How do the struggles of the undocumented hearken back to the Civil Rights Movement?

A panel explored that question as part of Emory’s week-long celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr. on Thursday night.

The King Week discussion titled “Dreamers: Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow,” drew on the discrimination and violence African Americans faced during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, as well as those faced by the children of immigrants who have come to the U.S. without proper documentation.

The two students and a professor from a school dedicated to immigrant students’ rights joined Emory Associate Professor of African American Studies Carol Anderson for the event at the Woodruff Health Sciences Center Administration Building (WHSCAB). Chief Executive Officer of the National Center for Civil and Human Rights (NCCHR) Doug Shipman (’95C) moderated the talk.

Laura Emiko Soltis (’12G), the executive director of Georgia’s Freedom University - a school that provides college-level courses and scholarship help to undocumented students unable to apply to many public schools in Georgia, presented to the audience her own photographic work, some of which depicted Georgia police arresting Freedom University student protesters.

The two Freedom University student panelists, Arizbeth Sanchez and Ashley Rivas-Triang, had both participated in numerous such protests and had been arrested numerous times.

“The charge was criminal trespassing,” Sanchez, 20, said of her arrest after a Freedom University-organized lecture in a building that closed before the talk had finished.

Emiko Soltis described the struggle endured by undocumented students under the Georgia University System Policy 4.1.6, which prevents undocumented students from enrolling at any of the Georgia System schools. In juxtaposition, Anderson, the Emory professor, described the era of school segregation in the American South.

“You had kids fighting through that sort of Jim Crow education system, saying, ‘I’m going to college,’” Anderson said. She then told the audience of an African American man who graduated from college, applied to the public law school in his state - where he paid state taxes - and was denied for his race.

“You shouldn’t have to leave home,” Anderson said, referencing the right of taxpayers to in-state tuition. “If you’ve got the bona fides, you’re in.”

Soltis emphasized the parallels to a current economic hurdle: the Georgia University System’s Policy 4.3.4, which denies in-state tuition to undocumented students.

Sanchez and Rivas-Triang recalled their sense of defeat when they realized that their state’s public schools were not available to them.

“Imagine you’re a junior in high school, you want to go to this college and you’re really excited and want to apply early decision, and you find that everything you’ve done for the past 11 years has been for nothing,” Rivas-Triang said. “I felt pretty useless — well, I have a high school diploma, so, now what?”

Sanchez added that common rhetoric used to describe undocumented immigrants often cuts deep.

“The words start getting to you — ‘they’re animals,’ ‘they broke the law,’” she said. “Immigrant rights are human rights, and as a human I feel inferior.”

Anderson echoed something similar when asked by moderator Shipman what the best strategy for pushing forward a social movement.

“What nonviolence [under King’s leadership] did was show the core of morality of human beings,” she said. “When you’re in your Sunday best and you have fire hoses pummeling you down the street, that image is a shock to the conscience.”

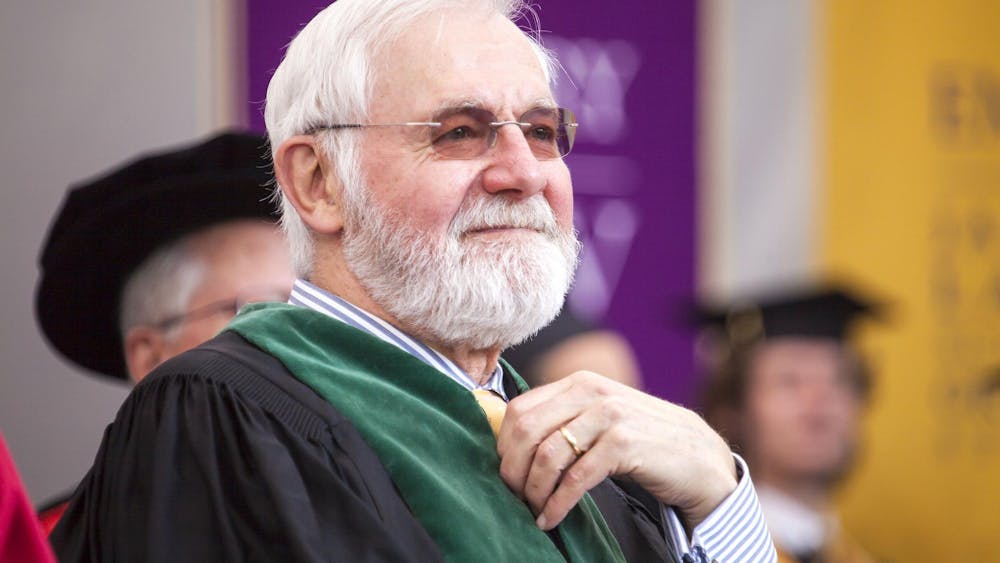

Later, Anderson handed the microphone to Shipman and raised her hands in a symbol of the protests against the shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black man, by a white officer in Ferguson, Missouri last summer.

“To put your hands up in the sign of ultimate submission, and to be seen as the ultimate sign of defiance - that is powerful,” she said.

Emiko Soltis revealed more photographs of Latino students holding signs that read “Brown is Beautiful,” “We Are Human” and “Lift the Ban,” as well as images of undocumented students partaking in a busy street sit-in, some as young as 16, prior to their arrests.

“I think being visible, showing your humanity” is the best way to propel a social movement,” said Emiko Soltis, who agreed with Anderson’s emphasis on nonviolence and visibility in the media as means of success.

Sanchez and Rivas-Triang, both of whom have applied to several colleges in the United States last fall, agreed that students who are citizens of the United States could have a positive impact on the undocumented students’ rights movement by pressuring their school administrations to make changes and by spreading awareness.

“A lot of people don’t even know about the [Georgia University System] ban,” Sanchez said.

Emory allows undocumented students to apply, but does not offer them merit- or need-based aid, according to Andy Kim, a College senior, Volunteer Emory staff member and co-founder of the undocumented students’s rights group Freedom at Emory.

“They could get an acceptance letter, but then find out that they can’t afford it,” Kim said. “It would almost be better if they just got rejected from the get-go.”

He added that Emory, a private university with a large endowment, has “a unique opportunity” to give undocumented students the ability to attend college in-state.

Rebecca Du, a College senior and the executive director of Volunteer Emory, said the desire to hold a panel on undocumented students and civil rights arose after Congressman John Lewis brought the similarities of the issues to light at his commencement speech last spring.

“He said it was our turn to stand up and get in the way, and he specifically mentioned the way undocumented students’ issues paralleled with the civil rights movement,” Du said, adding that Volunteer Emory saw King Week as the perfect opportunity to host an event on the topics.

“This was such an amazing combination of people - the student panelists were so brave and admirable,” she said. “Having undocumented students here our own age really brought home the connections we have to them as students ourselves.”

- By Lydia O’Neal, Asst. News Editor

Panel Compares Civil Rights Era, Today’s Immigration Policies

Emory professor of African American Studies Carol Anderson raised her hands in reference to the protests against violence against black people in Ferguson, Missouri at a panel to discuss parallels between the civil rights and undocumented students rights movements. Photo by Thomas Han / Photo Editor