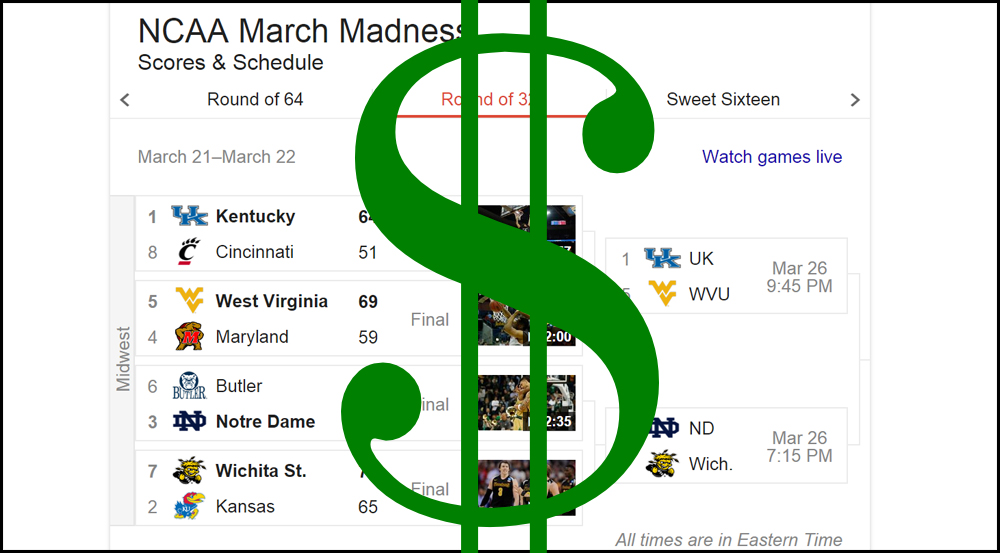

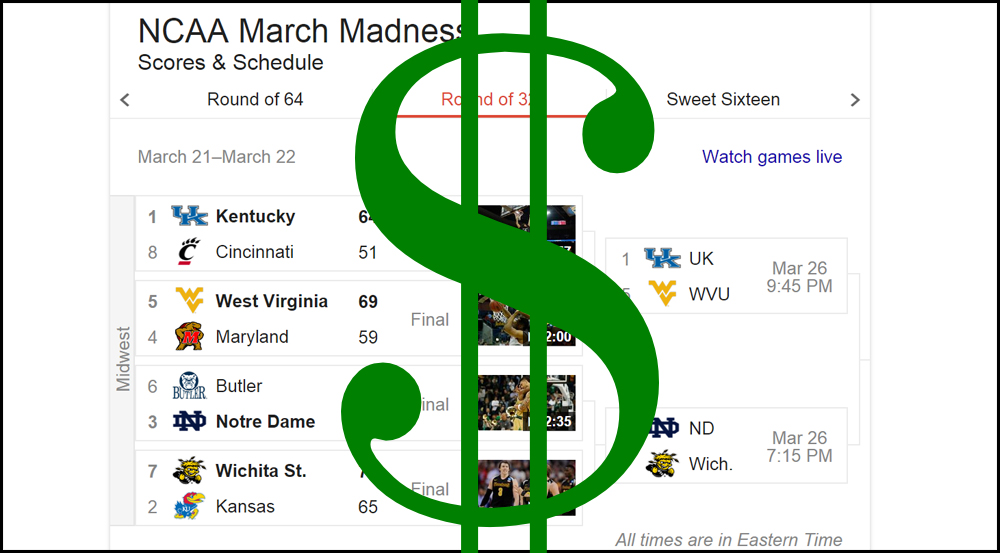

Not to be confused with the breeding season of the European hare, “March Madness” is an apt name for the nationwide obsession with the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Men’s Division I championships. Mostly because it A) occurs in March, and it B) drives people who would never engage in risky fiscal decisions to bet exorbitant amounts of money on college kids.

This year, March Madness started on March 17 and will conclude with the championship game on April 6 in the Lucas Oil Stadium (fun fact: aside from the bizarre implications of an automotive oil company holding naming rights for a sporting venue, the Lucas Oil Stadium had a construction cost of $720 million).

In a recent “main story” spot on Last Week Tonight, host and comedian John Oliver spent more than 20 minutes lambasting the exploitive and money-laundering machine that is the NCAA.

In it, he explains that the NCAA accrues more than $1 billion in ad revenue from just the tournament, college coaches have salaries in the millions not including other avenues of income (radio shows, TV spots, etc.), and meanwhile, college athletes are paid nothing.

Putting aside the atrocities committed by the NCAA (and other sports leagues that claim to be nonprofit – I’m looking at you, NFL) and not to mention the joke of an education that some athletes receive, there are other problems with the March Madness money conglomerate.

An estimated $12 billion was spent worldwide on March Madness gambling last year. There are several countries on this planet whose gross domestic products (GDPs) – an aggregate measure for total national output – don’t exceed that number.

At the risk of sounding incredibly condescending, I want to take this opportunity to explain why it is so astounding that people spend money betting on March Madness (or any large-scale sporting event for that matter).

An estimated 100 million people in the Unites States – a third of its population – are expected to participate in tournament-style bracket contests. The likelihood that a person will predict a perfect bracket out of the 9.2 quintillion bracket combinations is infinitesimal. You might as well bet on which individual sperm cell will be the one to fertilize the egg of your future offspring.

Let’s not forget the fact that, while a third of the population is collectively spending money that many people don’t even make over the course of a lifetime, the practice of gambling on sporting events is only legal in four, yes four, states: Oregon, Montana, Delaware and Nevada. Furthermore, the idea that thousands of random businesses are capitalizing on (and exploiting) your genuine love for a sport should grind your gears to a point where your desire to gamble on college basketball dissolves as a result of anger.

Alright, so say statistics, legality, and capitalistic greed just don’t do it for you.

Say you find it beyond thrilling to lose money every year around springtime (because, let’s be honest, you inevitably screw up your sweet sixteen).

If that’s the case, then my last ditch effort at convincing you to stop wasting your money on March Madness gambling is much simpler.

You are betting good money on the assumption that 500 college students will perform consistently and reliably to not only the best of their ability but also in a way that matches their previous performance.

I once heard a story about a Division I college football player the night before a noon kickoff in a college bowl passed out drunk at around 5 a.m. That’s not to say that college athletes are by any means irresponsible.

All I’m saying is, I am a college student. I know how we are. And I’m sure you do too. All of this is to say that the next time you get out your checkbook, perhaps consider funneling your funds to a slightly more meaningful (or at the very least personally profitable) endeavor.

But, if I were a betting (wo)man, there’s no way in hell I would bet on March Madness.

There’s almost definitely more money in betting on American elections.

If only there was some way the NCAA could team up with the Koch brothers to form a fantasy sports-cum-politics league. Then we’d really have something to get “mad” about.

[quote_box_avatar name=”Rupsha Basu” position=”Executive Editor” avatar_img_url=”http://i.imgur.com/BVxKrLb.jpg”]The likelihood that a person will predict a perfect bracket … is infinitesimal [/quote_box_avatar]

Rupsha Basu (16C) was the Emory Wheel's executive editor from 2015-2016 and served as the Wheel's news editor prior to that. She currently attends New York University School of Law.

Perhaps you could describe these so called “atrocities” the NCAA commits?? I’m no fan of the NCAA either, mind you, but that’s a little much. And the NFL certainly makes no claims as a non-profit. Finally, obviously no one believes that their bracket will be perfect. But bets people actually make for fun and profit (such as Kentucky winning the championship) are indeed far greater than your disgusting analogy. But nevertheless damn you capitalism for adding interest to the most exciting sporting event of the year!!! Give me a break.