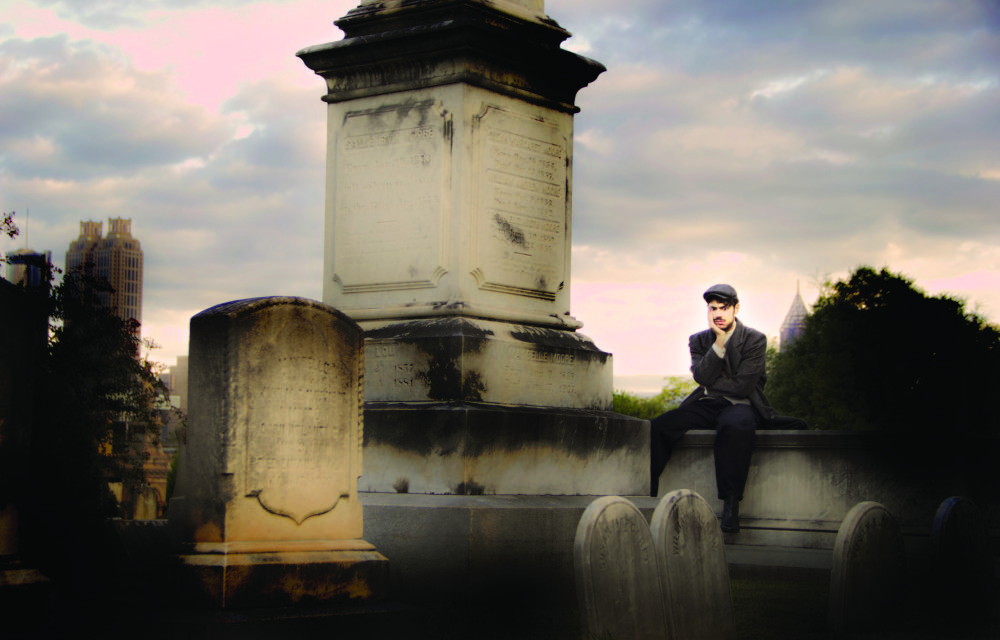

Jake Krakovsky (C’14) in costume as Yankl, the protagonist of his work Yankl on the Moon. The play explores the consequences of the Holocaust on the Jewish psyche through humor. | Courtesy of Egan Marie

It’s hard to take your eyes off of Jake Krakovsky.

The Emory University alumnus (‘14C) sits on top of a wooden barrel, a large book in his hand; he is quiet, innocuous even.

However, the moment the show begins, Krakovsky’s vibrance springs to life as he fully becomes each character in his one-man show, “Yankl on the Moon,” telling the stories of villagers of Chelm.

“Yankl on the Moon” began as Krakovsky’s senior honors thesis at Emory University.

The show explores the tragedy of the Holocaust through the comedic stories of the clownish villagers of Chelm, a mythical town traditionally used in Jewish folktales.

The independent production opened on Feb. 12 in the Alliance Theatre’s Black Box space at 8 p.m. and will continue its run on Feb. 19 at 10 p.m. and Feb. 20-22 at 8 p.m..

Producer and Emory alum Emily Kleypas (‘13B) introduced the show, telling the audience that “more people need to hear these stories.”

Krakovsky’s main character, Yankl the hogwatch, tells stories about the villagers, from the village schmuck and the village cobbler to the three rabbis of Chelm.

Krakovsky began transitioning from character to character immediately. Though initially a bit difficult to remember the name and role of each character with all of his transitions, he attempted to use both his body and his voice to distinguish between the characters.

Thanks to his training at Accademia dell’Arte in the style of Italian street theater, portraying multiple characters using physicality and vocal shifts seemed natural for Krakovsky. After the first few scenes, it became easier to keep track of each significant character.

In a piece about the Holocaust, the amount of humor was entirely unexpected.

The audience seemed unsure about whether or not they could laugh at the first comedic moments in the play, despite the fact that they were clearly meant to be humorous — the characters were so absurd that it almost felt inappropriate to laugh; after all, this was supposed to be a play about a major tragedy.

Soon, however, everyone realized that the piece was going to be in the style of such over-the-top humor and began comfortably laughing at the clownish nature of the villagers.

Perhaps this was Krakovsky’s greatest accomplishment: though the topic of the Holocaust has been tackled from a comedic standpoint in other works, his style and delivery made it impossible to find offense or to remain serious for long.

Krakovsky cited an Emory class with Professor Deborah Lipstadt on the history of the Holocaust as part of the reason why he chose to use comedy for his work.

He noticed how much humor she brought into the class and realized that he was, for some reason, no longer being affected by most of the material.

Krakovsky wondered if the reason for this was his own desensitization to the material, because being raised Jewish meant learning about the tragedy from an incredibly young age — it was something that was always there in his life from the outset.

Whatever the reason, he knew that he needed to approach the Holocaust from an angle that was different from the style of the documentaries and fictionalized movies of the previous generation.

“Comedy serves to open [the audience] up and allow the tragedy to come in in a more pure form,” Krakovsky explained. “For the third generation [of Holocaust survivors], the Holocaust is inescapable, I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know about the Holocaust, and so [documentaries and movies] weren’t working anymore, and comedy has always been my way into everything. So, I’m gonna come at the Holocaust through comedy.”

His plan worked.

Easily the most powerful moment was Yankl’s reflections on the Holocaust in his conversation with the Angel of Death: it was not millions of murders, but “one murder, six million times.”

Though Yankl, in all of his comedy and humor, had moments of seriousness in the play, Krakovsky’s sudden transition from humorous and naive to complete dismay elicited an empathy from the audience that was more intense than that from previous poignant moments presented in the play.

Instead of talking about the Holocaust for 67 minutes, Krakovsky simply told the stories of the people: he brought them to life, made them real and, ultimately, kept them alive through their stories.

He infused the play with Jewish elements, though references to the Torah were unplanned in the writing process.

“I was writing from the perspective of a Chelmsman,” Krakovsky shared. “What type of bank of imagery they would be pulling from — of course, a Jewish one, so the show is riddled with Jewish imagery. It helps build a universe.”

Despite running around the stage for the entirety of the play, he credited his team with the success of the piece.

“This would not exist at all if it weren’t for the the incredible dedicated patient, inspired artists with whom I am so lucky to be surrounded by,” Krakovsky said.

Krakovsky shared that he realized that he had something special in a performance of a version of the play at Emory’s Burlington Road Building in April 2014.

People came up to him and told him that the story was important, and he listened, bringing it to its next stage at the Alliance Theatre.

“It is a play about the Holocaust, certainly,” Krakovsky said. “It is a play about heritage and the legacy of trauma, but it’s also a play in service of ‘tikkun olam,’ [a central tenet of Judaism], which means ‘to heal the world.’”

Krakovsky hopes to take the play on the road, to share it with those in high schools, colleges, community centers, synagogues and anyone who will listen.

“I really believe in it,” Krakovsky said. “I don’t know if I’ve ever made something before where I believe in this so much that I want to show it to as many people as humanly possible.”

While the metaphor of “Yankl on the Moon” represents Krakovsky’s personal distance from the Holocaust as a member of the third generation (his grandfather is a Holocaust survivor), he deals with his conflict in the same way as Yankl: by telling stories.

His “tragi-comedy” is hilarious, poignant at times and a remarkable illustration of the power of stories.

“It’s a play about how comedy can be a force for healing and transformation,” Krakovsky concluded passionately. “It’s a play about how storytelling can heal the world.”

– By Julia Munslow, Staff Writer

This article was updated at 2:52 p.m. on Feb. 18, 2015 to reflect the insertion of the word “independent” in the sixth paragraph, to change “Alliance Theater” to “Alliance Theatre,” to change the misused word “schmutz” to “schmuck,” to clarify “references to the Torah” in the paragraph about the play’s Jewish elements and to change various attributions to “said” and to clarify that not all of Krakovsky’s team are Emory alumni.

julia.munslow@emory.edu | Julia Munslow (18C) is from Coventry, R.I., majoring in English and creative writing. She joined the Wheel’s Board of Editors her freshman year as assistant arts & entertainment editor and served most recently as executive editor. This past summer, she covered national politics for Yahoo News. Her photos of the 2016 Trump chalkings protest won an SPJ Mark of Excellence for Breaking News Photography and were syndicated by national media organizations including The New York Times and Newsweek. In addition to the Wheel, she is an Interdisciplinary Exploration and Scholarship (IDEAS) Fellow, a member of Mortar Board and a member of Omicron Delta Kappa.