At the end of last semester, I had what could only be called one of the highlights of my culinary experience. My friend, her family and I all went to a local authentic Chinese restaurant, owned and operated by Chinese immigrants using traditional recipes that served what could only be described as the best food I have ever tasted. Upon arriving back on campus, I told one of my other friends about this amazing restaurant to which we had to go. My delight was immediately put down by a response that implied I should not go back to that restaurant unless I was accompanied by a friend of Chinese descent. Shocked, I stared back in silence as I was told that to go back unaccompanied would be to be invading a space meant for a group of which I was not a member. How does a member of one cultural group cross the invisible divide and experience another culture without appearing to appropriate the other culture? I think the answer to this question starts in almost every elementary history class in the United States.

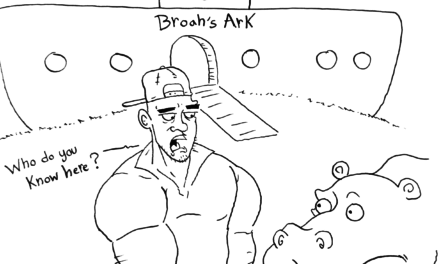

If you spent the greater part of your childhood being educated in the American school system, or simply watched “School House Rock” as a child, you probably heard of “the great American melting pot,” a concept that asks the student to think of American culture as a genuine combination of cultures that makes up one, collective culture, a concept that isn’t reality. In fact, to truly be a melting pot of cultures, every culture would be appropriated into the existing one, making the difference between cultures indistinguishable and the issue of my patronage to any restaurant a non-issue. Rather than thinking of the United States as a melting pot, I prefer to think of it as a buffet.

After pondering the incident with my friend for quite some time, I began to see where my friend was coming from. I can respect and understand how people of different cultural backgrounds would enjoy having establishments to frequent that are culturally familiar and how, if those establishments were frequented by members of different cultural groups, they would no longer retain their same character. After all, culture binds people together in a way that is hard to describe. It is comforting to spend time with people who understand and inhabit your same culture. Humans, by nature, seek out what is familiar, thus necessitating the existence of places where one can be completely immersed in a culture and allowing many businesses to thrive. This idea is rarely mentioned in the educational system, a disservice to students who, like me, were left in the dark about the possibility of offending someone simply by eating a meal.

Recent months have brought the issue of cultural appropriation to light again and many are producing articles instructing members of the “majority cultural background” on how to respectfully appreciate another culture without appropriating it. What exactly does it mean to be a member of the “majority culture?” What I think people are trying to convey is the idea of a culture that the majority of people feel comfortable experiencing rather than a “majority culture.” Every family has their own traditions and every region has variations on customs that render them as unrecognizable to members outside of that region as some of the types of food were unrecognizable to me in the Chinese restaurant, yet in most instances, an inhabitant of a different region would not feel uncomfortable in the new variation, just surprised. This is the concept which I think many take to mean “majority culture.”

As a Midwestern female of Northern European ancestry, I identify as an American first and foremost, the most stereotypical member of the “majority culture” yet I spend an inordinate amount of time immersed in a culture that I don’t identify as “mine.” As an Irish dancer, I have been exposed to Irish culture and customs, and while my extended family claims decent from Ireland, I do not identify as Irish. This presents an interesting dynamic as those around me at dance competitions speak in Gaelic and practice traditional Irish customs and, in turn, I follow their lead. Am I appropriating Irish culture as I dress, dance and perform their customs or am I merely appreciating the culture that was brought to me by the “melting pot” of this country? Personally, I feel as though I am doing neither, at least not completely. I have been accepted into this Irish culture, not at birth like most, but later in life. This makes my cultural membership a choice, both on my part and on the part of other members of the Irish culture. Similar to a diner at a buffet who chooses between beef or chicken, it is his choice as to which meat he picks, but his only options were those put forth to him by the chef, thus we chose which cultures of which we will be a part, and they must in turn be willing to accept us.

My dislike of the “melting pot” description stems from my everyday experiences that have left me with conflicting information on how to respectfully enjoy aspects of cultures that aren’t ancestrally “mine,” but are an equally important part of the society in which I live. Just like a buffet would be bland if it only contained vegetables, so would the U.S. if there were only one cultural option. Each choice in the buffet line adds something unique to the combination and makes it diverse and interesting. It also allows the “diner” to decide for himself with which foods, or cultures, he finds most desirable or comfortable. This choice doesn’t mean that the other options are bad, it merely means that choice is essential to living.

The key to educating students and young members of society about the cultural situation in the U.S. is to describe it not as a fusion but rather a collection. Often times overlooked is the ability of those of us living in the States to sample different cultures on a daily basis. We must emphasize to younger generations that we aren’t the “great American melting pot” – we are the great American buffet. Full of choices and opportunities.

–By Alli Buettner

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.