In 1983 Alfred Smith and Galen Black were fired from their jobs after testing positive for mescaline, the main compound in the illegal and hallucinogenic peyote cactus. As members of the Native American Church, they had not ingested peyote for recreational but rather for sacramental purposes. So they sued, and the case was brought to the Supreme Court in 1990, where their claim to religious freedom was denied by a six-judge majority.

Nationwide outrage at the ruling ensued, and the decade-long issue was finally resolved three years later when a coalition of civil liberties and religious groups successfully lobbied Congress to pass the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993, a non-controversial piece of legislation that states, “Government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability.” The only exception is that the government may burden such a person “in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest.” In other words, the government must turn a blind eye toward illegal yet benign religious practices but maintain the authority to prohibit religious practices that might cause societal harm, such as human sacrifice, to cite the most extreme example.

Now, 21 states have passed their own versions of the Federal RFRA, most recently Indiana, whose governor Mike Pence signed the Indiana RFRA into law last Thursday. And the controversy is rampant because there is one key distinction between the Federal and the Indiana RFRA.

While the Federal RFRA does not define what constitutes a “person,” the Indiana RFRA in Section 7 defines a person as an individual, a religious organization or a limited liability company. In other words, a corporation. Therein lies the controversy, for it extends the protections of the RFRA to businesses. And the only way a business could benefit from RFRA protection is if it is being sued for either not serving or not hiring somebody, because doing so would infringe upon the religious beliefs of the business owner. It thus comes as no surprise that liberals and members of the Lesbian, Gay, Transgender and Bisexual (LGBT) community are outraged at these state RFRA bills that have been popping up recently.

Right now, Pence is trying to clarify that the Indiana RFRA does not allow businesses to deny service to anybody. But if the RFRA is revised to include such an anti-discrimination clause, then there will have been no point in passing it in the first place. Because the only people who support the Indiana RFRA are those who hold prejudices and seek to legitimize their will to discriminate others in the eyes of the law.

On Monday, Senator Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) voiced his support for the Indiana RFRA on Fox News. In response to the widely expressed concern that the RFRA would make legal the denial of service to gay or lesbian couples seeking wedding arrangements, he said, “The issue we’re talking about here is should someone who provides a professional service be punished by the law because they refused to provide that professional service to a ceremony that they believe is in violation of their faith?” Then, delivering probably the biggest non sequitur in national politics all week, he added, “I think people have a right to live out their religious faith in their own lives.”

Nobody is disputing people’s right to live out their religious faith in their own personal lives.

To quote Tom Hagen from Francis Ford Coppola’s mafia classic “The Godfather,” “This is business, not personal.” To conflate the two is a feeble attempt to mask prejudice with religious freedom. It is the claim by RFRA supporters that people have a right to live out their religious faith when conducting business that is the problem. Businesses do not have the right to discriminate on religious grounds.

What’s really going on is certain business owners do not want to have to interact with LGBT people, period. And to ask for a law that limits the physical freedoms of others so that they might have a freedom of conscience is absurd.

Refusing to serve somebody based on their beliefs or sexual orientation is not religious freedom. Let these business owners not make society think that they are in need of a law that, under the guise of guaranteeing this already existing freedom, prevents them from being sued for discrimination.

Supporters of the RFRA are anti-American in the sense that they seek validity in the pursuit of closing their circles out against the LGBT community. They are also anti-capitalist, which might come as a surprise to them, because they are also uneducated on the economic policies they espouse.

They are wholly incapable of seeing beyond their ignorance that they are in fact advocating for market failure. Businesses that refuse to sell to willing customers are, fundamentally, aberrating from the free market. They are throwing in the towel in the competition between businesses to make the most profit. While they might not have to serve members of the LGBT community, most other businesses will continue to do so. Not to mention they will lose potential straight customers who are in general turned off by such intolerance. As a result of this decreased demand, they will have to raise prices just to make ends meet. They will be at the mercy of patrons who find it worthwhile to pay a premium to be served by a business whose values align with their own. Their moral bankruptcy will translate to actual bankruptcy.

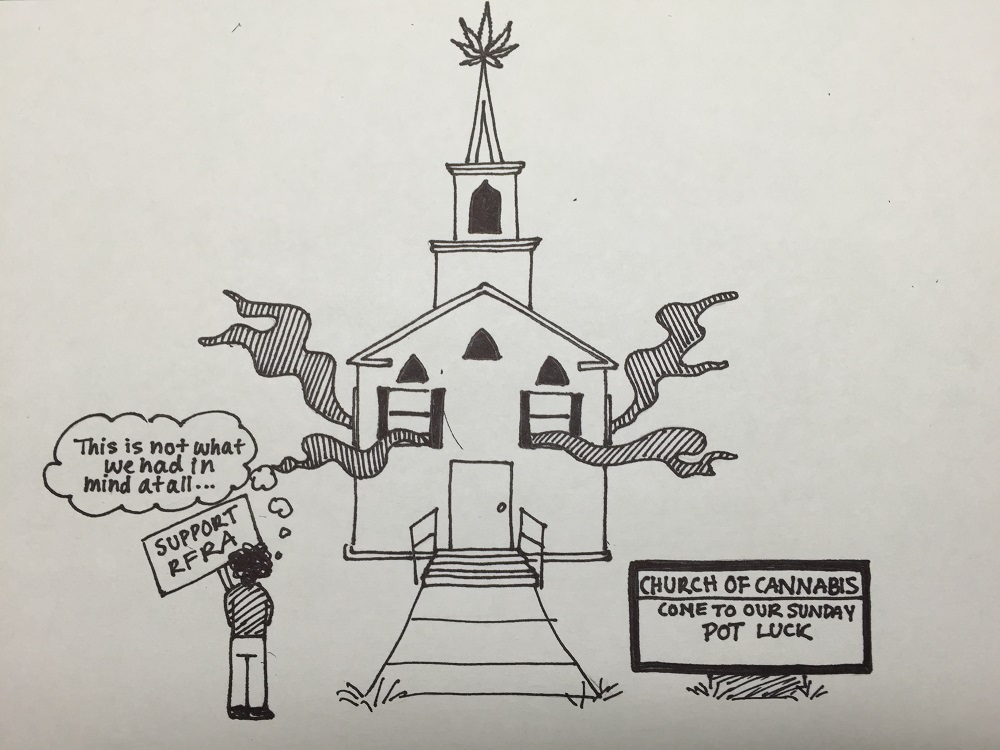

In pursuit of what they interpret as the right to exercise their religious freedom, supporters of the RFRA have essentially delegitimized their own identities as intelligent, patriotic business people. In their failure to recognize the humanity of one community, they have dehumanized themselves. We might call this whole fiasco a zero-sum game were it not for one thing that happened last week as a result of the passing of the RFRA: the establishment of the Church of Cannabis.

“This is a church to show a proper way of life, a loving way to live life,” said Bill Levin, the Church’s founder. “We are called ‘cannataerians.’”

Levin is strongly opposed to the Indiana RFRA. But he has decided to take advantage of the legal loopholes that it has opened up.

Levin also says that the Church will set up counseling for heroin abuse “since we have a huge epidemic in this country. We’ll probably have Alcoholics Anonymous, too.”

The Church of Cannabis attests to the notion that out of tremendous human weakness can come some good. I cannot help but notice the immense irony in the Federal RFRA having begun with two peyote eaters going to church and the Indiana RFRA ending with a pot smoker founding his own church. These three individuals are trailblazers of religious freedom as demonstrated by their willingness to play with the fires of legality. They, not the pro-RFRA business owners of America, are the bulwark against the adverse consequences of strict adherence to secular laws.

Editorials Editor Erik Alexander is a College junior from Alpharetta, Georgia.

Erik Alexander is a College senior majoring in economics.