Right before I left for college, John Mayer wrote me a letter on a plane. The story is less interesting than it sounds, but it’s still one of my favorites to tell. It is my go to “fun fact” when I’m forced to play an icebreaker game, one that either elicits dropped jaws or reinforces people’s preconception of who I am because, yes, I am from Los Angeles and no, seeing Gwen Stefani at the frozen yogurt shop down the road from my childhood home every so often is not a big deal.

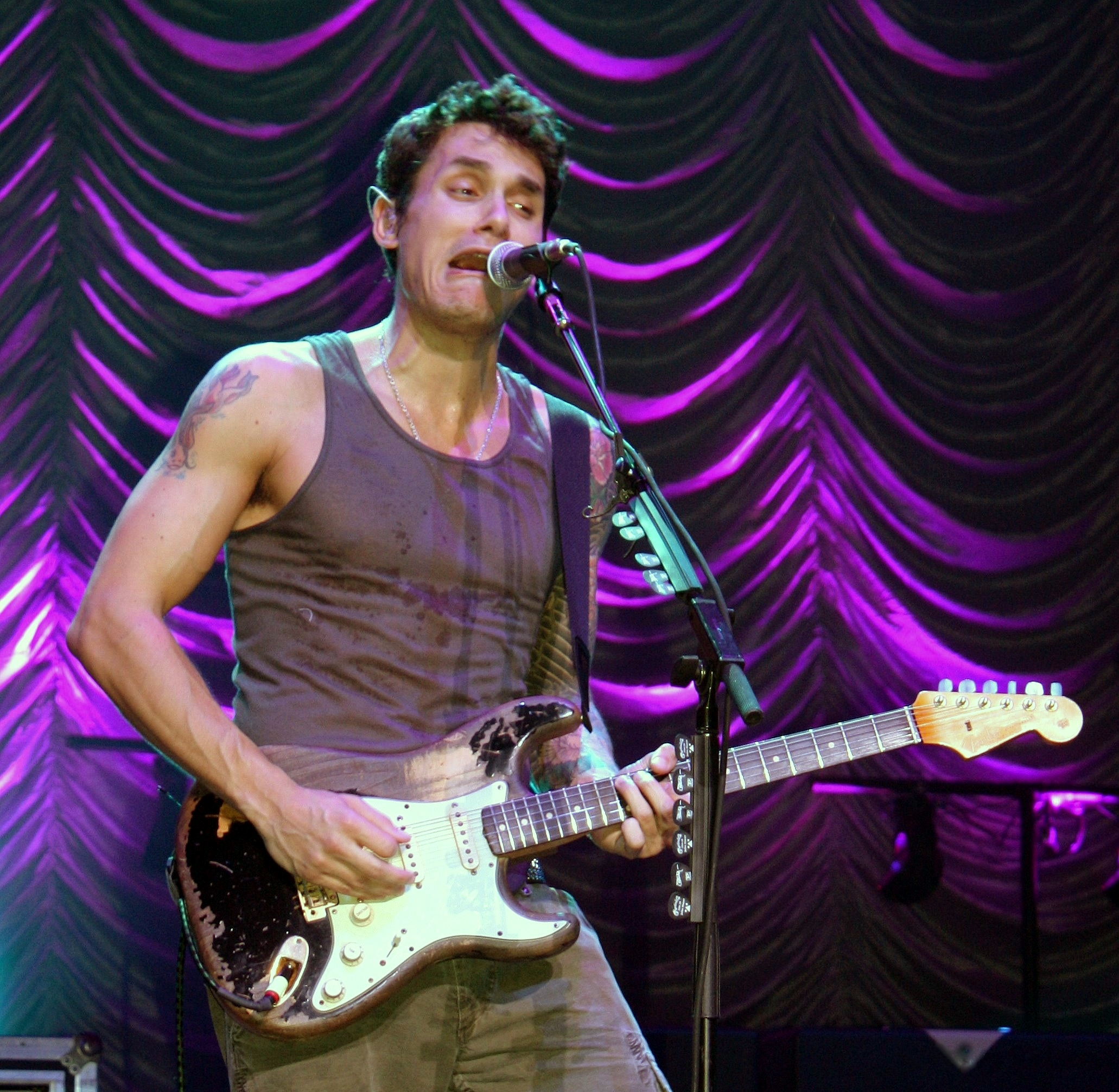

He was sitting in seat 7A on an American Airlines flight from Charlotte to Los Angeles, wearing a suit and black aviators. I was in seat 14F, wearing an Emory t-shirt and leggings. I spent the first two hours in the air writing him a letter about leaving for college, riddled with questions about nostalgia and confusion around growing up, thanking him for being the only artist that my family of six can always agree to listen to during long car rides.

I gave the letter to the flight attendant. She gave it to him. Not for one passing moment did I think that he would ever write back, but he did, and I walked off the plane, my hand holding onto to the thin, ivory Moleskine paper covered in his signature all-caps handwriting. A month later I watched him headline Music Midtown.

I suppose the crux of this story resides in the fact that he was traveling to Los Angeles to start writing his new album. He tweeted the next day that he was “back to the blues,” returning to work on creating the sound that defines his most critically acclaimed album, Continuum (2004).

Two-and-a-half years after we both walked off the plane at LAX, Mayer’s 10th album — The Search for Everything (2017) — has been released. Kind of. Mayer has so much content that he is releasing the album in waves. Each wave consists of a four-song installment released every month of this year, an unconventional production choice making his music more accessible to listeners.

“If you don’t like these, don’t get the next four. But if I’ve engendered some kind of trust that you think I’m onto something, get the next four, and come along with me on every single wave,” Mayer said, in an interview with Rolling Stone.

The album’s first single, “Love on the Weekend,” establishes a light, summery feel, evocative of the songs that made Mayer famous when he released his first debut album, Room for Squares (2001). “Love on the Weekend” can be characterized as a pop song, good for easy-listening on a Sunday afternoon. Though I believe this song falls short, the wave as as whole is by no means a regression for Mayer. “I am not done changing/Out on the run, changing/I may be old and I may be young/But I am not done changing,” Mayer sings in “Changing,” which serves as the incorporeal thesis statement for the album as a whole, one about searching and moving onwards. The song is simple in its acoustic sound, layered with his raspy vocals, but is ultimately too rudimentary to have a strong effect on its listener.

In “Moving on and Getting Over,” which is riddled with falsetto and electric guitar riffs, Mayer reaches a state of letting go. In “You’re Gonna Live Forever in Me,” Mayer sings “Life is full of sweet mistakes/And love’s an honest one to make.” The lyrics are tender, begging and ultimately achieving the listener’s compassion for the long-lasting effects of love. It is the strongest in this release, exposing the audience to a vulnerable side of Mayer not usually associated with his music.

Since he first entered the public eye, Mayer’s reputation has been complex and multifaceted. In the past, he established himself as a celebrity womanizer, an ego-maniac who self-barred interviews for a while and maintained a sporadic social media presence. Mayer seems to have turned a new leaf, focusing on his fans and his music as well as honing in on his talent (Eric Clapton deemed him a “master guitarist”). In this album, Mayer asks the big questions and explores what it means to adapt and move on, to fall in love and then “get over” someone, and to have an enduring presence in someone’s life.

In his letter, Mayer told me to “get anxious,” to “get calm,” to “dance” and “to know it is all for a good cause.”

“I’m 36, and I’m still searching,” Mayer signed at the end of the letter, reminding me that though I was about to move away from home and embark on a new journey, it was better that I didn’t have all the answers.

At 40, it is doubtful that Mayer has reached the end of his search, but perhaps for him, riding each of life’s waves one at a time is the only way to not drown in its complexity.

The first installment from The Search for Everything is available on iTunes and Spotify.

hannah.conway@emory.edu | Hannah Conway (18C) from Los Angeles, majoring in American studies with a concentration in life-writing, narrative and memory studies and minoring in media studies. After serving as music critic for the arts & entertainment section, she became arts & entertainment editor before studying abroad in Copenhagen Fall 2016. In addition to the Wheel, Hannah is a sister of Gamma Phi Beta and a frequent concert-goer.