The University will provide private, need-based aid to undocumented students, starting with the Class of 2019, University President James W. Wagner announced at a Tuesday meeting with the student advocacy group for undocumented students Freedom at Emory University.

“As a private institution, Emory will use private, non-governmental resources to offer university scholarship support to these qualified students, beginning with the class entering this fall,” Wagner wrote in a statement to the Wheel.

Emory students who are in need of financial aid and are exempt from deportation according to the 2012 federal immigration policy Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) will receive private aid, according to Wagner.

The DACA policy allows undocumented immigrants who were under age 31 on June 15, 2012, who came to the U.S. before their 16th birthdays or have a high school or higher education, among other qualifications, to remain in the country for two years, after which they may apply for DACA renewal.

Wagner’s announcement followed meetings between the Freedom at Emory members and administrators for the past three months as part of the student group’s campaign to help students without U.S. citizenship afford an Emory education.

Although the final details about funding and feasibility have yet to be clarified, Freedom at Emory members have lauded the decision.

Freedom at Emory Co-Founder and College senior Andy Kim, who attended Tuesday’s meeting, said the group was “extremely excited” to hear Wagner’s proposal.

“I’m really proud to go to a school that’s stepping up and supporting a group of people that [have] historically and systematically been oppressed,” Kim said. He also noted the importance of such a policy in the state of Georgia, where undocumented students are not only ineligible for federal aid, but also cannot apply to schools within the state’s University System and cannot pay in-state tuition, which is generally lower than that of a private school like Emory.

The University System of Georgia Policy 4.1.6, which the Board of Regents implemented in 2011, states that a person who is not lawfully present in the United States is barred from admission at colleges within the Georgia System, including the state’s top five public schools. In the same year, the Board also implemented Policy 4.3.4, which prevents undocumented students from applying for in-state tuition.

Emory has shifted its policy despite many administrators’ warnings that finding need-based aid in time for the arrival of the incoming Class of 2019 would be far from possible.

After meeting with Freedom at Emory students on Feb. 18, Wagner wrote in an email to the Wheel that “time is short, considering where we are in the admissions and financial cycle,” in regards to whether the University could provide need-based aid for undocumented students accepted to the Class of 2019.

Provost and Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs Claire Sterk expressed to the Wheel similar worries that the goal was out of the administration’s reach after a similar meeting on March 11.

The advocacy group’s next step, according to Kim, is to continue working with Campus Life leaders to create a welcoming environment for undocumented students arriving in the fall.

“We’re definitely going to still be involved,” Kim said. “Considering the past, we’re excited to begin the process of … making sure that undocumented students feel comfortable on campus.”

While the student activists have already met with Senior Vice President and Dean of Campus Life Ajay Nair on March 3 to discuss potential campus programs that would help undocumented students find jobs and adjust to college life, they will continue these talks in more detail, according to Freedom at Emory members.

In addition to Campus Life officials, Wagner recommended that the group meet with Director of Financial Aid John Leach “to continue the conversation about financial aid,” according to Freedom at Emory member and College junior Nowmee Shehab. Specifically, she added, the group and the administration must figure out how these funds will be sustainable and whether they’ll meet the full needs of the undocumented students.

Both Kim and Julianna Joss, Freedom at Emory co-founder and College sophomore, stressed that their advocacy efforts did not start at Emory.

High school students and graduates at the Georgia-based undocumented student advocacy organization Freedom University, which offers leadership training and college-level classes for undocumented students, along with the school’s Executive Director Laura Emiko Soltis “have been integral in driving this initiative,” according to Joss.

Soltis said she was “so excited I don’t even have the words.”

“It’s just an honor to watch these students mobilize across differences in documentation status and racial backgrounds,” she said, adding that she plans to continue working with other undocumented student ally groups at schools like Georgia State University and Kennesaw State University to continue combating the Board of Regents’ rules barring undocumented students from attending schools in the University System of Georgia and from qualifying for in-state tuition.

Like Joss, Kim also emphasized the importance of the Freedom University students’ advocacy work.

“We want to fully recognize that it wasn’t fully the work of Emory students,” he said. “It’s three years of work of undocumented students.”

What “sparked” the group’s efforts two years ago, Kim said, was a panel featuring undocumented student speakers during Martin Luther King Jr. Week at the Chase Gallery in Emory’s Schwartz Center for Performing Arts. Two undocumented students, Soltis and Emory Associate Professor of African American Studies Carol Anderson discussed the similarities between the undocumented students movement and the Civil Rights Movement as part of this year’s King Week on Jan. 22.

“It’s really inspiring to see how many people can come together on an issue that doesn’t directly affect all of us,” Kim said of the administration’s help this spring. “I’m really glad Emory has taken a step in the right direction, and I hope Emory continues to challenge itself in ways like this in the future.”

As for schools taking similar steps toward inclusion of undocumented students, Soltis listed Berea College, the first interracial and coeducational college in the South, in Kentucky and the historically-black Tougaloo College in Mississippi as southern schools that openly accept undocumented students and offer them need-based aid.

She added that the two schools are “rather small,” and that most universities’ tendencies to not clarify their undocumented student policies can make the application process a daunting one for high school seniors without citizenship.

“It really means a lot for Emory as an ethical leader in the South,” Soltis said.

Valentina Garcia, an undocumented high school graduate and Freedom University member who applied to Emory and has decided to attend Dartmouth College this fall, wrote in an email to the Wheel that she “felt a huge sense of relief” upon hearing the news. She added that Wagner’s decision opened a door for her 15-year-old brother, another member of Freedom University, who plans on going to college right after he graduates.

“I think this decision is an amazing win for the undocumented student movement,” she wrote. “It shows … that this makes Emory a trendsetter for education equality along the South.”

College sophomore Crystal McBrown said she was surprised that the decision came so soon and emphasized the announcement’s reach.

“A lot of [undocumented students] have been here for a while — they went to elementary school here [in the United States], they went to middle school and high school here, then they find out they can’t even afford [to go to college],” she said, “I definitely think this is important for Emory. I’m really proud.”

— By Lydia O’Neal

Correction (4/3 at 10:47 a.m.): Paragraph 17 incorrectly stated that Freedom University Executive Director Laura Emiko Solitis works with student groups for undocumented student advocacy at the University of Georgia and the Georgia Institute of Technology. There are no such advocacy groups at those schools.

Correction (4/3 at 10:54 a.m.): In paragraph 17, Soltis was quoted as saying that she was working with schools in Georgia to pursue policies similar to Emory’s. This is incorrect, as the schools mentioned are public and therefore cannot have similar financial aid policies.

A College senior studying economics and French, Lydia O’Neal has written for The Morning Call, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Consumer Reports Magazine and USA Today College. She began writing for the News section during her freshman year and began illustrating for the Wheel in the spring of her junior year. Lydia is studying in Paris for the fall 2015 semester.

Undocumented students? Or illegal immigrants.

A drug dealer is just an undocumented pharmacist.

Because a lot of those students did not choose to come here and they are smarter you. Because your comment is so ignorant.

Ignorant? Is that what you base your argument on? Their parents could have chosen to come here legally. U.S. law provides them a visa and an avenue to obtain a greencard. So they have options to not be considered “undocumented.” It’s not the immigrant I’m against, it’s the “undocumented.”

1. No they couldn’t have chosen to come here legally. Do you really think that if that was a possible choice anyone would choose to live their life under fear of deportation? The reason people come here as undocumented is because they want to get out of their countries. Primarily in Latin America, they want to leave the dangerous situations of drug cartels. These drug cartels primarily have power because they import drugs to the United States thanks to our “war on drugs” and they also get funded by US policies. So yes, ignorant. Do your research.

Also this is talking about their parents, since a child can’t really say no when their parents move. So the children benefiting from this really did not have a choice.

Additionally any legal pathway to come to the US is currently on a severe backlog due to quotas. These quotas are primarily in place to limit the number of immigrants from specific countries which are fueled by racism. Because, you know, it makes so much sense that the “land of the free” that was founded (read: taken away by killing Native Americans) by immigrants should limit how many immigrants come from specific countries.

2. OH WOW YOU PAY TAXES, GOOD FOR YOU. So do they. And I’m not just talking about sales taxes, which make up the majority of taxes, but also there are a tremendous number of immigrants that file with the IRS (yes you can file without an SSN, its called a Taxpayer ID Number).

3. You really don’t know how University funds work do you? There are certain endowments that are used for financial aid that would pay for this. Your money does not.

4. Emory has accepted and given financial aid to undocumented students for years now. This is just now an official policy that puts it in writing. So honestly, this changes your Emory experience in no way.

You believe that opinions of this institution aren’t going to change but facts are based on this thread they already have and not in a positive way. Legal parents have saved for many years to put their kids through college and help them out and many of the funds these schools are using are those exact funds legal students have paid and continue to pay. If the enrollment drops at this location you can bet funding to undocumented students will come to a screaming halt. No money from the legals, no money for illegals. It is the responsibility to support the people that are here legally before we continue to give handouts to those that shouldn’t be here.

I say to every student thinking about spending even one dime to attend this school, find one that uses your money wisely, On you!!! And not one that thinks it is ok to give to those that should not be in this country. If your not supporting this cause no one will because there are zero government funds allowed to this stupid policy.

Yes because a bunch of anonymous (4?) people commenting on a school newspaper is far greater than the (tens? hundreds?) of those praising the school’s decision un-anonymously on social media. The majority current students and staff. That totally means people are seeing this as negative. You’re so right. You beat me.

James a few responses to your personal comments are merely a drop in the bucket. I was referring to the staggering 84% of the legal population, (at current poles in Feb. 2015) against the free pass on criminal behavior of illegal aliens. And yes that is about those criminals that broke into this country and have been using the resources and taking jobs from hard working Americans when they have zero right to be here and that should include their anchor babies or the ones they brought here as babies. The American public is speaking loud and clear and they are against giving any freedoms to these people or their children. If paying students stop attending this school it would forced to stop giving away free educations to them or forced to shut their doors. The government will not allow funds they pay to go toward these people so it is up to students to stop attending. And a couple hundred illegals stating how they love this policy is just that, A couple illegals that have ZERO rights anyway and shouldn’t have to be heard at all unless they are back in Mexico screaming across the one true country. MEXICO!!!

Where are these numbers coming from? 84% staggering? Because last time I checked (this morning):

http://www.pollingreport.com/immigration.htm

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2014/07/02/immigration-reform-is-super-popular-heres-why-congress-isnt-listening/

http://www.gallup.com/poll/160307/americans-widely-support-immigration-reform-proposals.aspx

And this is what I get when I google the phrase “number of americans who approve of immigration reform”. So actually no, the majority of Americans are not on your racist side. Where are the majority of Americans speaking? Anonymously in comments because they don’t exist.

Paying students are not gonna stop attending this school. Also the people who are saying how much they love that policy are LEGAL students. Check it out, check out the likes and comments. They are all campus leaders and students from all races and background and most if not all LEGAL.

https://www.facebook.com/emorywheel?fref=ts

You just have to scroll down and find the link to article and see who likes it (if you are a current student then youd recognize most of the people. I’m assuming you’re not a stranger who has no business commenting on a school newspaper with no relation to a PRIVATE institution)

Lastly, yes, I said racist. You are racist. All undocumented immigrants are not Mexican. 1. Mexico is not the only country in Latin America and 2. There are a large number of undocumented immigrants from Europe and Asia.

Wow James, you are so smart and so dumb. I’m not shocked you are a student at this school and support this position.

Do yourself and the world a favor and take the time to read anything before you reference it. Or did you not learn this at school yet. Must not be educated at all with your paid for education going to illegals. All three of your references are completely out of date. I know you probably had a difficult time reading anything you cannot comprehend so let me help you out.

Gallop Poll taken Jan 30, 2013- more then two years have passed since

Washington Poll taken July 2, 2014-more than 9 months have passed

Polling Report taken March 21, 2014 -more then a year has passed.

But you are correct rocket scientist- polls take so long ago are still relevant. Facts are that things changed and because of your lack of intellect you will have to do your own research to find the most current numbers which were posted in FEBRUARY 2015.

You call me a racist because I don’t want a bunch of illegals here. I could careless what race they are. They are illegals and do not belong here. CRIMINALS and should be locked up for there crimes against this country, not rewarded. And incase you missed the boat, wait I know you already did) 57% of all illegals are from MEXICO. So my statement is more factual than not, whereas your statements are outdated and lack knowledge.

Most of these comments you have no clue who they are from. Did you get a student/faculty roster to cross check the names with the legal. Wait, don’t answer, I don’t want you to show you aren’t that bright. The fact is that those holding those signs are mostly illegal and should go and those of us that don’t believe they should be here or get a free pass with this school will continue to make it our work to put an end to it. And yes there are zero recommendations from any of us for this school.

So next time you use the word racist you should know its definition. I am far from racist and wanting a bunch of illegal CRIMINALS to be sent packing and get no benefits from my hard earned tax dollars does NOT make me or any of us racist. EDUCATION is the Key to your success, since you are obviously not getting it here you should move on to a community college where they like the special kind of student you are.

So to summarize:

1. You still haven’t given me a source to back your claim. Also you said “staggering 84%”. From my education, I learned what staggering meant. If the numbers changed dramatically in 9 months, that’s not staggering. PS http://publicreligion.org/research/2015/02/survey-roughly-three-quarters-favor-substance-behind-obamas-immigration-reform/#.VSaD-BPF9Vs

2. You didn’t answer my question. Do you have any relation to this school? Or are you just sour because undocumented immigrants who study hard can get in and you can’t?

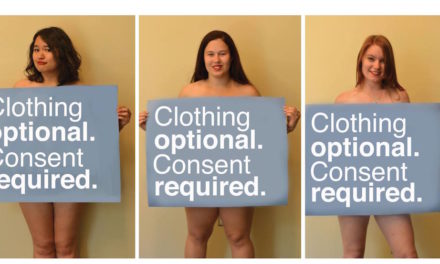

3. I do know who most of these comments are from: SGA representatives, student leaders, etc. I know because I know them personally since I recently graduated. Most of the people in the photo up here (basically anyone second row and up) is an Emory student. I know because I was there.

4. This is my last comment. I’m gonna go enjoy the Emory degree I got and make lots of money at the job that degree got me.

Like I said, do the research yourself. I presume since you are an Emory graduate that is why you are unable to complete the task.

I wouldn’t have ever lowered my standards to attend a half rate school like Emory. My degree is Ivy league. You know the one that Emory students get arrested for trying to break in. I’m sure you wont be able to figure this one out either since you are in fact a Emory graduate.

You don’t have to go to Emory to know what this school is doing shouldn’t be done.

And yes they are many students on those steps that attend that school. Notice how the majority of them are probably illegal as well. (Yes I know, I’m a racist). Only because you do not know how to define a word properly since you attended Emory.

Oh and let me know forget, Emory has a 28% acceptance rate. My school has a 7% entry rate. Seems more people with their free educatio0n program’s can get into your school than my Ivy league school you would have had no fighting chance.

And why is it important to me since I didn’t or would never have chosen this school? I’ll answer this just because the world doesn’t evolve around some half brain that only recently graduated school and probably spent 6 years doing it. My firm is fighting immigration reform every single day and we fight every cause that comes up, not just the ones some half twit thinks we should. You can bet we are creating profiles as we speak to prevent any further government funding from being given to this school and as with previous attempts to rape the American tax payers we will put an end to it. The laws are not on the side of illegal criminals and neither are true Americans

‘they are smarter than you’ as you know who is smart as who is not? I’m an immigrant from Africa and I came here legally… Please get out with your pedantic comment.

I’m also an immigrant from Haiti, what are you talking about? Illegal or undocumented, we all deserve an educaction.

I understand the gesture. But why is more funding not given to documented students who still need are not getting sufficient funding?

As an Emory student this is outrageous. How about the parents who have saved up money through their hard work for their children’s college education. I work 2 jobs and attend full-time and still barely make it work. You don’t think the “private” cost isn’t going to effect other costs on campus? I’m a taxpayer! The benefits I receive are due to me being one. How about fixing campus housing for low income students?

This is absurd. There was a time when being in a country illegally meant you kept your head low and tried to AVOID being noticed. Now, not only do we allow illegals to stay in this country, but they have the nerve to stand up, protest, and demand that we give them MORE money. Whatever happened to the law? We have laws against illegal immigration, but we have laws preventing us from shipping illegals back. Which is it? “Undocumented and Unafraid”? Let’s bring back “Illegal and Hiding”!

Also, what is with calling them “undocumented”? They can get drivers licenses. They can enroll in schools. They can get treated at the hospital. We have PLENTY of documentation on them. If they are going to qualify for this assistance, they have to be DOCUMENTED that they are here ILLEGALLY!.