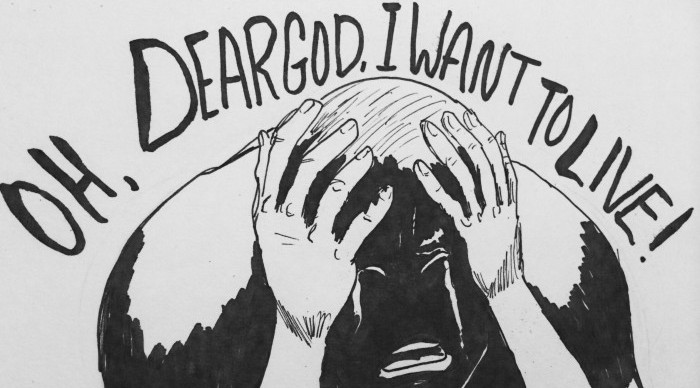

Cartoon by Mariana Hernandez/Staff.

“I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.”

Those were Eric Garner’s last words, uttered in vain as a trained police officer choked him to death on July 17, 2014. Those are the words uttered by protestors in New York, Oakland, Atlanta and all across the nation as our justice system has once again failed to offer even the chance of justice to a black man murdered by the police.

The grand jury decision not to indict officer Daniel Pantoleo is outrageous. A homicide indictment requires evidence of a homicide. But apparently, a video of the homicide isn’t evidence enough.

The New York Police Department has a policy against the use of the chokehold, which is what Pantoleo used on Garner. The police waited seven minutes before trying to give Garner CPR. The coroner ruled Garner’s death a homicide. But apparently, all this isn’t evidence enough.

One frustrating aspect of this case is that it solved some of the ambiguities of the Mike Brown case. The conflicting eyewitness testimonies that threw doubt on the events become inconsequential when there’s actual footage of the events; that footage, however, becomes inconsequential when it is basically ignored.

It seems to me, at this point, that no amount of evidence would be enough evidence. That’s because the problem clearly isn’t with the amount of evidence at all, but the color of the victim involved.

Some people may believe institutional racism doesn’t exist. Some people may believe white privilege doesn’t exist. Those people are wrong, and cases such as these prove that.

Personally, I’ve always been aware of racism, yet that awareness was vague until recently. I had knowledge of racism, in its various forms, yet for a long time it never really sunk in with me. I was fortunate enough to grow up in a diverse environment, with friends and teachers from all types of backgrounds. I never really felt the effects of racism, and I thought, perhaps naively, that the situation of others mirrored my own. I thought that racism existed, but it was on the verge of disappearing.

I was wrong, and recently, I have come to know that. I’ve learned that the experiences of most black people didn’t mirror mine. In fact, it’s far more uncommon, unfortunately, for black people to live like me, almost isolated from the effects of racism, than to have experienced racism first hand.

Though I was fortunate enough to live without being treated unfairly by police; though I was fortunate enough to have been given many opportunities to advance, whether it be in school, in organizations or finding jobs; though I was fortunate enough to have been judged by others by the content of my character and not the color of my skin, most others have not been so lucky. I’ve learned that over the years, and recent events have shown it to me further. Racism is not dead by far.

What’s more troubling to me is that there doesn’t seem to be a solution to the problem – that racism is so ingrained into our society and our institutions, and there is no clear way to rid it from our country. Protests are only a start; they call attention to a problem, and show that people are aware and in solidarity against that problem, but they don’t fix the problem.

So if protests won’t work, how do you fix the problem? How do you fix a country where white men with criminal records are more likely to be hired than black men without records? How do you fix a country where black people are less than 15 percent of the population but make up 40 percent of the prison population? How do you fix a country where police officers can kill unarmed black people and not even stand trial for it? How do you fix a country where black people are treated by the law and by those who enforce it as second-class citizens?

Racism is embedded in our culture and our institutions, into the very fabric this country is made of; it was even built on racism, in fact. I’m not sure it can be fixed.

Nathyia Watson is a College freshman from Buffalo, New York

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.

Do the same thing that Asians did. They were slaves too and built railroads and got paid next to nothing. With next to no help from the government, no affirmative action, no nothing, they were able to become some of the smartest, richest and most educated people in America. Same with Indians who were discriminated against and called terrorists. If they can consistently better themselves and eventually reach a point where they don’t take shit anymore, so can black people.

Stop blaming everyone and start bettering your community from within. Make education the way out of a bad neighbourhood and not drug dealing. Stop making it seem like everyone can get rich by becoming a rapper. If the self-fulling prophecy from the black community goes away, you will stop being discriminated against. It won’t come from an external force, it has to come from within.