the SGA email. However, he still questions the delayed notification and suggests even a simple Twitter update to alleviate panicking students.

“Because Oxford is such a tight-knit community,” he wrote. “It makes more sense to have everyone on the same page and aware of what is going on, rather than to have some people hiding out in their rooms and others going about their day because they are completely unaware of any potential threat.”

Managing Editor Zak Hudak and Executive Digital Editor Stephen Fowler contributed reporting.

Correction (10/21 at 4:32 p.m.): In paragraph fifteen, the article stated that Emory’s Oxford campus was located in Walton County. It is actually located in Newton County.

emily.sullivan@emory.edu | Emily Sullivan (18C) is from Blue Bell, Pa., majoring in international studies and minoring in ethics. She served most recently as news editor. Last summer, she interned with Atlanta Magazine. Emily dances whenever she can and is interested in the relationship between journalism and human rights issues.

Oxford is located in Newton County, btw.